The ocean sometimes gets the best of those who love it most. The title of Alison Frey Andersson’s exhibition, “86’d” offers a surfer’s take on the hazards of that beguiling body. The Venice-based artist, who regularly succumbs to the pleasures of riding the waves on a glassed foam board, educes the essence of the sea with this show, and smartly distills the lifestyles of the ocean’s devotees into artworks that challenge the already slippery distinctions between painting, furniture and design.

Although Andersson’s objects elaborate an aesthetic of deterioration, a thread of serious painterly investigation lashes through the exhibition, oscillating between troughs of chic interior decoration and crests of raw elemental evocation. She craftily channels the her raw materials into a mergence of oceanic elementals with the stylish scrappiness of surfer habiliment.

Bailer (all works 2015) conjures thoughts of a storm surge plunging through a window; surf and curtains become one. Break Deep and Adrift recall ripped jeans and bloody bandages, respectively. These allusions to destructive oceanic power enliven her erosive investigation of painting’s boundaries.

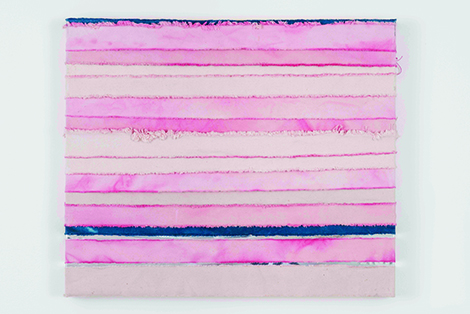

Dark Seas at Night is a nocturnal seascape contrived of indigo-dyed canvas strips stretched around a frame. Horizontal lines formed by pleats and breaches become waves. Its fibrous levelness is also reminiscent of a bedspread or pillow. With warps of canvas and wefts of twine, Sunrise and Green Flash simultaneously suggest blinded windows and radiant aqueous reflections. A Place to Sleep occupies miles of space but is least evocative, elaborating little more than a decorative rug on the wall.

Concomitant with the terrene ruggedness of her materials and her musings over the fury of the ocean, Andersson’s work provokes questions over the advancement of painting’s structures: Can a painting also be a place to sit?

Composed of blackish jean-fragments and hot pink twine stretched over steel, Volcano Chairs and Bench pause between painterly and practical. Sitting on them collapses the traditional distance between object and viewer, along with the distinction between painting and furniture. In Andersson’s hands, art objects become housewares; paintings are, at their lowest function, textiles, though they may also exist on a higher plane.

Andersson’s work is rooted squarely within painterly conventions—pigment, canvas, stretcher. Considered within the tradition of Supports/Surfaces, the 1960s–’70s French movement whose recent resurgence is spawning new strains of work investigating the possibilities and limitations of painting’s protocols, it offers new possibilities. Painters are rolling up their sleeves to surmount, rather than surrender to, the idea that “it’s been done before.”

LA painters Jennifer Boysen and Noam Rappaport are associated with this trend; but Andersson’s work is more environmentally specific. Her interest in evoking locality aligns more with New York painter Joe Fyfe’s creation of paintings from detritus salvaged from Asian travels. While questioning painting structures, Andersson and Fyfe’s environmentally specific invocations also investigate frameworks of culture external to art.

Andersson employs tropes of seaside décor to question painting’s place within domestic, artistic and environmental milieus. She weaves disparate references into California-esque tapestries of distinct flair, though her inquiries transcend locality.