“You’ve caught me in a really good mood,” said Jeffrey Poe, as he sidled up to the bar of an upscale West Hollywood restaurant.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” I said. “I was hoping to play up the ‘lonely at the top’ angle and find a backhanded way of comparing your fortunes unfavorably with mine. I guess I’ll have to ditch that idea.”

“I’m happy because I bought a new piece of furniture,” said Jeff, with the distinctively soothing and seductive tone of voice he has always had—the deceptively lazy and effortlessly polished bedside manner of a consummate dealer that has facilitated his ascent to the very pinnacle of art dealership as co-owner of Blum & Poe.

Talk quickly turned to a mutual passion.

“I hit a $4,000 trifecta at Santa Anita,” said Jeff. “I boxed three long shots that were all dropping in class.” Unlike with most horseplayers, I didn’t get the impression he was lying or exaggerating.

“That’s nice,” I said, not without a trace of envy. “I’m still trying to hit the Pick 6. Last time I was out there I hit the first five races. I singled a Baffert favorite in the sixth race. You couldn’t have singled a safer horse… on paper. It was too good to be true, of course.”

“Lost by a nose?”

“A lot more than that, actually. Beats like that can be very embittering. But at least it put me off going out there for a while, which is a good thing. It’s hard enough dealing with all the other obstacles, but then you have to deal with yourself. It’s psychological mayhem. I make my picks the night before, then I go out and deliberately thwart myself. It’s too madly overstimulating out there.”

Jeffrey Poe and John Tottenham.

“That’s why I have an online account. I don’t have to deal with the people,” said Jeff. “I get the Form the night before at a liquor store in Santa Monica, and I’ll lay there on my chaise longue next to the pool. I have my dogs with me and we make picks.”

“The dogs help you handicap?”

“Yes. I put the alarm on my phone and two minutes before the race goes off we’ll waltz inside and watch it on TV.”

“You look healthy,” I remarked.

Jeff pulled out his iPhone and displayed the Health app. He clocks about four miles every early morning, walking the canyons near his house.

We downed our drinks and were escorted to a table.

“Can we have a quiet table. He’s interviewing me for Vanity Fair,” Jeff said to the maitre d’. “Watch,” he whispered to me, “they’ll comp us.”

We were seated at a comfortably upholstered curved banquette and menus were handed over. “I have heard of some of these,” said Jeff, perusing the lengthy wine list. “But I think we have to order a bottle based on the name. We have to drink the Joy Fantastic.”

“Is that a hearing aid I see in there?” I asked, upon observing a tiny device attached to Jeff’s ear.

“I’m deaf, man. I have hearing aids.”

“I have terrible tinnitus,” I said, picking a toasted almond from the tin of nuts and olives that had been brought along with the bread.

“I do too. I have no memories but I have tinnitus.”

“You think it’s from the Blue Daisies days?”

“Banging metal rods on an anvil. What was I thinking?” said Jeff.

Young Jeffrey Poe.

When I first arrived in town, more years ago than I care to remember, Jeffrey was one of my first friends. At the time, he was one-third of a band of incorrigible young exhibitionists called the Blue Daisies, who gave wildly abrasive performances in varying states of undress. A sort of industrial boy band with considerable chick appeal, their repertoire included such charming ditties as “Suck Me” and “Hand Job.” Among other innovations, they ushered in the genital sock-wear fad that received mainstream exposure from the Pale White Silly Puppies.

“I just wrote some lyrics and I could sing a bit and I had a tiny bit of presence,” said Jeff modestly.

“And you took your shirt off, and your pants.”

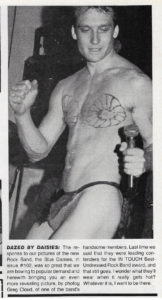

“I was kind of ripped so some performance photos made it into a gay porno mag. They put me in two issues in a row, I guess because so many guys were jerking off to me. The second time they gave me an entire page. I look back and I didn’t realize what a peacock I was. It was taken at the Anti Club. We were opening for Sonic Youth.”

“I was there. Kim Gordon gave me her phone number,” I said.

“Did you call her?”

