Playfully assaulting the construct of the rational, coherent, autonomous individual in his solo exhibition “You Have Nothing To Worry About,” Andy Fedak’s new stereoscopic (3D) film and virtual reality installation and three early “anxiety” videos explore his intertwined concerns—cognitive systems, the interface between the human organism and technology, and anxiety—as they feed into each other to destabilize a sense of objective reality.

A loosely structured and vaguely dystopian narrative ostensibly about a character who, living at a weight loss camp, senses that his world has shrunk to the boundaries of his room, How to Lose Weight in Seven Easy Steps (2015), a 24-minute film requiring 3D glasses, undermines the reliability of first person point of view and assumptions that the world can be categorized, understood and interpreted rationally. Rather than calling into question the trustworthiness of the narrator by introducing conflicting accounts, Fedak posits that his narrator’s perception is fragmented and incoherent. Indeed, one might wonder if the narrator lives in a padded cell or if his story exists entirely within his own mind. Notes of humor are delivered by his fascination with reality TV, his disappointment with reality when he escapes his room, and his perception that he has found a life-size TV that he can walk into.

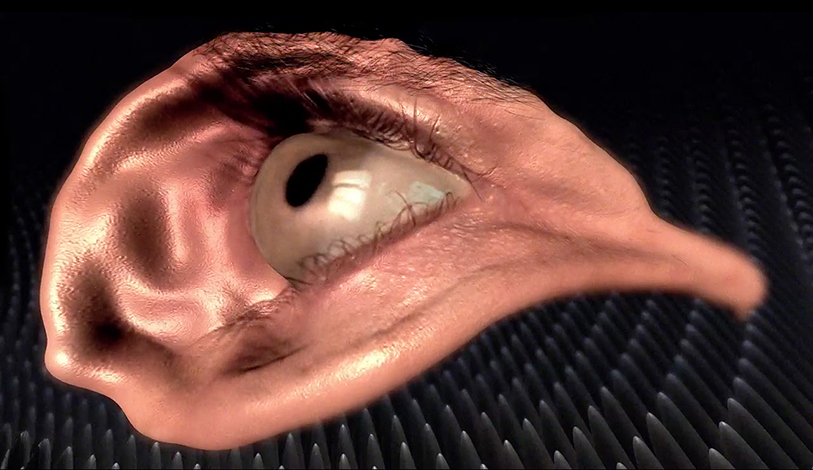

The virtual installation Volumes and Daydreams (2015), which uses proprietary technology developed by a Belgian visual effects company, allows viewers to screen 3D-rendered objects from Fedak’s film and videos with special goggles. Fedak’s digital toolbox is inescapable throughout the show, and it is especially conspicuous here. Like a series of studies, Volumes and Daydreams isolates individual elements that coalesce into a larger whole in his film and videos. More importantly, the work presciently interrogates the limits of human consciousness as it underscores how technology plays an increasingly embedded role in shaping perception, even forming a system of conceptual constraints. These virtual objects—a disembodied eye, a sprawling complex of hybridized organic-mechanical tubes and other biomorphic brain benders—tweak notions of human autonomy and play with the shifting boundaries between biology and technology. The disembodied and seemingly sentient eye perched on some sort of scaffolding may reference the manufacture of human tissue; it resembles a remote sensor disconnected from its central nervous network as it blinks and stares, reinforcing the utter subjectivity of our experience of the world.

Fedak’s early “anxiety” videos—General Anxiety Disorder, Orange County Surreality, Toilet and Office (2006-2009)—feature more hybridized objects with roiling, skin-like industrial surfaces that move and breathe, as if they are embedded at the cellular level with a kind of neural network that supplants the need for autonomous intelligence. They evoke a Kafka-like nightmare, a distortion of reality much like the narrator’s in How to Lose Weight in Seven Easy Steps, except that in the 21st Century, the nightmare is one of morphing into a human-machine rather than a bug. Assertions that our perceptions of the world are unreliable have long been fodder for speculation, and Fedak’s show revels in that point, cavalierly quipping, “You Have Nothing To Worry About.”

0 Comments