Ana Serrano’s colorful cardboard sculptures of cityscapes and buildings, inspired by Latin American vernacular architecture, will be featured prominently this fall in two PST: LA/LA exhibitions. “The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility” at the Craft and Folk Art Museum will include her sculptures Cartonlandia (2007) and Chalino (2008); additionally, several of Serrano’s smaller works were recently acquired by Chapman University, where they will be part of “Emigdio Vasquez and El Proletariado de Aztlán: The Geography of Chicano Murals in Orange County.” Crafted from humble materials, Serrano’s works address a dearth of representation in fine-art settings of the experiences of Latino immigrants and Mexican-Americans.

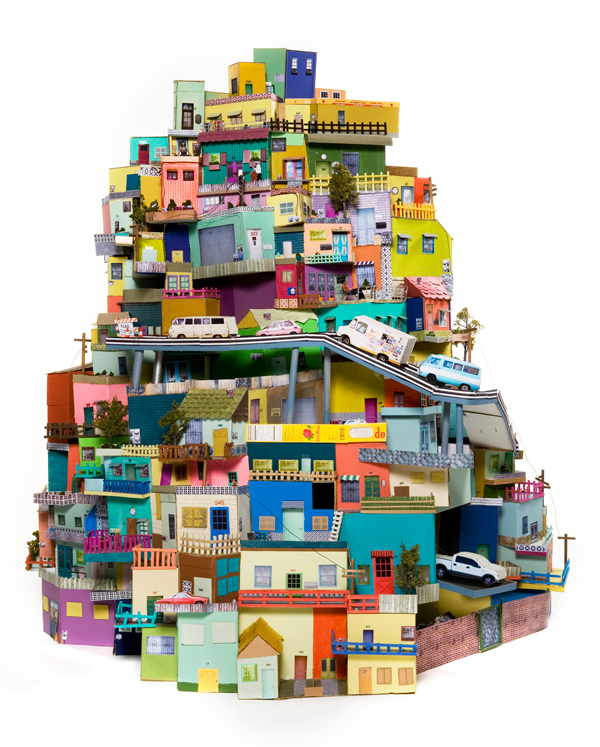

Cartonlandia, 2007, cardboard, inkjet prints on paper, glue, acrylic, 62 x 48 x 54″; photo by Julie Klima

The daughter of an immigrant factory worker from the Mexican state of Sinaloa, Serrano grew up in predominantly Latino South-Central Los Angeles on the border with neighboring Vernon. The idea for Cartonlandia originated during a trip to Guanajuato and blossomed during weekly visits to family in Tijuana. “I wanted to be able to capture a little bit of the spirit of an unplanned city,” she says. After determining the sculpture’s base dimension, she built haphazardly, letting one decision influence the next and using only readily available resources. The result evokes the serendipitous splendor of a hillside enveloped in rainbow-hued dwellings. It is important for her to represent these spaces, she says, because they were so central to her experience of growing up in Los Angeles and part of who she is.

Sarita’s #1, 2012, cardboard, inkjet print copies on paper, glue, and acrylic, 11 x 13 x 10″, photo by Julie Klima

Serrano aims to shift the representation of that cultural history in the art world. Much of her work represents Latino neighborhoods. Reminiscent of Mexican folk traditions like cartonería and tableau, her works monumentalize practical contemporary flair: a mural of multicolored ice cream cones adorning the mint green facade of Nevería (2012); intersecting American and Mexican flags painted on Sarita’s #1 (2012).

Salon of Beauty, commissioned by Rice Gallery, Houston TX, 2011, cardboard, paper, site-specific installation, photo by Nash Baker

Serrano generally portrays only exteriors, imparting a faraway feeling despite their handmade aspect. Salon of Beauty, her 2011 installation at Rice University, was a nearly life-size imaginary rendition of a Los Angeles block of storefront facades. “I like the dynamic that it’s a public space, but it’s very personal as well,” she says of her penchant for exterior scenes.

Ambling through different neighborhoods provides inspiration. “When I’m walking around looking for images, I like imagining who lives here, and what they might do or be,” she reflects. “There’s lots of small clues and architectural details that can tell you about a place.” Security window bars, satellite dishes, and air conditioning units are recurring motifs. “They’re not seen as worthy of further inspection,” she says, explaining her attraction to these seemingly mundane items. “They’re easily dismissed; they’re not considered any form of formal architecture. Yet there’s so many levels to them that I feel like I have to represent them.”

Neveria, 2012, cardboard, inkjet print copies on paper, glue, and acrylic, 12 x 13 x 13″, photo by Julie Klima

She began to notice distinctions between various neighborhoods after moving to predominantly non-Hispanic Downey at the age of 9. “I think my wanting to create these works that still have a craft base comes from my early childhood,” she says. Indeed, Serrano’s cardboard structures are reminiscent of the models of California’s early missions made by fourth graders across the state. Later, when she studied illustration at Art Center, Serrano began creating 3D fine-art pieces from cardboard.“I grew up here in LA in a working-class neighborhood, and it’s not a traditional material that you always see in a gallery space or art museum,” she says. “I like being able to elevate it, to make it worthy of being considered art.”

“I think representation really matters,” she says. Her ambition is to enhance appreciation of working-class Latino neighborhoods’ beauty and inspire others of similar backgrounds. “I think if I had seen a Latino neighborhood in a museum when I was younger, there would have been a connection there.”

Chalino, 2008, cardboard, 72 x 25 x 14″, photo by Julie Klima

Chalino, Serrano’s life-size monument to Chalino Sanchez, evokes Mexican folk statues and parade puppets. Her monochromatic sculpture celebrates the swashbuckling Sinaloan tenor who garnered fame in the U.S. by selling his corrido tapes at Southern California swap meets. Growing up in the ’90s, Serrano recalls multiple generations of immigrants and their Americanized children cohering over his music at parties. He was a prominent representative of Mexican-American culture, she recalls, and was able to bring together these two cultural contexts.

Though she recently transplanted to Portland, OR, her work remains anchored to Los Angeles; the difficulty of reconciling dual locations and cultures is apparent. Currently developing a February exhibition at Bermudez Projects, she explores neighborhoods remotely via Google Maps and gathers ideas and photos on bimonthly visits to Los Angeles. “It still informs my work, and it’s so much a part of me that I feel like I still know the city like the back of my hand—even though I’m not in it.”

All images courtesy of the artist.

See Serrano’s work at the Craft & Folk Art Museum, “The U.S.-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility,” 9/10/17–1/7/18.