“We outside!” Chance the Rapper exclaims into his microphone. The sky is near black at maybe seven minutes after 8 p.m. in Downtown Los Angeles. Third weeknight of October. Chance had been and would be again, soon, rhyming his way through a song. The Chicago MC had been in the midst of vocalizing about his heart and his God and the shifting tides of life.

Chano—as more ardent fans might call him—stood on top of the Museum of Contemporary Art’s roof while he did his thing.

It’s our inside-out pandemic-era update on “in the house.” We Outside. And when Chance proclaimed this, approval shouts swept through MOCA’s disproportionately Windy Citizen–filled courtyard and back up toward Chance and the night. Here was that vibe called dope.

Around the artist, a drone hovered and dropped and rose to document this hip hop performance. We saw it on a 12×14-foot screen attached to the MOCA courtyard wall. Or we could take in Chance both in the flesh and on video. Determine our own adventures.

Novel as Chance’s show was, his sky performance and video work were but components of this weeknight outside.

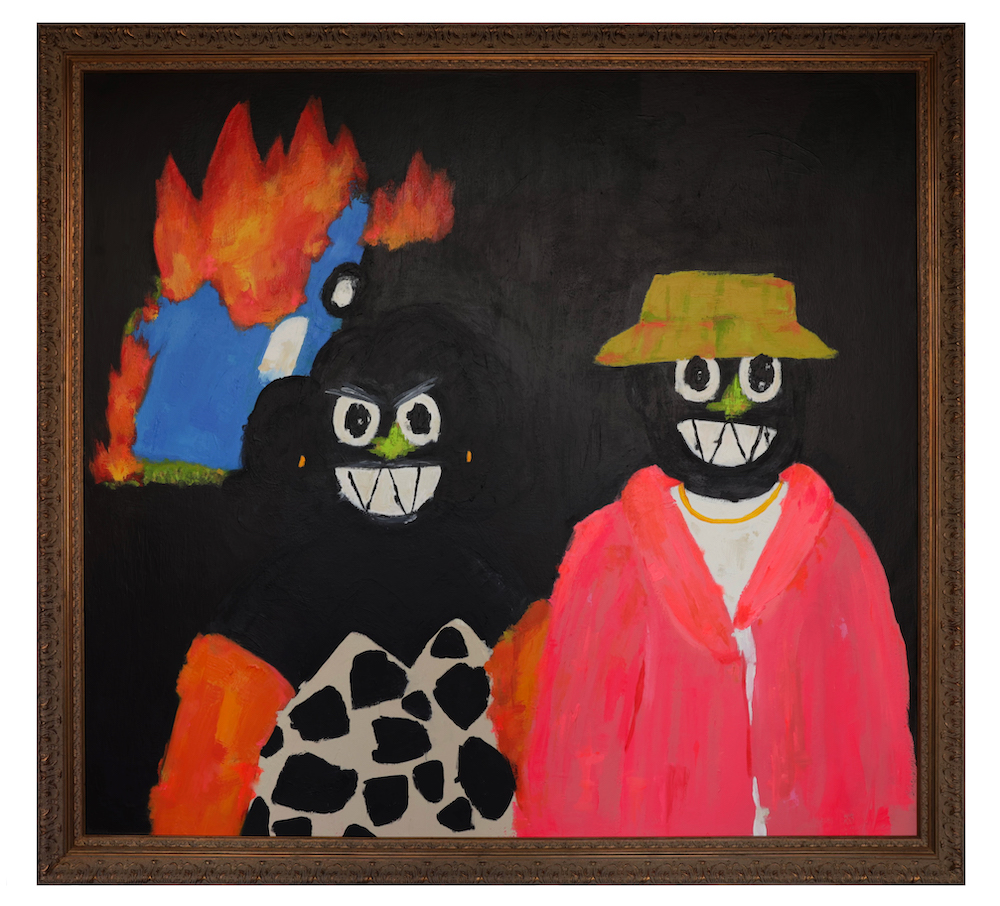

When the MC returned to Earth, he met up across the courtyard with Chicago painter Mia Lee for the unveiling of YAH Know, a new work created in collaboration with the musician. This LA event is part of Chance the Rapper’s reset as an amplifier of Black art in museums, spaces that remain unsuitably absent of makers and faces that look like his. Humans who vibe like him.