“I did. Her husband answered the phone.”

“How did that go?”

“It was slightly awkward.”

“She’s a major figure these days.”

“Yes, she’s turned into the Hillary Clinton of rock and roll.”

“That sunset glare is hurting my eyes,” said Jeff. Harsh light was flooding in through a window above a table occupied by a party of five.

The waitress brought the Joy Fantastic and poured some into a glass for Jeff to appraise; it was obvious to her that Jeff was the one who got to taste the wine. And it was to his liking.

“That is good. It’s nice and soft and clean and fresh… Could you pull the blinds down over there,” he added in the smooth manner of someone who is used to having his gentle commands carried out.

“Here’s to us. We survived,” said Jeff, raising his glass.

“I always thought of you as being a bit of a stud,” I said as we clinked glasses. “To me, an Englishman abroad, you were the living definition of a hot young American stud. Blonde, muscular, very confident.”

“Thank you for that, I’ll take it.”

“You’re welcome. I’m secure enough in my sexuality to pay tribute to another man’s beauty.”

“Likewise. You were like a pretty John Hawkes.”

“The writer?”

“No. The actor. I remember, we’d just walk into a bar, and sometimes…”

Another dish of nuts was placed in front of us.

“I was a shy narcissist. I didn’t realize what I had. I don’t think most young people do,” I said.

“In those days, perhaps. Today it’s a different story, with social media. It’s tragic. It is the end.”

The Blue Daisies recorded one album before folding. Jeff and fellow ex-Daisy Nic Greene went on to form a somewhat more commercially viable outfit, a two-piece band called BOF (Blissed Out Fatalists). They burned hard and faded fast. In the interest of self-immolation, they rejected the advances of major record companies and blew other golden opportunities.

“I really did think that BOF would amount to something,” said Jeff. “What’s the point of this interview anyway?”

“Good question. It’s supposed to be a conversation between two people who are involved in different fields of the art world. There’s going to be an Artillery issue filled with such encounters, of which this will be one.”

“Let’s figure out what we want,” said Jeff, as he surveyed the short but complicated menu.

“What the hell is bulgar and green harissa?” I asked.

“I’m getting the fish.”

“I was going to get the fish though.”

“That’s okay. We can order the same thing.”

“You know, all this frivolous stuff about sex, gambling and rock and roll isn’t going to fly with the art-damaged Artillery readership. Let’s try to steer this conversation into something more relevant to the arts,” I suggested.

“Good idea,” said Jeff, with characteristic magnanimity. “What were the chances of our both ending up in the art world, our lives running a parallel course?”

“They’re hardly parallel. If there was a graph the lines would only intersect at the very beginning. I would never have predicted you’d get involved in the art world.”

“Me neither. I just fell into it,” said Jeff.

Indeed, there were no signs at that time, in the mid-1980s, that Jeff possessed any interest or ability in the course he has subsequently taken. Following the dissolution of BOF, he turned down an offer to drum for Jane’s Addiction. An autodidact who never graduated from college, Jeff worked on Chris Burden pieces in the late ’80s before becoming a preparator and an assistant at various galleries. Blum & Poe opened in the mid- ’90s in Los Angeles. The gallery achieved immediate success and there are now satellite galleries in New York and Tokyo.

John Tottenham (R) with Blue Daisies band member Nic Greene (L)

“You used to do those beautiful drawings of Victorian architecture and floating girl’s heads,” Jeff said.

“Don’t remind me. I should have kept going. I retired in my 20s and picked it up again in my 40s—a weird trajectory of willful self-sabotage.”

“But you got into poetry.”

“Better late than never,” I said between swills of the Joy Fantastic. “That was a desperate last resort. Having wasted so much time, I had to shrink my aspirations down in order to produce anything. Poetry and small drawings are unlikely to set the world on fire.”

“But you’re not exactly a pyromaniac.”

“True.”

“Remember that morning when we had to go and house paint after we’d been up all night doing speed?”

“Yes.”

“That was so much fun. I miss it so much,” said Jeff, wistfully. “The thing about doing drugs like that is I felt absolutely fucking invincible. Are you still friends with…?” Jeff mentioned a certain ruthlessly ambitious artist (identity withheld in order to avoid shameless name-dropping and potential recriminations) with whom we were up all night doing gak during our house-painting days.

