The rigorous simplicity of Alice Aycock’s early architecturally-based land art, as well as the exuberant complexity and cosmological grandeur toward which she has steadily moved, were both well represented in “Alice Aycock Drawings: Some Stories are Worth Repeating,” an exhibition of Aycock’s drawings (plus photo documentation and models) on display in two Santa Barbara locations.

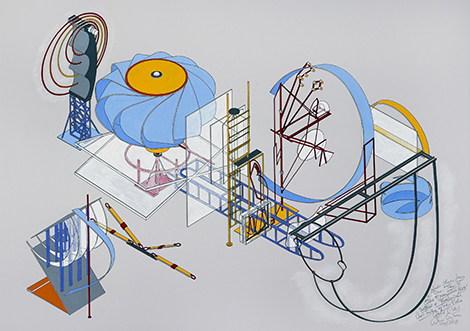

Surveying the show as a whole, two things stand out immediately. First, Aycock’s imagination has a structured expansiveness that can link the most disparate elements into coherent wholes—Middle Eastern politics and the children’s game Snakes and Ladders, for example. Second, there is a meticulous quality to her craft. Part of what brings coherence to her vision is the clarity of her drawings, which read like storyboards or diagrams of surpassing beauty and iconographic richness. In a work like Hoodo (Lara) from the series “How to Catch and Manufacture Ghosts—Vertical and Horizontal Cross-Sections of the Ether Wind” (1981), (1990/2012), we can see echoes of Duchamp’s Large Glass, especially the so-called “Glider” containing a water mill. But whereas Duchamp’s mechanical engines are slyly onanistic, Aycock’s brightly colored Hoodo evokes an ingenious (if slightly menacing) amusement park apparatus; meanwhile, the glistening steel and transparent Plexiglas of the realized sculpture conveys the look of a retro sci-fi movie set on which extraterrestrial ghosts might easily be captured or manufactured.

This is a far cry from Aycock’s earier work, like the 1975 Simple Network of Underground Wells and Tunnels. These physically arduous but simple works comprise a series of apparently useless quasi-architectural spaces, carefully fabricated from the most mundane materials (wood, concrete block), generally sunk into the ground and hence “naturalized.” Yet they still retain a rigorous architectonic organization that keeps the nature/culture distinction in play, while at the same time insuring they be seen fundamentally as artifacts within nature rather than as quasi-natural processes or interventions.

The latest work explodes into a series of studies for increasingly complex and technologically sophisticated projects, and eventually morphs into a collection of brilliant mytho-poetic exercises in cosmos-construction. Take the majestic Rock, Paper, Scissors (India, ’07) (2010). Defining the vertical thrust of the work like a slightly listing world axis is a tower that Aycock herself has identified as the Hawa Mahal, or Palace of the Winds, in Jaipur, India, where a form reminiscent of the crown of Krishna defined the interior space and which imprisoned the women of the royal harem. Turned perhaps by those palatial winds, the turbine blades embedded in a cosmological diagram (like the turbine exposed to the “ether wind” in Hoodo) drive a huge flock of tiny spinning pinwheels, exploding across the surface against an undulating red-and-white background. So, the paper of the pinwheels cut to shape by the turbine blades wraps the rock of the palace while we are all simultaneously prisoners in the tower and pinwheel-holding celebrants of Lord Krishna’s birth? Perhaps.

Or perhaps we should seek a key in a set of smaller, “simpler,” black-and white works: the series “Eaters of the Night” (1993) of which five examples appear in the show. Each individual work comprises a star diagram of the sort once published daily in The New York Times, over which have been superimposed, also in white, disconnected aspects of Aycock’s developing linear iconography. Those iconographic snippets transport us in turn to major nodes of meaning in Aycock’s self-generated cosmos: Cities, Games, Dances, Universe Schemes, Mechanical Movement, Wars. The “Eaters” are thus a kind of hinge between the simple and personal earlier work, and the complex and expansive later. Although they are no longer artifacts within nature, they are still projected upon nature, like overlays on the background of a planetarium dome.

In any case, the later work explodes that dome and transforms nature into a game board or a timescape, sweeping us off on an interstellar voyage, as in the 1988 Star Sifter: Project for Terminal One J.F.K. International Airport. In its turn the Star Sifter is then “realized” in Aycock’s 21st-century works as a kind of glowing path across what seems to be infinite time and space (Star Sifter Galaxy NGC 4314 [2005]). The JFK Airport project is not fundamentally different in its segmented circular plan from her 1972 work Maze. Taken together, these two works link the earth and the cosmos, the myth of the labyrinth and the theoretical physics of black holes and event horizons, drawing around the exhibition, as a whole, a circle of power that is at once as old as culture and as distant as the stars.