Freshly awakened to the need for Afro-Diasporic connection in all that he produces, Chance began by producing the “Child of God” exhibition at his hometown art institute in March and is embarking on museum shows that are as much about the crowds as the art combos put before them. This reframing’s second half is a music-focused event planned for January in Accra, Ghana. The show’s being done in collaboration with Vic Mensa, Chance’s Chicago homeboy who identifies as Ghanaian.

This night in DTLA is Chance’s second museum event. Neighbors watch from the tall apartment buildings adjacent. Style-icon Russell Westbrook of the Lakers is in the courtyard, as are undoubtedly mid-level designers who’ve Lyfted over from the Fashion District. Onscreen in one drone perspective, spot-lit Chance the Rapper was downtown’s most prominent element, dwarfing the boundary that is the 110 freeway.

“Niggas at the museum!” Chance offered, again between raps.

To talk about the highs and lows, the ups and downs

The friends that I had to hide to come around

They told me that I knew you’d always come around

Come around, come around, come around, come around

—Chance the Rapper, “The Highs and the Lows”

Chance, Vic Mensa and Nikko Washington on shooting day for “Bar About a Bar” music video. Photo by Keeley Parenteau.

Chancelor Johnathan Bennett, 29, leapt boldly into the production of musical art 11 years ago with 10 Day, a mixtape that he started while home from prep school on a cannabis suspension. The Kanye West–influenced song collection had him on the Western world’s underground rap radar while still finishing up at Jones College Prep. In 2013 he released Acid Rap, an acclaimed “tape”—hip hop mixtapes were a digital phenomenon by then—that both showcased how well he paired with Childish Gambino and brought Chance a genuine following. He’s called that song collection, “an allegory to acid.”

In April of 2015, Bennett lectured at Harvard University’s Hip-hop Archive & Research Institute. Later that year came the life-turn that supremely jolted Chance in substance and spirit: His daughter Kensli was born with an atrial flutter. Chance reconnected to the Christianity with which his grandmother raised him.

Not only did the subject matter of the music Chance put out after his daughter’s arrival become more spiritually oriented, but his sound also itself became more reflective of its local influences: One doesn’t have to listen hard to hear R. Kelly, Chicago blues and house. Above all else, gospel elements began to propel the records he rapped on.

Chance’s appearance in 2015’s “Ultralight Beam”—the opening track on West’s The Life of Pablo—was foremost a jawdropping debut. After flourishing on feature performances of singers such as James Blake and Justin Timberlake, Chano on “Ultralight Beam” established himself as a vanguard rap world player, within 16 bars.

He would cultivate the energy and freedom that being an independent mixtape star brings through his 2016’s Coloring Book, which the Grammys named best album despite being released as a mixtape.

At any time after 2015, Chance the Rapper could have marketed himself strictly as a gospel artist—Lecrae 2.0—and made an ethical killing. Instead, he has leaned into the artistry of hip hop.

Painting from the “YAH Know” video shoot. Photo by Keeley Parenteau.

“Fine arts are about exclusivity, right?” Chance rhetorically asked about elitism on the day we sat in the Sun Rose Room, a smart music space with wood tabletops located upstairs at the Sunset Strip’s Pendry Hotel. Here, we’re back near summer’s end, exploring the tensions within the museum world—and his biggest move since embracing Christianity.

In regular life Chance is much taller than he appears looking at him on a rooftop. Slim and brown with a high forehead and giant eyes like the Disney cartoon character that he has indeed played—Bush Baby, Lion King—the artist has just finished scrolling through digitized images of paintings that played big in the development of his visual sensibility. Widely known Chi-town artists like Ernie Barnes—whose art sold for $1.6 million on September 6—and more locally popular painters like “Black Americana” stylist Annie Lee are on his phone.

“Aesthetically Black painting. There’s a certain style of painting that I grew up around.”

Prep school took him to The Chicago Art Institute. The walls of his grandmother and her associates instilled the sensibility. Of the hundred or so professional MCs I’ve interviewed, Chance’s speaking voice contains the least distance from their performance voice.

About that art world exclusivity?

“It’s about having an artist or their art who’s heavily sought after, hedging a bet on something growing in value, also,” he said. “I think hip hop is intrinsically about access, about giving us—the people who didn’t have a space—space to be and talk about who they are.” Which would explain the MOCA exuberance, both on that roof and on the courtyard floor.

Chance’s output can find him stuck between two American aesthetic silos—too sophisticated in presentation to be a commercial radio force and a bit unorthodox for the average American museum. So far.

“When people compliment me even, they say, ‘Oh, he’s more than a rapper,’” says Chance. “But what they’re doing is devaluing what it means to be a rapper, and what hip hop is about. Which is community. Which is access. Which is representation. Which is being truthful.

