Inside American prisons, thousands of men sequestered in tiny, dim rooms spend their lives waiting to die. Outside, this marginal population is hardly considered, except as a seamy abstraction. SoCal-based artist Amy Elkins finds inspiration in prisoners’ hermetic introspections. Through her vividly evocative photographic series, “Black is the Day, Black is the Night” (2009–14) and “Parting Words” (2014) she explores the psychological effects of confinement and execution.

Physical isolation can efface one’s memories and alter personality. Themes of remoteness dovetail with Elkins’ intriguing manner of aggregating written descriptions and found images into “long-distance portraiture”: representations of people whom she cannot actually photograph. Many of her photographs are surprisingly painterly. In high school she studied painting and collage. She then earned a BFA in photography from New York’s School of Visual Arts and spent four years as a photo editor with Major League Baseball, until deciding to focus on her art.

Amy Elkins, Leonel Herrera, Exercution #58

Elkins’ primary subjects are men. “I grew up a tomboy and spent a lot of time with my brother and dad,” she offered in explanation, later adding that she enjoys the riddle of trying to understand others’ perspectives. She conceived of her prison projects after a missing relative turned up in jail. Finding his mugshot online sparked her fascination. At that time, she was photographing male rugby players. Wounded, sweaty and strapped with ice packs, players sat exhausted before her camera immediately after games. Their portraits emanate a dignified serenity that belies their fierce sport. “Rugby players play violence,” she reflected; whereas prisoners were convicted of real violence.

