Why even catalog these grievances? I just wanted to get a book published. The documentation of this tedious process wasn’t something that could hold much interest for the average reader, whoever that was, or any reader, if there were any left.

I had wrongly assumed that Melinda Waterform would offer some sort of response to the manuscript that she had begrudgingly received from me, if only to avoid any awkwardness when we next encountered each other. She had certainly been friendly enough in the past. Still, I couldn’t really blame her for balking. Now that she was a famous author she was probably being subjected to constant pestering from every corner of the literary world. If the positions were reversed, I wouldn’t get back to her either… or would I? I thought about it for a moment: If a friendly acquaintance were to humbly force their work on me, regardless of the quality of the work or my feelings about the person, I would at least get back to them in a relatively timely manner and offer some sort of half-assed encouragement, however insincere. I had done it enough times.

I usually resented it when unsolicited manuscripts were dumped on me, especially by people I barely knew. It was a presumptuous imposition, and the experience was seldom rewarding. One was never really in the mood to spend three or four hours, or even twenty minutes, reading a virtual stranger’s work, especially on a computer screen.

My over-awareness of this familiar dynamic had tainted my recent exchange with Melinda, and now ruined any subsequent interaction. But I had only asked her to suggest a possible path towards publication, not to read the work—that had been her suggestion—and she had almost guaranteed that she would at least do that. Her reluctance was understandable. But if she read the work, she might…

So many mights, so many maybes.

Mike Eupole’s agent, Susan Fumus Blear, did not get back to me. Mike had probably told her not to feel under any obligation to respond to me, and explained, no doubt, that I was an importunate no-hoper towards whom ordinary courtesies need not be extended; and he probably didn’t bother to read the published works that I gave him either.

It is a great luxury to be secure in readership and remuneration. As well as providing a functional incentive to one’s endeavors it must also engender an added urgency and vitality to the process of composition itself, in the knowledge that one’s words are destined to be read: a sensation that is entirely foreign to me.

The novel possesses a certain vitality because I assumed, while writing it, in the back-to-front of my mind, that it would be published.

It is now unfathomable to me that I was able to entertain this illusion for years on end.

After taking so much care with this one work, and having made considerable sacrifices—financial, social, romantic—in order to prioritize it, only to experience the most unjust, indefensible and degrading forms of rejection, there is a danger of the potential vitality being prematurely drained from any subsequent literary undertakings.

Maybe the novel itself—I wouldn’t call it a book because it doesn’t exist in that form—has become stale from being left alone for too long. Could it not suffer the fate of all organic process and rot, and wither, before it has even seen the light of day? It is, in effect, an impotent work of art. For two years it has been left alone – occasionally, and with increasing infrequency, tinkered with, much like its author.

Time is running out, vital forces are in decline, there is no demand for the product I slowly but relentlessly grind out; yet I perversely persevere, grinding away in an overly familiar void, pressing on in the face of inevitable rejection, because I don’t know what else to do with the remaining time that is mine, and because it’s too late to stop now, despite the absence of any kind of reward.

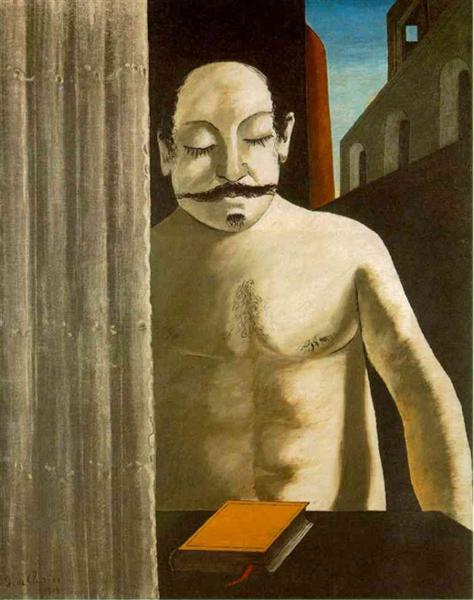

Giorgio de Chirico, The Child’s Brain, 1917.

In the interest of further time-wasting and reveling in deeper irritation, I googled Melinda Waterform and found a recent article that lovingly chronicled her advancing friendship with Jose Mutha Clapshoe, a young writer of ‘transgressive autofiction’ that I had found, from my few brief forays into his work, to be as boring as he was popular; maybe I was missing something. Melinda had also recently written an in-depth profile of a famously underrated, glamorously tragic, manic-depressive Italian poet(ess) who had lately been receiving a lot of long overdue critical attention.

So there were writers that Melinda helped out… and their reputations were already secure. On the basis of what I’d seen of her articles, she liked to draw attention to her own taste by writing about already revered figures, the more romantic and difficult the better. She wasn’t, in effect, helping anybody; she was merely strategizing, establishing her own position in the canon alongside writers she wanted to be associated with… or so I thought to myself.

She was very careful about who she advocated for, and mine was not a cause she cared to be affiliated with: there was no reflected glory to be had there. Why boost the career of somebody that is truly unknown—an old white male, moreover; inconveniently still alive—when you can draw attention to your own taste by championing an already renowned figure who will afford you a certain gravitas by association, and thereby place yourself in that pantheon?

“I’ll do it because you’re a neighborhood character,” she had told me. That callous remark, with the implication that the work, were she to read the sample she’d asked me to send her, was secondary to my status as a “character,” gnawed at me, completely disregarding, as it did, the quality of the work itself.

