The University Art Museum (UAM) at California State University, Long Beach (CSULB) recently hosted artist lauren woods’ (lower case intentional, per the artist) project, American Monument 25/2018, an ongoing intermedia monument to Black lives taken by police brutality. Through most of the Fall 2018 semester controversy surrounding the work disrupted the campus, but you wouldn’t know it walking into the museum the following Spring. During a tour of the exhibition “Call and Response, When We Say… You Say,” curated —by LA-based Slanguage Studios—I asked a senior staff member about any connections between Slanguage’s institutional critiques and what happened last Fall. Her response: “What happened?”

As I share this story with woods, we break into laughter. “It’s institutional amnesia!” she responds. I continue to tell her that the tour guide, while dodging my question, intentionally noted that the inclusion of a work by Lorna Simpson, a well-known African American artist, was a curatorial decision made by the museum and not Slanguage. “It just exposes their need to mediate through art,” woods sighs.

What she refers to is the supposed neutral position art spaces, particularly large-scale publicly funded fine-arts institutions, take regarding social and political issues. As LaTanya S. Autry and Aruna D’Souza have brilliantly articulated, museums choose to embrace their function as a space to foster challenging and difficult dialogues rather than make institutional decisions that enable radical change. They “mediate” and “consider” both sides of a confrontation—and then they move on. But by choosing neutrality they choose not to challenge an oppressive structure and thus maintain it. As a visual artist, woods engages this contradiction.

lauren woods, Drinking Fountain #1, 2013

Currently based in Dallas, woods explores in her projects the impact public spaces have on social change. Her work questions the role monuments play in shaping historical narratives and social consciousness related to Black identities and experiences in the U.S. One of her first intermedia monuments, Drinking Fountain #1 (2013), took shape after a metal plate fell off the wall above a drinking fountain in the Dallas County Records Building, revealing a trace of the words “white only” from a previous sign. Woods recontextualized the fountain as an object with historical resonance. When a thirsty viewer activates the fountain it now plays a 45-second video, archival footage of Birmingham police violently using water cannons on Black civil rights activists in the 1963 desegregation campaign.

Local politicians and the Dallas public were a bit baffled. Why make people wait 45 seconds for a drink of water? Are Jim Crow laws being memorialized? Why isn’t this in a museum? We tend to correlate public monuments with memorialized historic events or people; hardly do we think of monuments as condemnations of government-sanctioned violence.

Woods believes collective authorship and ownership of public monuments plays a key role in facilitating social change rooted in equity and justice. Single works develop into large-scale collaborative projects. The Dallas Historical Parks Project (2014), for example, began as a municipal commission to reframe the history of segregated parks in Dallas. Woods and her collaborator Cynthia Mulcahy were invited to provide research and text detailing the history of those parks. However, their work—a product of intense archival research and gathered oral histories—was contested by the project’s funders. According to the funders, the artists’ texts were too much about race and complicated U.S. segregation’s traditional narrative. This led to conceptual clashes about the content, resulting in the dismissal of the artists. This public institution intended to recognize and right a disturbing history through a public-private partnership, but only on the terms set by the private parties funding the work. When those terms weren’t met, the organization tried to tell their own sanitized narrative by co-opting the artists’ labor. So, woods and Mulcahy went public. They spoke at city hall meetings and managed to pressure the funders into backing out of the project. They took action, ensuring the public had the right to access, reconstruct and tell a more complex history.

lauren woods, American Monument, 2018

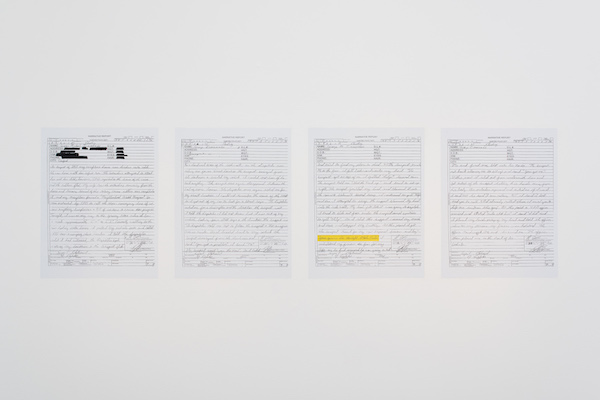

Similarly, American Monument is an exercise in collaborative art-making and collective ownership of public documents. American Monument 25/2018 transformed the museum into a monument to Black lives, people like Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, Philando Castile and as-of-now countless more, all taken by police violence. Twenty-five LPs on individual record players atop white pedestals memorialized the deaths of 25 Black women, children and men. This sound sculpture at the center of the monument held audio of their last moments taken from testimonials, witness accounts and documents, all pressed into circular acetate. Visitors could activate the work by simply dropping a needle, potentially filling the space with an overwhelming sound of violence, injustice and death.