Amy Elkins, Ignacio Cuevas, Exercution #39

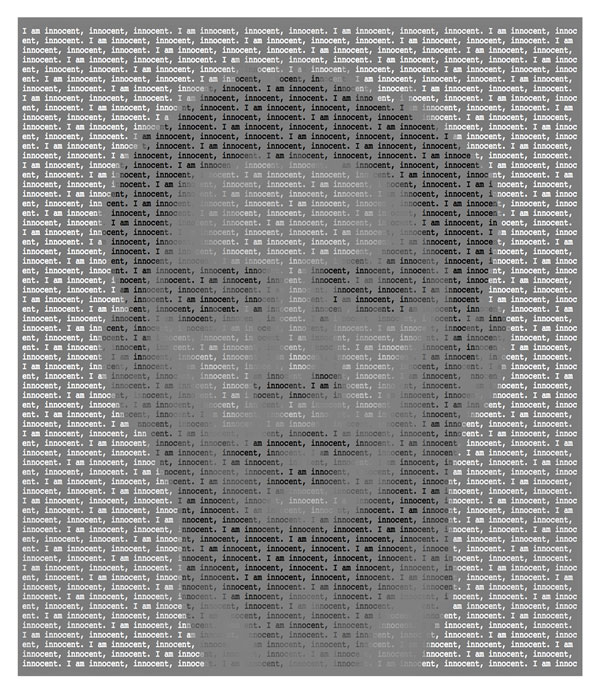

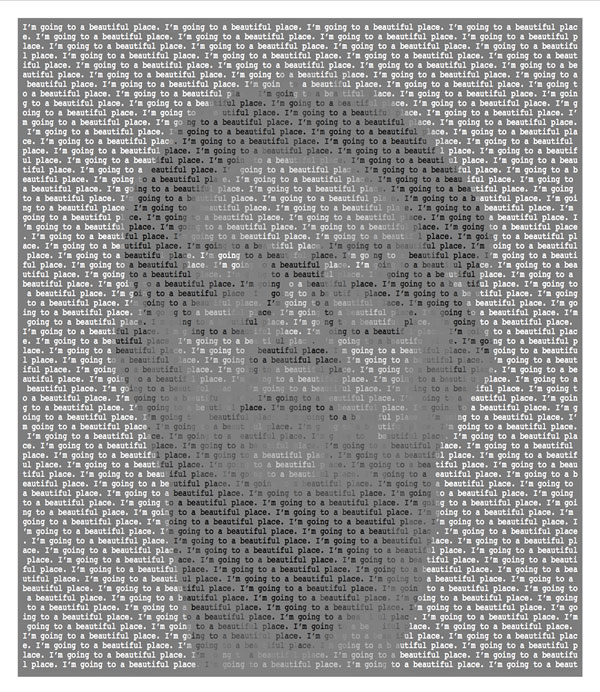

Elkins soon found herself writing to several men serving life or on death row in various penitentiaries. Brutality may have landed them in prison, but now powerless, they were philosophical. Instead of discussing their crimes, prisoners shared emotions and art. Elkins titled her project “Black is the Day, Black is the Night,” from a poem by a pen pal in solitary confinement. She had several of his verses printed black-on-black, legible only under certain reflective conditions. These photographic emblems function as collaborative concrete poetry.

More traditional snapshots depict captives’ correspondence: calligraphically addressed envelopes, cards and letters, meticulous ballpoint drawings. Some are infused with affecting irony, such as a Christmas card emblazoned with “Peace, Joy, Love.” As she developed the series, Elkins became so engrossed in imagining her correspondents’ ascetic lives that she re-created their makeshift prison tools, including a watercolor set fashioned from candy dissolved in tap water, and a jump rope braided from torn bedsheet strips. She sometimes exhibits these eccentric objects alongside her images, and documents them photographically. In contrast to these tokens of prisoners’ creativity and ingenuity, she also portrayed the more dismal trappings of life behind bars, like a prison food tray acquired from eBay.

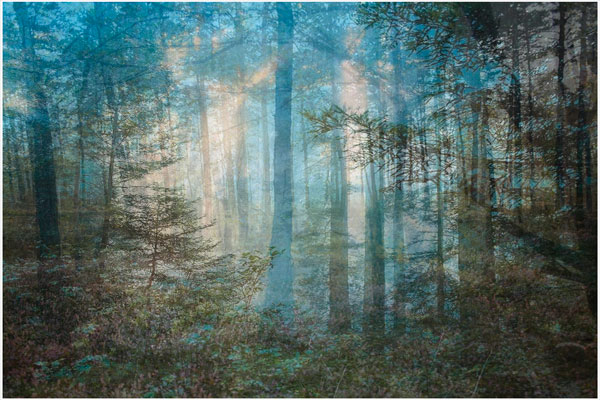

Amy Elkins, Four Years out of a Death Row

Sentence (Forest), 2011

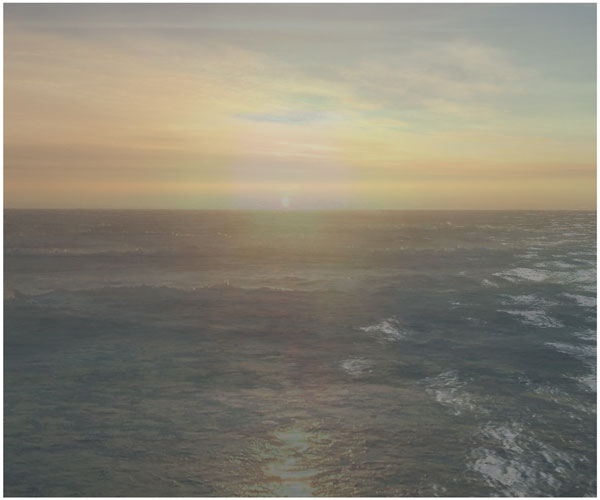

The most haunting and eloquent images of the series are imaginary landscapes. In their letters, inmates frequently expressed yearnings for specific locations important to them. Elkins herself wanted to envision these places for which her pen pals pined. Determined to capture them pictorially, she devised a list of scenes they had mentioned. She found images online and layered them to form composite scenes, such as Twenty-two Years after a Death Row Sentence (Ocean). Elkins speculates that years of incarceration would have muddled inmates’ recollections. These blurry, fictive vistas seem to shimmer like eerie mirages. Each landscape’s nebulousness symbolizes the illusory nature of memories and their mutations over time.

