Let me just start by applauding Liz Gordon and her team for the bravado and sheer celebration of mounting a show titled, Guns, in the current political environment. I was about to say ‘contentious’ – but there’s really nothing contentious (or new) about it. Guns are are an ineluctable aspect of American life and civilization, and, to one extent or another, an essential instrumentality of life and civilization globally. How can we not be talking about them – or for that matter be making art of and about them?

Let me just start by applauding Liz Gordon and her team for the bravado and sheer celebration of mounting a show titled, Guns, in the current political environment. I was about to say ‘contentious’ – but there’s really nothing contentious (or new) about it. Guns are are an ineluctable aspect of American life and civilization, and, to one extent or another, an essential instrumentality of life and civilization globally. How can we not be talking about them – or for that matter be making art of and about them?

Cheryl Dullabaun, “Sure Shot (ii)”

My understanding is that Liz and Betty Ann Brown had been discussing this show for some time before it was actually scheduled and that no one had any idea how ‘yuuuugge’ gun issues would be blowing up (well…) about now. But let’s face it, this is not something that is ever far away. Somewhere on your block is someone with a gun. Maybe guns. Or in your building. We can’t live without them – although some of us (e.g., me) can’t live with them, either (which makes me one of the freaks – gee what else is new?). We lean a bit on our gun-toting fellow citizens; and they know it and we know it, which is why we try to amuse them and keep their minds off their lethal, uh, resolution facilitators.

I get (got?) the Second Amendment. It is essential to the ‘democracy’ component of our constitutional ‘democratic republic’ (not going to get into other legal issues here), second only to the First Amendment (and naturally followed by those specifically ‘legal’ ones – the Fifth and Sixth). Why? Because, like the First, it directly acknowledges and addresses our humanity and, well, equality – and the instruments by which we move the scales closer to that egalitarian ideal, or at least some acceptable median. With the gun (or similarly effective weapon), the peasant can kill the king. Sure, we can mock the king, denounce the king, embarrass the king, and incriminate him (and it’s usually a him); but the gun shifts the needle. Long live the new king – or peasant (although the peasant most likely dies, too; gravity will not be denied). We don’t call it the great equalizer for nothing.

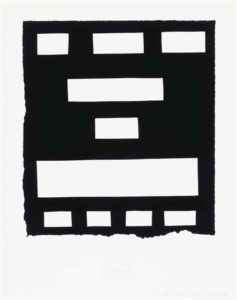

Ed Ruscha, “I Have Not Forgotten,” 2007

We’ve always been fascinated by and covetous of guns and firearms, ballistics, and weapons (including projectile and edge-type) generally. Guns and firearms are actually direct descendants of projectile weapons – flaming arrows, and more specifically, fire lances, which used a prototype gunpowder to accelerate propulsion. (Which gets us into our fascination with magic powders – but that’s another subject.) There was art in the making of these instruments and art to be made of them. LACMA’s collection is not particularly notable for its collections of armour and weaponry; but the Met’s collection is positively staggering, and I can remember being fascinated by it as a child. (LACMA hosted an exhibition of samourai armour only a year or so ago.)

(No, this wasn’t part of the LACMA exhibition — but what a samourai!)

Humans, like other large predators, are inclined to kill; and with our surging populations, it could almost be said that we kill with every breath we take. Amongst this most predatory species on earth, Americans are the super-predators. We’re not alone in killing for sport, in our cruelty and viciousness. But we tend to be pretty shameless about rationalizing or excusing it, or inventing fictitious theories of causality to explain or justify it. And we just love our guns to death.