“No, he doesn’t speak to me anymore. Maybe I wasn’t obsequious enough. These oversensitive egomaniacs are hard to deal with, as I’m sure you know. I offended him somehow. Or maybe I offended his girlfriend and he took offense, I can’t remember. It’s mostly a blur. In any case, he lives in a mansion in Bel Air now.”

“Actually it’s in the Palisades,” said Jeff, who was apparently still on friendly terms with this now massively successful artist.

“I remember us spending a lot of time lying around hungover when I lived on Western Avenue,” I said.

“I do too. It was almost like we’d nap together. You have to put that in the article because there was a beauty to it, despite all the pollution of being high on drugs and being crazy. I was out of my tits.”

Jeffrey Poe in a gay magazine.

The waitress had pulled the offending shade down but it had been hoisted back up again by the diners.

“That fading Dylan hair of yours is helping to block out the sun,” said Jeff.

“It’s a good thing you’re not sitting on this side of the table then,” I rejoined.

“You can talk to my bald spot if you want,” said Jeff, unabashedly. “It’ll answer you back.”

“It looks like a sacred place.”

“It is a sacred place, totally.”

But, lest we digress, back to the hearing aid:

“It helps with the tinnitus. It allows me to hear other things.”

“It’s very discreet.”

“It’s very expensive.”

“How much?” I asked, indiscreetly.

Jeff quoted an astronomical sum.

“I don’t suppose my low-grade health plan would cover that.”

The salad with the “End of the world citrus” arrived—containing sprouted greens, cubes of cucumber and sour apple slices.

“Your sense of wonder is still intact,” I remarked.

“If you get bitter, you’re fucked. You have to stay engaged. You know these people are really turds for putting that window shade back up. I’m going to actually demand it go down because we’re doing this Vanity Fair article.”

The waitress was summoned. “The sun will go down in a minute. They’ll live,” said Jeff, more firmly this time.

“We’re supposed to be talking about art,” I said.

“Oh.”

“Are you still showing Henry Taylor? He’s great. He breaks into song in the middle of a conversation.”

“He’s incredibly in the moment. Even when the moment is completely gone, he’s still in it. There is no strategy to Henry, and as an artist today that’s almost impossible to find. He’s pure. He’s fucking pure.”

“He came through the academy, didn’t he?”

“He did and it clearly informs him, but at the end of the day he’s one of those artists who just has to work; his hands are always moving, that’s just the way he is. Seriously, he has an intuitive gift. There are no other artists like Henry Taylor, and that’s why he’s gotten to where he’s gotten. He just presented new work at the Venice Biennale.”

Jeff went on to lavish fulsome praise on the curator of this year’s Biennale, with whom we had both been great friends back in the pure old days.

“He hasn’t talked to me in years,” I said. “He moved on. I wasn’t the sort of person he wanted around as he climbed his way to the top. Can’t say I blame him. I’m still leading much the same existence as I was when we first met. On the few occasions that we’ve subsequently run into each other, he has been conspicuously ill-at-ease in my company. I offended him somehow.”

“How?” Jeff asked.

“I can’t remember. Don’t ask.”

“It’s a wonder that I’m still talking to you.”

“We only see each other once every five years. That way nobody gets hurt… So he’s doing well?” I tentatively added.

“He’s doing great. You know, he’s curious. At the end of the day, isn’t that what we want to be?”

“Curious?”

“Yeah.”

“Lack of curiosity is unforgivable,” I replied.

“We like to be curmudgeons. It’s a default mechanism. I’ve been waiting my whole life to be a sad-sack senior and I’m finally on the cusp of it. But I honestly do want to be engaged in the world.”

The fish arrived, lying on a pillow of pungent garlic alongside several robust spears of asparagus—the virginal white flesh slipped softly from its bones.

“You must frequently find yourself in a very engaged position,” I naively remarked.