Amy Elkins, Twenty-two Years out of a Death Row

Sentence (Ocean), 2011

Three months into her correspondence, Elkins received news that a pen pal had been executed. This inspired “Parting Words,” a series of posthumous portraits of inmates overlaid with their last statements. These images exude stark, somber lyricism. A nearly floor-to-ceiling gallery installation of them evoked the morbid, stifling heaviness of an execution chamber’s block wall.

Elkins’ prison projects build on her other projects’ explorations of portraiture, masculinity and stereotypes. Ancient Chinese philosophers viewed boundaries between masculine and feminine as protean. The Tao Te Ching advises, “Know the masculine, keep to the feminine.” The yin-yang symbol contains white within black, black within white. Yet in our modern society, things are often more polarized.

Amy Elkins, Benjamin, Age 21, Corps Dancer,

Royal Danish Ballet Company,

Copenhagen, 2012

Ballet, for instance, is frequently stereotyped as feminine, despite the fact that many of its dancers are male. It is physically demanding and requires a great deal of strength. In “Danseur,” her portrait series portraying male dancers, Elkins explores ballet’s masculine angle. She shows a different side than is stereotypically considered, while representing dancers’ more genteel side of masculinity as opposed to rough rugby players. Albeit in a different way, the ballet dancers are equally athletic and masculine.

Amy Elkins, Lucas, Age 12, 6th Year in Royal

Danish Ballet School, Copenhagen,

2012

As she photographed them, Elkins’ dancers, like her rugby players, were exhausted after exercise. Yet athletes have the ability to replenish their strength by resting, whereas Elkins’ prisoners are at a physical and emotional dead end. There is no exit from their situation.

“I kept thinking of this idea of hyper-masculinity, but also that they’re now in this position of ultimate vulnerability in that they’re confined. They don’t have any control over their own lives anymore,” she explained.

Amy Elkins, Zak (Second Row, University Team

Captain), Princeton, NJ, 2010.

In opposition to the open spirit of her project, Elkins’ use of the term “hyper-masculinity” seems unfair in its essentialization. While most violent criminals are male, it does not follow that violence is necessarily associated with heightened masculinity.

“Hyper-masculinity” is the ultimate stereotype. Ascribing “masculine” or feminine to traits that are not strictly biological seems unnecessarily polarizing. To some degree, we all transcend our gender. Elkins’ ballet pieces show a different side of masculinity that has nothing to do with violence. In some respects, her ballet and rugby photos are more effective than her prison projects in conveying various, seemingly conflicting nuances that go beyond stereotypes. This is especially true of the rugby series, which lives up to the title “Elegant Violence.” One senses the ambitious, fierce competitive impulse behind the players’ tranquil poses. At the same time, the prison projects are more ambitious in their extremism and in their creative interpretation of photographic portraiture.

“Black is the Day, Black is the Night” seems an allusion to its polarized perspective. Like the tiny cells that prisoners are forced to inhabit, the project’s scope is narrow in that Elkins focuses on their viewpoints without discussing the impulses and actions that landed them there. The prison projects are laced with the prisoners’ fear, sadness and powerlessness in the face of institutional control. As writer Rebecca Solnit noted, “Violence is first of all authoritarian. It begins with this premise: I have the right to control you… Whatever fears, whatever sense of vulnerability may underlie such behavior, it also comes out of entitlement; the entitlement to inflict suffering and even death on other people.” If these men are marginalized, how much more so are their dead, buried, forgotten victims and victims’ families? Yet Elkins’ work is fascinating because it provokes these questions; it forces us to question stereotypes, and the foundations of what we think we know and believe.

Elkins won the 2014 Aperture Portfolio Prize for both prison series. Much of their power, it seems, lies in their sheer audacity. They expand definitions of photographic portraiture and expose the slipperiness of black-and-white notions of justice and injustice, violence and calm, vitality and mortality, indictment and empathy.

Clearly, empathy is at the heart of Elkins’ work. “Most of them said they were innocent, and I didn’t take sides,” she said of her pen pals. As essayist Leslie Jamison observed, “Sometimes empathy is really about throwing up your hands and saying, ‘I don’t know.’” Elkins’ imagery of the darkness in the lives and deaths of these men may be morose, but optimism is intrinsic to her determination to see the world from their perspective.