“My rap has taken me all over the world,” Chance told me on the Strip. “My voice has been places that my feet have never been.”

His feet made it to Venice, Italy, last April, for the Biennale. He may have been just a rapper shooting a music video in the midst of some of the finest artists of African descent alive, but he says the diaspora embraced him. Chance was blown away to find how much wisdom and kinship they shared with him. And he didn’t receive the love simply because he’s a famous person whose face got his new crew admission to elite parties their own art-world currency couldn’t always cover.

These conversations with the diaspora’s creme de la creme stirred a plan to at least unsettle assumptions and economics around African people and art.

“They were explaining to me that there’s starting to become a widely publicized Black Aesthetic, and that’s mainly portraiture with Black subjects painted a certain kind of way. And what it does is make white collectors look for that aesthetic,” he explained. The paintings of his youth have been monetized. But to what end?

“Knowing that there are more and more artists from West Africa—and Black artists globally—whose status is growing, their price on sales is going up, and that’s the specific kind of art that [collectors] are looking for. And that there’s a sense of reward or that they’re doing something by investing in a Black artist. But Black art is Black art when it’s being created by Black people. All the people who work in abstraction or just don’t center their pieces on portraiture or if it’s ‘not Black’ at face value—their works are being pushed aside, basically. Or devalued.”

Pigeonholing multimedia attractions such as the one Chance gave The Art Institute and MOCA is a tough gig to undertake. Downtown, the museum architecture found itself involved. MOCA Director Johanna Burton emailed to say, “It was thrilling to see [Arata Isozaki’s Pritzker Prize-winning] building activated in that way”

Chance and Mia reviewing takes from the “YAH Know” video shoot. Photo by Keeley Parenteau.

The drive behind The Rapper’s museum events and that upcoming Ghana concert is as much past racial elidings and misdeeds in art as the spirit of Marcus Garvey’s early 20th-century Back to Africa movement; “We’ve been at the helm of a lot of movements,” Chance said. “Basquiat has got to be one of the saddest stories in the arts, period, because he died penniless and was exploited by people he considered to be his friends.

“At the Art Institute there’s a Basquiat on display by Illinois’ richest man—basically the Darth Vader of Chicago—Ken Griffin Jr.,” Chance continued. “The piece was purchased for, I think, $10 million, and that’s not money his estate got. It was from the secondary market. That’s money he never even saw when he was alive.

“The pieces that Basquiat made are all part of a conversation. I think that’s what artists do, they are in conversation with the world and responding to how the world is making them feel. And those conversations are unique to them.”

The dialogue that Chance is eliciting—live, spot-lit freestyle flubs and all—are critical to his time. At a time where The West appears embroiled in dysfunction, he has his eye on Africa. While what it means to be a Christian in America has become a live-wire question, here is a leading-edge neo-gospel artist who was a member of his school’s Jewish Student Union.

Chance has been on my mind loads since we last spoke. I think about how he offered the most minimal response of our interviews when I asked about Ye’s latest extreme difficulties. (Q: Is anyone in his circle helping Ye? Chance: I don’t know… I don’t know… ) I wonder if Chance understands that he’s not the first person, artist or civilian, to teeter on the edge of acid and find themselves religious.

None of the musings are of consequence. What is of concern? Why, that thing the painter Mia Lee told me, a week or two after YAH Know came down from MOCA’s walls. She had also attended the Art Institute event. There, Chance did not perform, but instead presented a painting from Ghanian-based artist Naila Opiangah. At one point, attendees formed a long, stylized line.

“These different places that have been the same, like museums and galleries, they’ve been the same for so long, they don’t really reflect what the world looks like now,” Lee told me on a call from England. “He’s taking institutions for art that are known for being just one thing—just the same type or art and faces and not really being included in that—and being so disruptive. You have to respect it.”

MOCA happens to be exhibiting 30 years of Henry Taylor’s painting, drawing, sculpture and installation through April. The recognition is hard-earned and long past due.

When Lee’s grandparents immigrated from Roatan—an island off the Honduras—and landed in Chicago, those Black people most likely didn’t know to dream of a painter grandchild debuting at an LA museum of MOCA’s stature. Henry Taylor, a Black artist, a local legend, might have thought such dreaming equally out of reach.

The diaspora is undeniably having a big, complicated moment in fine art. This moment of correction could not happen without disruption. Leave it to a rapper—maybe even The Rapper—to disrupt.