The malaise of our times is encapsulated and iterated over and over in this year’s Venice Biennale—whether racial conflict, gender redefinition, women’s rights, immigration, environmental threats, or any combination thereof. One begins to wonder, as one wanders through this sprawling extravaganza, whether there has ever been a more troubled era. The answer of course is yes, but the difference is that today our troubles are exposed and available for dialogue.

The Biennale (through Nov. 24) is made up of two parts: one, the main exhibition, which a selected curator organizes from an international slate; two, the national pavilions where countries showcase artists to represent them. Most of this takes place in the Giardini, a park on one end of Venice, and the nearby Arsenale, the former shipbuilding complex.

Venice Biennale Signage. Photo by Scarlet Cheng.

This year some 90 countries are represented in these two venues and, for those not allotted a space there, in hired venues throughout the city. The main exhibition, “May You Live in Interesting Times,” was curated by Ralph Rugoff, longtime director of London’s Hayward Gallery. It’s worth examining that title—its provenance points to the slippery notions of culture that we have become more aware of in the 21st century. It’s a purported “Chinese curse,” oft quoted by British politicians in the 20th century—and even by the likes of Arthur C. Clarke and Robert F. Kennedy—although there really is no corresponding Chinese saying. It’s just another piece of made-up Orientalia, like Fu Manchu. Rugoff himself has deflected all this, insisting in his curatorial statement, “[T]here is no over-arching narrative or thematic umbrella.” However, he has also said that choosing some artists led him to choose others in some kind of simpatico way.

I did find many of his choices very interesting. We do live in interesting times, and the underlying assumption of that phrase is that we live in troubled times. Naturally, those troubles are reflected in art. While the national pavilions and even some choices in the main exhibition include artwork identified with a specific culture/territory, they also reach towards broader issues like cultural memory, environmentalism and boundaries.

Christoph Büchel, Barca Nostra (Our Ship), 2019.

Unfortunately, this reach sometimes goes wrong, as in Swiss-Icelandic artist Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra (Our Ship). His bright idea, approved by someone in the Biennale, was to install the fishing vessel in which over 700 migrants died on their way from Libya to Italy in 2015 after colliding with a Portuguese freighter. For the Biennale, their death ship was hauled to Venice and set up along a well-trod path and across from a café at the Arsenale. At first, in my haste to cover the art, I passed it by, thinking it was another piece of naval detritus—the work was deliberately unmarked. When I learned the identity of this “art piece,” it struck me as cold exploitation of other people’s tragedy and an insult to art.

Martin Puryear, Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute), 2019. Photo by Scarlet Cheng.

Let’s move on to what is good—and there’s a lot that is. The American presence is strong this year. The main exhibition includes 17 American-born artists, plus another nine born outside the U.S. but now living here. The American Pavilion, in a neoclassical building near the entrance of the Giardini, was graced with the work of celebrated sculptor Martin Puryear, who was chosen to represent the U.S. Puryear covered the front of the pavilion with an elegant wooden screen, attached at the back to a curved black tube, in Swallowed Sun (Monstrance and Volute) (all works 2019, except where stated otherwise). Inside the building, several of his sculptures refer to historical personages or objects. For example, A Column for Sally Hemings shows a cast-iron shackle attached to a stake driven into the top of a tall white column, clearly a visual allegory. Hemings was the African-American slave who bore several of Thomas Jefferson’s children.

Martin Puryear, A Column for Sally Hemings, 2019. Photo by Scarlet Cheng.

An American, Arthur Jafa, won the Biennale’s top prize, the Golden Lion, for an artist in the main exhibition. The Los Angeles artist and filmmaker’s 50-minute film, The White Album (2018) explores white supremacy through interviews with white people. (Yes, the title is a riff on Joan Didion’s book.)

Arthur Jafa, The White Album, 2019. Photo by Francesco Galli.

