Adrian Piper’s retrospective was the largest solo show dedicated to a living American artist MoMA has ever produced, and though its Hammer iteration is a tad smaller, it’s no less of a triumph. A mixture of reams of text, performance, posters, newspaper ads, photos, didactics, theatrical installations, music, and giveaway ephemera, it’s one of the densest collections of work by a single artist I’ve ever encountered, and I doubt there’s enough time for any visitor to absorb the whole thing. I’ve been a fan of Piper’s work ever since I saw her mid-career show at LA’s MOCA back in 2000. She’s always been a badass, making some of the best, most devastatingly poignant work addressing race, gender, and political agency. But this retrospective seems to establish her life-long project as one exploring shared humanity.

The installation moves chronologically starting with work executed when Piper was a teenager. Except for her haunting combine painting, Barbara Epstein and Doll (1966), her nascent paintings and drawings—a series of discombobulated dolls and a collection of trippy paintings, some of which were made under the influence of LSD—seem out of place considering the artist’s lifelong conceptual art credentials. They don’t impress in isolation, but do foreshadow Piper’s later explorations into embodied subjects, imagined others, and faulty perceptions.

While the exhibition provides visitors with a wealth of the artist’s early conceptual work, including exhaustive text pieces, schematics, and process-based projects encased in vitrines, it’s her move towards performance that moves the show along. In her Catalysis series from 1970, the artist makes her body strange, walking around New York City with a ball of fabric bulging from her mouth, or wearing a sandwich board bearing the words “WET PAINT.” Photographic documentation captures the moments when her performances activate the self-consciousness of the people she encounters, the moment they might be aware of their own looking, their body’s proximity to hers, the moments that prick the porous boundaries of normalcy.

