“Songbook,” Alec Soth’s current exhibition of documentary-style black-and-white environmental and ensemble portraiture at Sean Kelly Gallery is compellingly complicated in the aggregate, ultimately pointing to a deeply American dilemma of how physical and social space is negotiated. Though the photographs, when viewed individually, only hold one’s interest to varying degrees, Soth is a sincere witness, guilelessly conveying moments of turmoil or poignant impressions of personality.

At first read, his compositions seem to be straightforward portrayals of the American heartland: high school football players, girl beauty pageant contestants, cheerleaders, oil derrick workers and penitentiary guards. These characters, presented in individual portraits, pairs or cliques represent what some politicians have deceitfully called the “real America,” meaning rural as opposed to urban. Soth was born in this territory, in Minnesota among folksy folks, and for “Songbook,” he spent two years traveling around the country documenting this rustic America fading fast from the position it held at the forefront of culture in the 1950s and ’60s. These kinds of images seem, as they often have in an art context, nostalgic—though they describe contemporary lives. The people depicted represent an uncomplicated relationship between one’s identity and its constitutive components of social presentation (one’s dress), and the work one performs: the cheerleader is plainly the person who leads us in cheer. This kind of basic personal correlation has been receding since modernity divorced one’s identity from birthplace and social station. These folks simultaneously feel deeply honest and hopelessly antiquated.

Soth further draws a complex portrait of the U.S. by demonstrating the sharp contrasts of spatiality: he calls attention to the immense, open landscapes often characterized in populist narratives as wells of loneliness and sudden violence, or alternatively, to the spaces of tight, almost claustrophobic sociality. It’s either famine or feast. The lone skateboarder in Billy, Ironwood Michigan (2012) looks away from the camera, the expanse of Ironwood in the darkness closing behind him, while in Crazy Legs Saloon (2012) a Watertown, New York saloon is filled with people cavorting in a soap-filled bacchanalia. In Jesse (2012), an old man is almost swallowed up by the waist-high grass of the burial park in which he searches, while in Hunstville, Texas, a small army of police march together in Execution (2013).

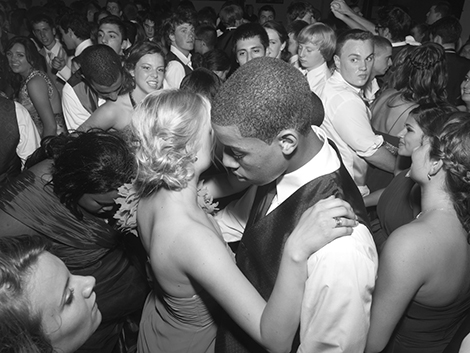

Our social interactions are particularly fraught because when we come together evincing our differences, in sexuality, in ethnicity, or otherwise, we risk rejection. In Prom #2 (2012), a gay young man looks lovingly at his date as if no one else matters; they seem at ease in a space carved out just for them. Yet, in Prom #1 (2012), the mixed-race couple—a black teen and his white girlfriend—are engulfed in a forest of envy, disgust, awe and spite.

The America reflected in these images is no more “real” than the one manifest in urban experience. However, as small town life moves slowly towards obsolescence, the elegies made to mark its passing purport to tell us we are missing something authentic and sincere.