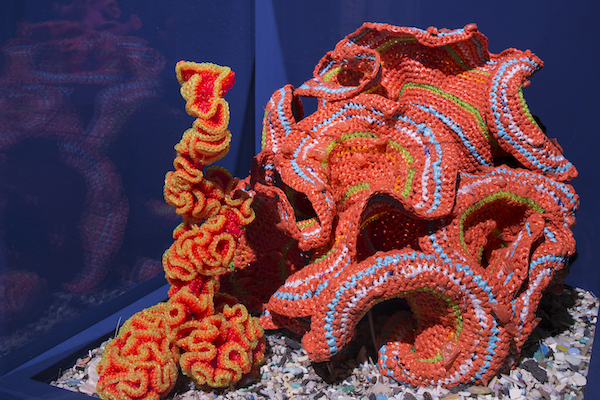

Out of 83 artists in the main exhibition, nine work in Los Angeles. A little over a third of them were born abroad—Njideka Akunyili Crosby in Nigeria, Jill Mulleady in Uruguay, Christine and Margaret Wertheim in Australia. Their work may be a hybrid of cultures—Crosby’s large paintings/collages depict everyday life in the black community, integrating traditional African fabric patterns. Or they may address international issues—the Wertheims and their collaborators have created Crochet Coral Reef out of intricate crocheting, to bring our attention to the destruction of coral reefs the world over as oceans warm and grow increasingly toxic. They’ve been working on this magnum opus since 2005, and it’s instructive, whimsical and quite beautiful.

Margaret Wertheim and Christine Wertheim, Pod Worlds – Beaded, 2005-2016. Photo by Francesco Galli

There are so many phenomenal national pavilions (Lithuania won the Golden Lion for best national pavilion, for a performance piece about global warming), I’ll just mention a handful of the most memorable. Both the Philippines and Indonesia were surprising for elaborate installations that evoked the history of wunderkammern. For Island Weather Filipino Mark Justiniani created three large containers covered with glass, on which visitors are invited to walk after removing their shoes. Below, one sees a dizzying infinity of papers, drawers, meters and specimens in bottles—a trick done with mirrors, but impressive all the same. Indonesian artists Handiwirman Saputra and Syagini Ratna Wulan collaborated to create Lost Verses, a large room filled with dozens of showcases, each marked with a saying and containing miscellaneous items such as a key or a fishing lure. The phrases were clever—“Transformation is an act of re-imagination,” “And eyes were shut, in order to see.” “It’s kind of a game,” Syagini told me. “First you choose one from the front, and that will lead you to others.” The scale of this piece and its underlying playfulness and wit were very impressive.

Installation view of Mark Justiniani, “Island Weather,” for the Philippines Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale, 2019.

Mexico had two strong exhibitions. In its pavilion Pablo Vargas Lugo presented Acts of God, a film that restaged excerpts from the Synoptic Gospels. Jesus and his disciples are brought to gritty, human levels—in the episode where Jesus is supposed to multiply bread to feed a multitude, he’s shown tearing up a loaf and throwing it at others. Two of the most powerful works in the Biennale are by Teresa Margolles, who received a Special Mention award from the jury. In the main exhibition are Muro Ciudad Juárez (2010), made up of concrete blocks topped by barbed wire, and La Búsqueda (2014), a chilling installation. The latter, presented in a darkened room, features three large glass panels on which are pasted tattered posters of women who have gone missing in the drug/border wars. Every so often the room and panels shudder, as the thundering sound of a train rumbles by.

Teresa Margolles, La Búsqueda (2), 2014. Photo by Andrea Avezzù.

As for individual artists in “Interesting Times” I found Anicka Yi’s installation in the Arsenale especially arresting. In Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble), five large cocoon-like pieces dangle from above, flanked by gritty metal columns of the original architecture and old windows and exposed brick. Animatronic moths flutter inside the cocoons. The wall captions assert “associations with bodily fluids, contamination and disease.” However, I hardly think that biomorphic associations are necessarily sickly and contagious. Yi’s visually elegant and haunting work takes wonderful advantage of site.

Anicka Yi, Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble), 2019.

Elsewhere, outside the official venues, I’d like to mention the Heist Gallery pop-up in Palazzo Benzon (only up for a month), “She Persists: 20 Female Voices of Rebellion.” It was refreshing to see such a clear feminist declaration, featuring as it did works by Judy Chicago, The Guerrilla Girls and Shirin Neshat. There was also a hypnotic film by Tonia Arapovic, Indecision IV (2018), featuring Rose McGowan, who’s decided to leave Hollywood and take up the artist’s life instead.