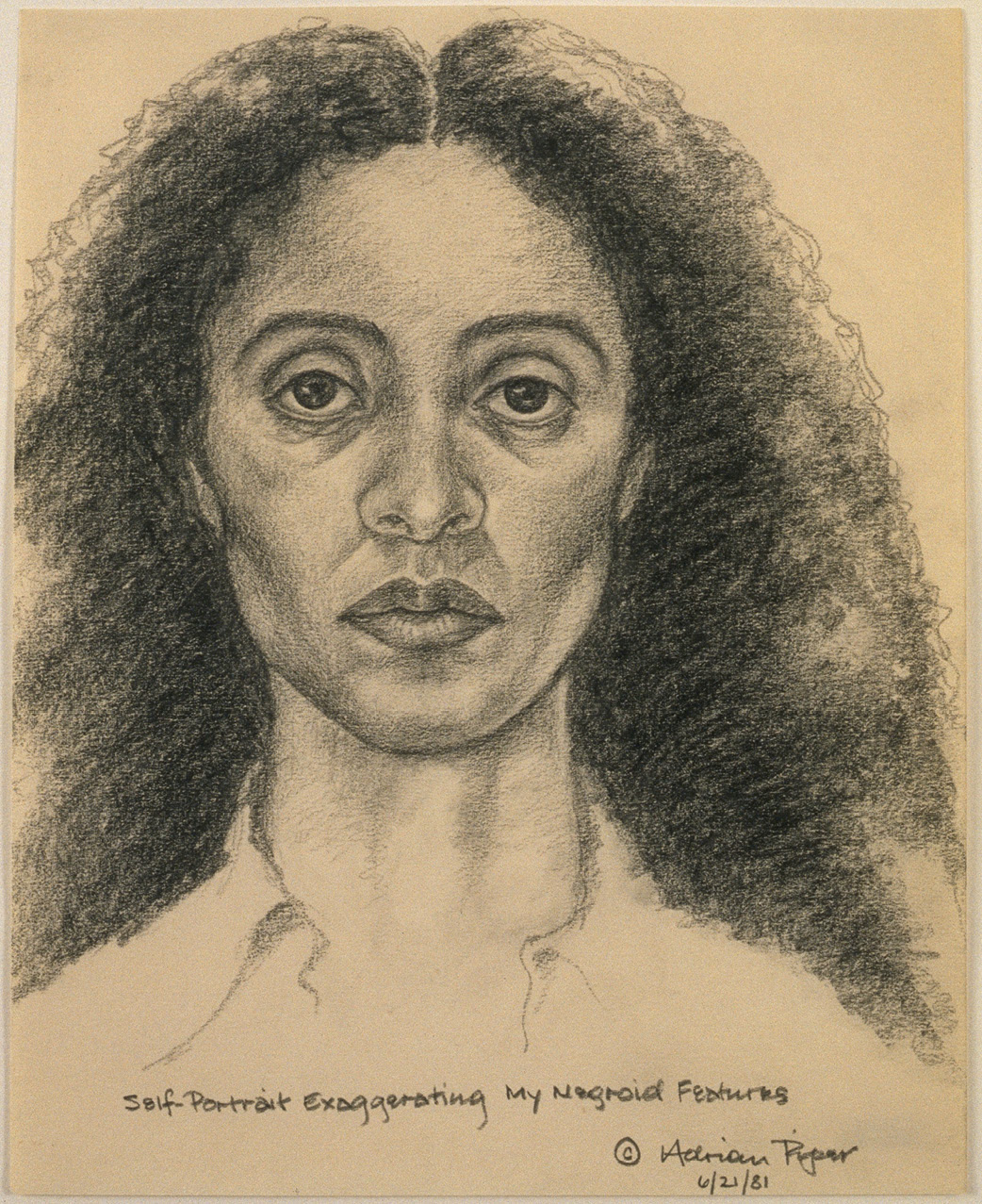

Adrian Piper, Self-Portrait Exaggerating My Negroid Features (1981), The Eileen Harris Norton Collection © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin

In other instances, Piper makes viewers aware of their own inner monologues when encountering the difficult and unfamiliar. In Art for the Art World Surface Pattern from 1976 she presents viewers with a room about the size of a closet, its insides covered in custom wallpaper made of images of war, exploitation, consumerism, and international accounts of leftist resistance, obscured at points with the words “NOT A PERFORMANCE.” An audio track plays snide remarks about an aversion to overtly political imagery in art, pointing out that this kind of art doesn’t “belong.” The presence of this disembodied voice anticipates possible knee-jerk disregard from the actual viewer, demanding consideration of the biases, detached complicity, and expectations one brings to politics AND aesthetic “taste.”