lauren woods, American Monument, 2018

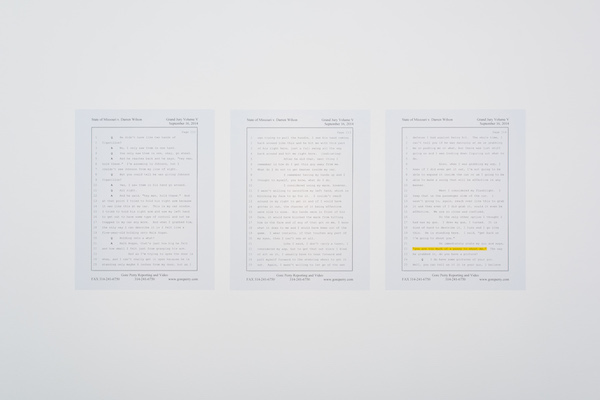

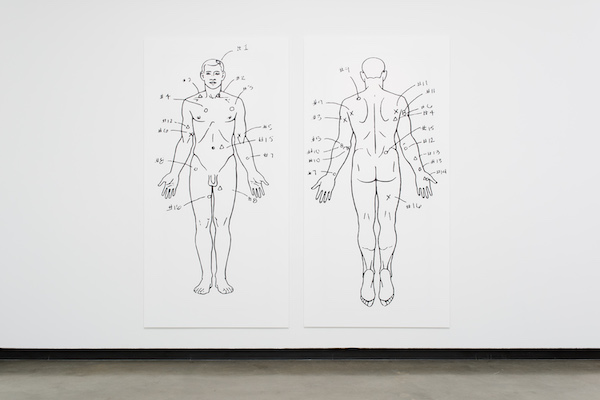

At its core, the monument holds official state documents related to these cases, painstakingly accessed through Freedom of Information Act requests by woods and collaborator and museum director Kimberli Meyer, along with a team of students. The documents provide the goverment’s narrative—a story of death, not as a result of institutionalized racism and state violence, but of highly circumstantial and isolated events. That narrative reveals a connection between culture and law. Patterns arise: police violence is repeatedly justified and rationalized, and the victims, who can no longer speak for themselves, are projected as irrational and dangerous. For example, take the official statements made by George Zimmerman, who murdered Trayvon Martin under the guise of neighborhood-watch vigilantism, and disgraced Ferguson, Missouri cop Darren Wilson, who shot and killed Michael Brown while his hands were above his head. Both murderers use African-American vernacular English when describing their victims’ supposed taunts and threats. These killers’ enlarged statements, with aforementioned “slang” highlighted, hang on opposing gallery walls, bookending a space with similar documents organized on three separate tables. Museum visitors could actively participate in the monument’s ongoing construction by examining and challenging the narratives—reclaiming ownership of public documents.

lauren woods, American Monument, 2018

Unfortunately, the monument’s participatory evolution never manifested at the UAM, at least not in the way woods envisioned. Woods paused production of the work at its opening reception in response to the abrupt firing of Meyer just days earlier. The records were removed, researched ceased and programming stopped. At the opening, woods read a statement aloud, crediting Meyer as her collaborator, and critiquing the UAM and CSULB administration for failing to recognize Meyer’s presence as important to the continuation of the work. The UAM and the university’s administration never officially stated why Meyer was fired, but professed ad nauseum that her dismissal had nothing to do with the monument’s content. Yet, as time went by, inquiries exposed questionable administrative and staff practices: The institution had demanded transcripts of the monument’s audio; CSULB wanted to involve campus police in the exhibition; Meyer was accused of not following proper administrative protocols, and admonished for attempts to ask staff to consider their race, privilege and lack of knowledge about the potential social and political concerns held by people of color regarding the monument. Some staff felt they were being asked to do things that impeded their jobs, as if these considerations made their institutional tasks harder. In the end, the optics seemed to indicate that it was easier to oust Meyer than to reflect on the problematic institutional practices that led to these tensions and act to combat them by changing policy and practice.

lauren woods, American Monument, 2018

As the monument turned into a mausoleum, critical dialogues and movements emerged within CSULB’s School of Art (SoA). Concerned students, staff and faculty interpreted Meyer’s ouster as an act of institutional violence intended to impede American Monument’s progress. Alumni, students and the SoA directors wrote public statements and press coverage followed. Students like Nicola Lee, Chris Velez and Ashley Galvan, along with alumnus Melissa Raybon created site-specific works in response to the monument’s pausing. In Raybon’s performance, What’s going on?: HOW I FEEL, the artist returned to the location where she experienced racism as a Getty intern in 2017, meditating in front of the UAM entrance for almost an hour. Faculty dedicated class time to discuss the pause. Students of color formed a strong community as they gravitated towards each other in search of a space to air grievances and organize demonstrations in solidarity with woods and Meyer. Even in its idle state, the monument propelled the public to take ownership of the narrative, stand against institutional violence and combat systemic erasure.

American Monument, like Drinking Fountain #1 and the Dallas Historical Parks Project, is an extraordinary aesthetic proposition, demanding more commitment, empathy and self-reflection than most people and institutions are used to giving to works of art and public monuments. The monument’s iteration at the UAM made abundantly clear the work and its content are not, and cannot, be isolated and contained within an art space like a traditional art object. The work lives and grows through interactions with the public—art audience or otherwise—even if it encounters resistance. All of the tensions between the parties involved fundamentally arose because an artist and cultural workers tried to address the issue of police brutality and violence against Black bodies without privileging whiteness. Marketable aesthetics, claims of reverse racism by white museum staff, the police and hypothetically from white supremacists are not primary concerns because they are not what the monument seeks to address.

lauren woods, American Monument, 2018

The second iteration of the monument will take place this year at the Beall Center for Art and Technology at University of California, Irvine (UCI). Through correspondence, Meyer shares why she and woods are continuing the work at a university art space: “Because of the rich pedagogical and research opportunities with American Monument, woods and I always felt strongly that the first iteration should be on a university campus. With the Beall and UCI as the new host, the work is benefitting from an interdisciplinary group of scholars from the School of Law and the departments of African American Studies, Social Ecology and Art. With this high level of academic collaboration, we are able to bolster the research component of the monument and build a substantial basis for it to iterate forward.” With the eyes of the public on American Monument at UCI in the near future, the relevant question will not be what happened, but rather, what will happen, and who will make it happen?