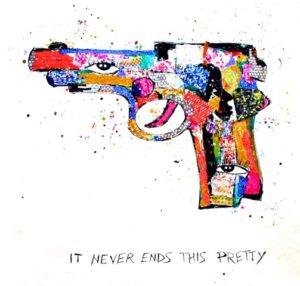

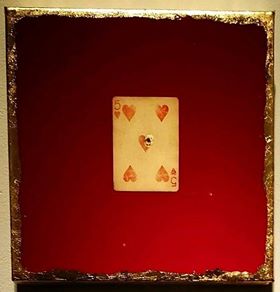

So why not a show celebrating them? And why not share it with Artillery readers (though I am away without official leave quite frequently)? There are more than 20 artists in this show, which is a bit crowded; and I almost expected the show to thin itself out with gunfire sound effects signalling the elimination of the weaker specimens; but when I left (although one of the best was marked sold), most were right where I saw them. I thought Cheryl Dullabaun’s Sure Shot (iv) – with its gold leaf heart pierced by a bullet-hole in its center, set squarely in a field of velvety (blood?) red edged by gold, went right to the, uh, heart of the matter; and her other ‘gunshot’ pieces had a similar craftsman-like charm. Clayton Campbell’s digital photograph, Clean Hit on an Easy Soft Target (2016), with its assassin’s gun trained on an unsuspecting traveler’s back, from his series, The 1% War, was probably the most forward-looking. But then, as Harry Lime (Orson Welles) pointed out in Carol Reed’s The Third Man, the Renaissance was a pretty violent time, too (to say nothing of the insanely bloody violence that ushered in L.A.’s early industrial history). Ed Ruscha is represented here with a few of his (Gemini-published) dry but mordant ‘cut-out/redaction’ hold-up/ransom lithographs. Helen Chung made a lovely ‘Kalashnikov-koffin’ (RIP) that would have made a great housewarming gift for Marcel Duchamp; and I could appreciate the quiet economy of Jane Goren’s Cold Dead Hands with its lighted handguns. Joyce Dallal’s Fun Guns amounted cumulatively to another inventory; but more is not always more, especially where guns are concerned. The viewer needs more fun for his/her gun.

Michael Flechtner, “Shotgun Shack: Living the Amerian Dream,” 2016

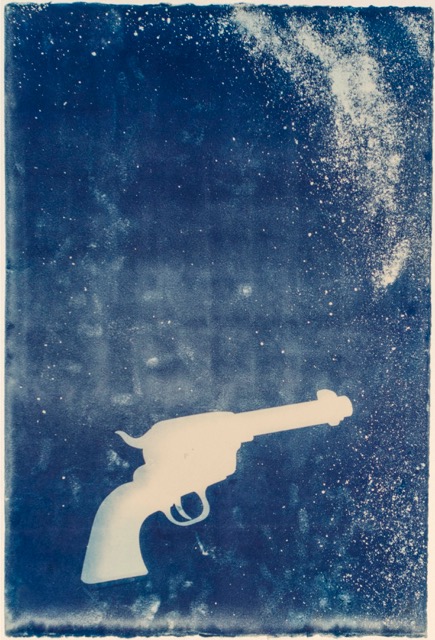

It’s hard not to get a bit jaded around the subject. I mean – it’s an everyday experience today. Children – even fairly affluent children – go to school not entirely sure whether they’ll have two, one or no parents at all to come home to. Even children not traumatized by violence before puberty – increasingly a minority in our violent, globally war-ravaged, terrorized, gun-crazy, open-carry, increasingly chaotic societies – are fairly inured to representations of guns and gun violence. Ted Meyer’s Suburban Killer Barbie would have probably elicited little more than an ironic smile from my nieces and nephews before they were even six. I tend to appreciate the more straightforward and matter-of-fact renderings. In that regard, the gun can be a pretty blunt instrument; it implicitly puts a lot of silence around it – which in visual terms, usually means space. Meg Madison’s cyanotypes were eloquent in their quiet floating echoes of our weapon obsession. Other notable artists here include Mark Steven Greenfield, Shepard Fairey, and Michael Flechtner, whose gorgeous animated neon Shotgun Shack: Living the American Dream (2016) pretty much summed it up. It Never Ends This Pretty, as Miles Regis points out in his 2016 acrylic (and sequinned!) gun on canvas – and it’s usually, as I think Racine put it, pretty bloody in the end, too; but at least their aim is true.