At first, Andrew Dadson’s newest exhibition at David Kordansky, “Painting (Organic),” seems to lack cohesion, with medium and mood shifting frequently. There are three very distinct types of works on display: a collection of photographs hung in a grid formation; six large, heavy paintings; and live plants with grow lights trained on them. Despite these differences, however, if one spends time with Dadson’s multivariate works, they begin to yield, sometimes subtly, other times more emphatically, their central theme of the relationship between humans and their natural and manmade environments.

The paintings demand the viewer’s attention first. Their size is matched by the bombastic nature of the paint application. These are no diffident monochromes or coy portraits; they are weighty in their physicality and the somberness of their aura. Like other contemporary painters, such as Mark Bradford and Adrian Ghenie, Dadson loves to build up his material and then scrape and sculpt some of it away, using hand tools or his fingers. The heavy paint, mostly in moody black, isn’t confined to the boundaries of the canvas either; it appears to have oozed off the bottom of the frame and then ossified into something akin to hardened lava.

Evocations of the natural world are indeed rife in these works, with Dadson titling his works Miami Islet, Painting Fall (Organic), and Ocean Wave, among others. One is even named Rose, and with its thick accretions of paint may be a wink at Jay DeFeo’s own Rose. And although the paint is mostly black, there are colors swirled into the pieces, filling some of the carved rivulets on the canvasses. Dadson favors neon, with shades of pink, blue, orange, green and yellow that look like they are from a Highlighter collection. Bringing these funky colors into the otherwise solemn pieces is akin to a cluster of flowers valiantly pushing up from under a concrete parking lot; i.e., Dadson lets the organic have the last word here, demonstrating how nature’s beauty and will are not easily suppressed.

Painted Plants, 2015, paint, grow lights, plants, installation dimensions variable, approximate installation dimensions: 93 x 135 x 108 inches

Painted Plants is a more obvious piece in terms of this message. Dadson places several large houseplants in the gallery and allows them to grow with the help of special filtered lighting. The plants are covered with nontoxic black paint, which fixes our attention on them more seriously than if they were left untouched. As the exhibition goes on, the plants will grow and eventually the black paint will no longer cover all of the leaves and stalks. Dadson’s placement of the plants in an interior space and his covering of them with a man-made substance first asserts humanity’s smugness about its ability to control nature and subvert it to its purposes, but the subtly of the plants outgrowing the paint reminds us that we cannot wholly control our natural world.

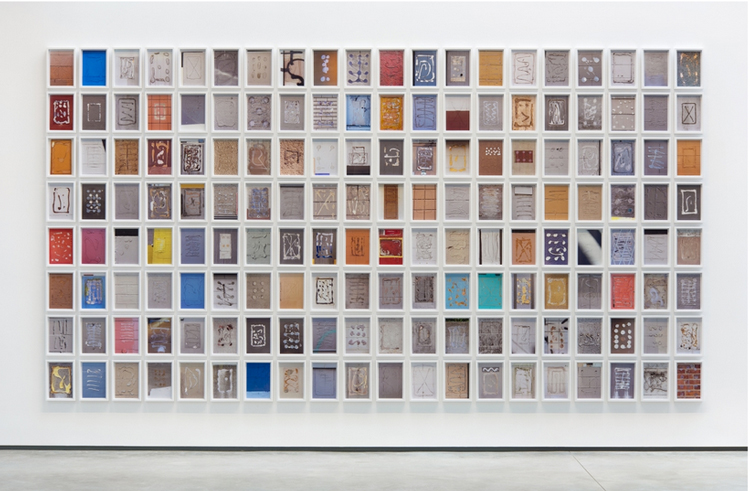

The last work, “Cuneiform,” may not supply the same immediate visual punch as the paintings, but is actually the most compelling piece in the exhibition. Consisting of 160 framed photographs in a grid formation, it features the marks left behind when advertisements or posters are pulled off of walls (the photos were taken in Los Angeles and Vancouver). As the title suggests, Dadson sees in these scraps and shapes the forms of letters, although these letters are alien to us, and in a language we cannot translate.

Each individual photograph could be shown on its own merits, sometimes resembling miniature abstract paintings. Colors vary, as do textures. Squiggles, splotches, and splatters are rife, but occasionally something more recognizable such as an X or a tree or leaf-like shape can be gleaned. The work offers endless potential for association and allusion, but one thing to take away that ties this piece to the others in this exhibition is the idea of the human mark, the human trace, and what is left behind.

Dadson’s approach to the discussion of humanity and its views toward and impact on the environment may not be as blatant as, say, Edward Burtynsky and Mark Ruwedel, but is similarly provocative and important, especially as he couches his message in art that is unabashedly visually appealing.

Andrew Dadson: Painting (Organic)

David Kordansky Gallery

5130 W. Edgewood Place

Los Angeles, CA

exhibit runs through July 11