Naturally, she hadn’t bothered to get back to me. I could sense her recoiling from the reflected shame that attaching her name in any way to mine could tarnish her with. If I was a fictional character, she might be more warmly disposed towards me. You read about such a person in a book and it makes you feel special to recognize their qualities, but you meet them in real life and you look down on them. As a real person, I didn’t cut it.

The self-pity was killing me.

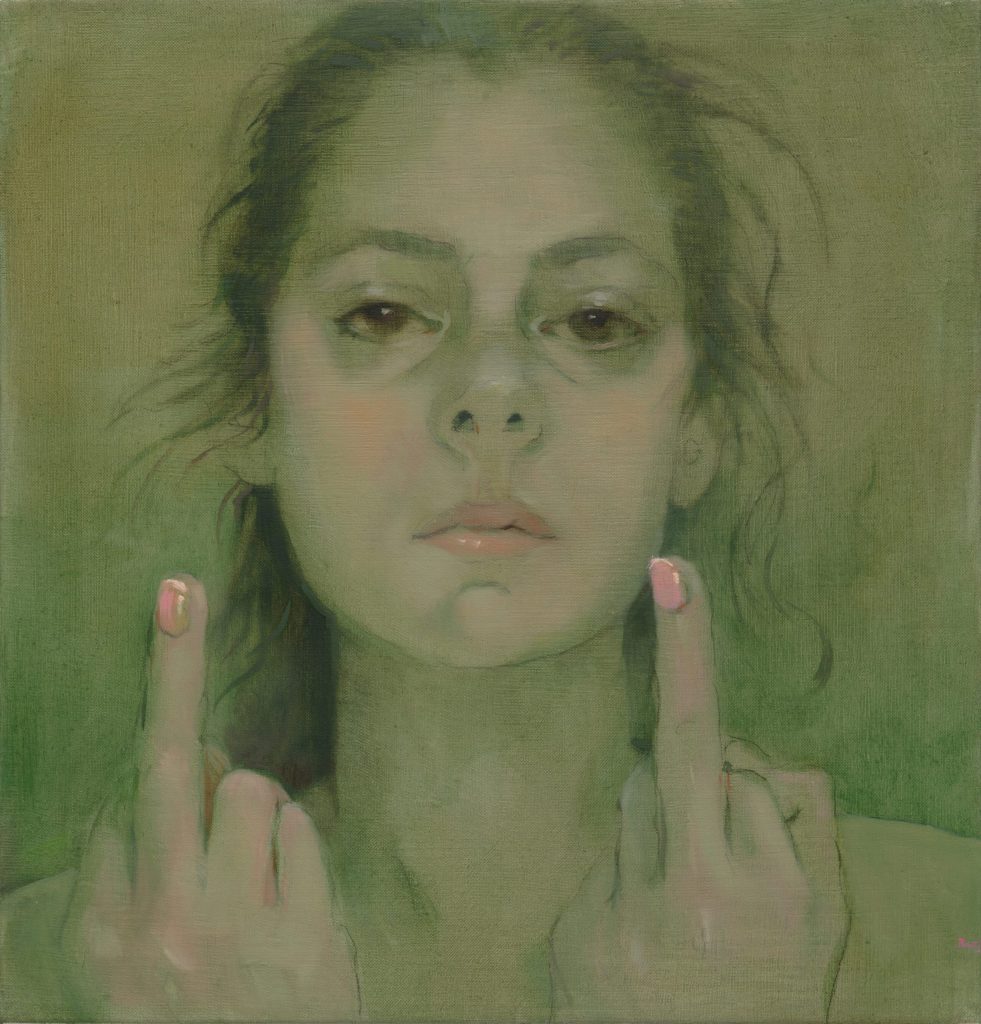

Ramon Casas, Decadent Young Woman. After the Dance, 1899.

All this stress and bitterness was the direct result of being involved, however marginally, in the literary world.

It was even beginning to interfere with my restorative walks, as there were now two renowned local authors to avoid, and be avoided by. I had noticed Mike Eupole crossing the street to avoid me on one recent evening, and suspected that he had altered the course of his neighborhood walks in order to bypass my apartment; while on my morning constitutionals I had to engage in stratagems of mutual avoidance with Melinda Waterform.

One summer morning Melinda crossed a leafy residential street directly in front of me, with a cellphone pressed to her ear and her leashed dog scampering and drooling alongside her. I stopped in my tracks and watched her pass by, with her dog’s proud asshole glistening in the soft early morning sunlight. I wasn’t sure if she’d seen me or not— she was so immersed in her phone conversation that she was probably oblivious to her surroundings—but it didn’t matter, as I was also avoiding her, partly in order to spare her the awkwardness of having to deal with me. It had now been several months since I had sent her my manuscript, and I regretted ever having approached her. The dynamic between us was so obvious, why not spell it out? You don’t read my work, so why shouldn’t I write about you? It’s not as if it’s very likely to be read, least of all by you.

Was this the best use of my depleting energies? Time was running out and all I could do was gripe about picayunities, rage against perceived slights, wallow in predictable regret.

My bitterness was beginning—continuing—to disgust me. The articulation of pettiness provided no satisfaction or cessation, and catharsis, if it even existed, which it didn’t seem to, was hardly sufficient justification for such a tireless outpouring of fribbling expatiations. Why not just ignore these ignoble thoughts, rather than carefully transcribing them?

This is Part VI of an ongoing series. Please see previous installments: Part I, Part II, Part III, Part IV and Part V.