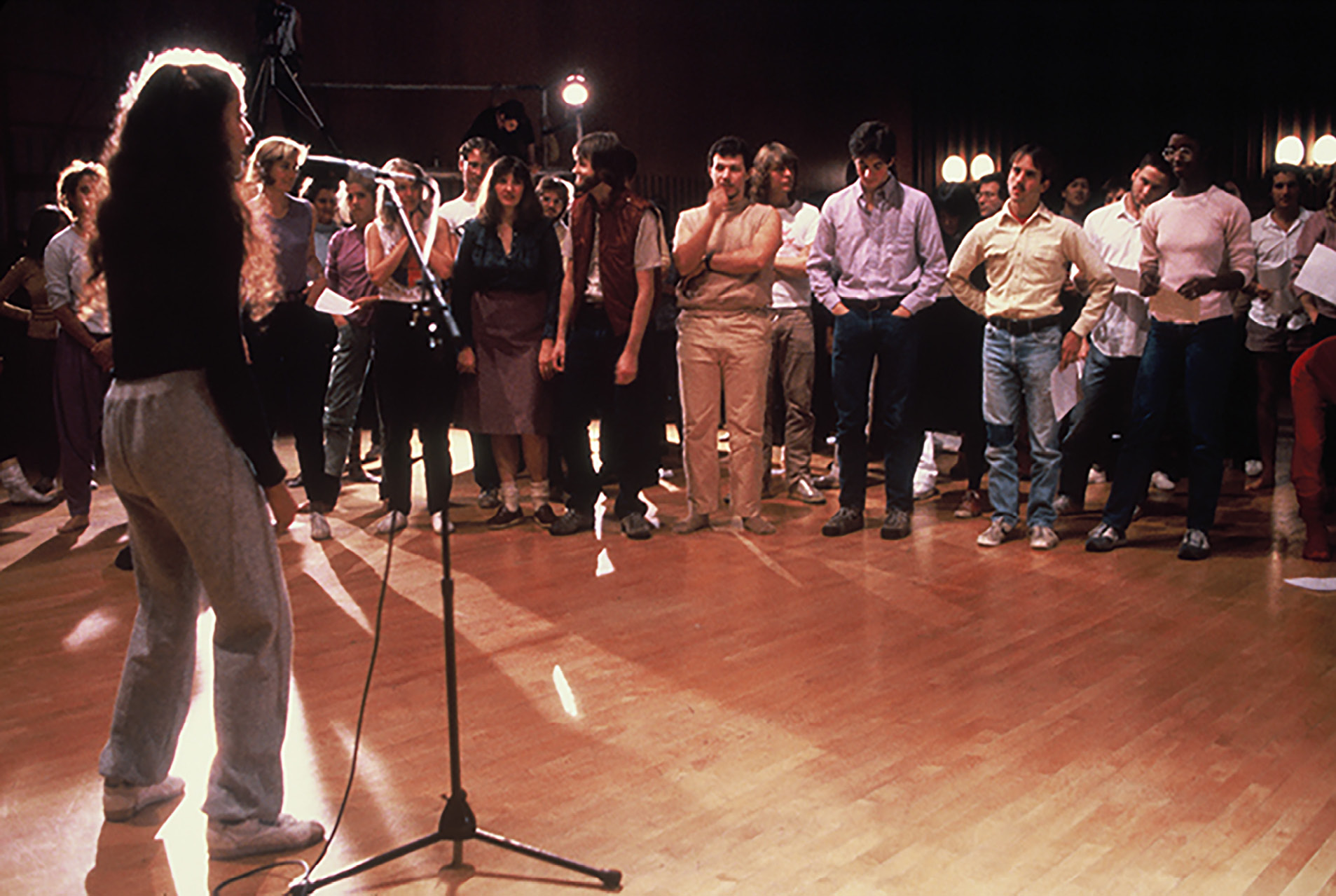

Much more entertaining, but no less critical, Funk Lessons from 1983-84 proves one of the exhibition’s most memorable pieces. In this video, Piper leads an instructional class about the history of funk music and the ways one can dance to it. Acting in a professorial manner, she instructs a group of young, mostly—but certainly not entirely—“white” college students in the art of head nodding, hip thrusting, and generally getting down. The video cuts from this sweaty, gyrating classroom to footage of people dancing on TV shows, interviews with participants, all while periodic statements linking ideas of race to dancing appear at the bottom of the screen. The artist’s commentary on the unique syncopation that makes funk special and observations about how dancing brings people together are juxtaposed with her thoughts about the genre’s appropriation by superstar musicians like The Rolling Stones who reap the financial benefits of their progenitors’ innovations while rarely sharing the credit (or the money).

“tissue boxes and trash baskets” are materials listed in Piper’s Black Box/White Box installation from 1992. These two rooms punctuate an important turning point in the exhibition. Black Box contains a chair beneath an image of George H. W. Bush glad-handing a gang of LAPD officers. Seated in the chair, the viewer sees a back-lit photograph of Rodney King’s beaten and bruised face while speakers play King’s “Can’t we all just get along?” public address. Suddenly, a light illuminates the room, and the photo becomes a mirror reflecting the viewer, creating a moment of inescapable self-reflection. White Box has a similar set up: a chair faces a monitor playing the Rodney King beating video on a loop, accompanied by Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On? When I experienced this work, I looked at the trash bin of used tissues and struggled to remember ever encountering an artwork that rightfully anticipated its audience’s tears. A quote by Alexander Solzhenitsyn appears on the interior walls in each box reading, “Once you have taken everything from a man, he is no longer in your power. He is free.” The underlying message asks who gets to take, who has the power, who will be free, and what you’re willing to lose.

Reflections of loss and impermanence punctuate the rest of Piper’s more recent works, which repeatedly contain the phrase “Everything will be taken away.” typed on photos and stenciled on reflective surfaces. The box of tissue makes yet another appearance in You/Stop/Watch: A Shiva Japam, a video from 2002 where Piper recites a mantra intended to prepare one for death. Maybe I’m wrong, but her tears seem genuine; in the end there’s no performance, only the fact that one day, for all of us, everything will be taken away.