“Not really in the way people might think, because I have to deal with a lot of business stuff. When you’ve got three galleries and 30 employees spread out over the world, it’s like a 7-Eleven— somebody’s always open, it’s exhausting and stressful. Luckily, I’ve got a business partner, or I’d kill myself. That’s why, in a certain way, I look at you and I think you’ve skirted it all.”

Tim Blum and Jeffrey Poe.

“I haven’t though, at all.”

“You’re not responsible for anything but yourself.”

“That’s not necessarily an advantage. It’s all I’m capable of. I’m still scuffling.”

“How did your show at Bergamot go last year?”

“Reasonably well, sold three-quarters of it.”

“How’s the process of making drawings?” asked Jeff, in an admirable attempt to stick to the subject.

“I only do it when I have a show. I used to do these drawings of abandoned buildings and desolate streets, and someone said ‘You’re supposed to be a poet, throw some text on them, they’ll sell’—so I did, and they did, to some extent. But mostly what I’ve been doing for the last three years is writing a novel.”

“Can I see it?”

“No way. I can’t show it to anybody I know. I’m only interested in the opinion of influential strangers.”

“What’s it about?”

“Well, I have no grasp of plot, character or dialogue and my imagination dried up years ago, so I’m obliged to rely on personal experience rather more than I would prefer or approve of. It’s very likely that nobody will ever read it.”

“A novel that will never be read.”

“Why not?”

The sun went down over our table and the Joy Fantastic induced a nostalgic glow.

“I really do miss those times,” said Jeff, alluding to the halcyon days of our youth in the relatively untarnished and untamed Los Angeles of the 1980s.

“It seemed like there was a lot going on downtown at the time,” I said. “But compared to now, I guess there wasn’t. It was a squalid paradise, looking back on it. The bars, the cafeterias, the art scene. I guess kids nowadays are getting the same charge out of it but in a different way.”

“No,” said Jeff, emphatically rejecting that notion. “Because there’s no boredom anymore. People are always on their phones. Nobody is able to stare at a wall or actually engage in a moment where there’s a breath. It’s because… we’re fucked. We were forced to be with ourselves then. There wasn’t all this crap, and this crap has created all this noise…”

“Aural pollution.”

“Yeah, we all have tinnitus, in our own way—visually, aurally, it’s fucking exhausting, and you’re tethered. Those were days when things weren’t tethered, and, quite honestly, we were at the edge of the edge, in the darkest corner of the underground. There was a time and a place for us and it was organic. I don’t think there’s organic shit going on anymore.”

“We have digital lives and we had… what’s the word?”

Jeff was stumped.

Jeffrey Poe and John Tottenham.

A couple of minutes later, I remembered the word: “analog.” Yes, we had analog lives. But by then Jeff was musing about gambling again.

“The other thing I’ve done, that you were 100% right about, is that I do not bet horses that come from Golden Gate.”

“Just toss them out, even if they’re favorites,” I said. “You know, the intricacies of handicapping are very boring to anybody who isn’t into horse racing, which is most people, especially nowadays. But don’t worry, this won’t make the final cut.”

“Horses dying at Santa Anita. It’s a bad thing. A horse died on Preakness day,” said Jeff, in reference to the recent spate of equine fatalities at Santa Anita.

“Yes, it’s hard to put a positive spin on dying horses. Did you watch the Preakness?”

“No, I was on a plane to Europe. Shall we order dessert?”

“That’s all right.”

“The track is dying. We’re dying. We’re like old horses dying. The whole game is going to be over soon,” said Jeff.

“How was your prostate exam?”

“Perfect. I’m healthy. My morning constitutionals keep me in check.”

“I doubt I’ll get an article out of this,” I said. “It’s exactly the sort of thing I hate: two old geezers rambling on about the good old bad old days with self-congratulatory tales of bygone excess, while bemoaning the state of today’s youth. We haven’t gone into any depth on the subjects I was hoping to explore. You know: success, failure, age, death—that sort of thing.”

“We sort of touched upon them.”

“I guess so. It’ll come off as self-indulgent, but it’ll have to do.”

“We’ll have to have another meeting,” said Jeff, slapping a credit card on the table. “This is a business dinner. You’re a huge client.”

They hadn’t comped us.