“Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West” is a new exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art in Hawaii seeking to revisit and, in effect, rewrite the history of Abstract Expressionism. Since AbEx debuted in the 1940s, the movement has been lauded by critics. Yet, this first uniquely American art movement to achieve international recognition has never fully taken into account its female practitioners or those practicing outside of New York City—the movement’s de facto capital—effectively reducing them to second-tier status.

“Looking East” redresses those lapses by presenting work of masters like Pollock, de Kooning, and Rothko alongside their lesser recognized contemporaries, including painters Paul Horiuchi and Kenzo Okada, sculptors Ruth Asawa and Isamu Noguchi, and artists of Hawaii such as Satoru Abe, Bumpei Akaji, Isami Doi, Ralph Iwamoto, Tadashi Sato and others. With more than 45 illustrations, paintings, and sculptures, the show explores the ways Asian-American and Hawaii practitioners shaped Abstract Expressionism with influences from Zen Buddhism to the gestural lyricism of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy.

Installation view, “Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West,” Honolulu Museum of Art.

“It’s hard to say new things about Abstract Expressionism, so the fact that we’re adding to the story is important,” says Honolulu Museum Director Sean O’Harrow. “We’re bolstering history to make it more complete because the traditional narrative has been edited heavily. Hawaii played a unique role as well.”

It was especially difficult for Asian-American artists creating works of AbEx to break into the movement. They were often either expected to incorporate “Asian” qualities in their paintings or sculpture—or conversely were criticized for creating “Western” art from an Asian stance. Many also experimented with technique and approach, while the New York School artists instead each stuck to a particular signature style.

Isamu Noguchi,Victim, 1962, cast 1984, ©2017 The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, New York/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“So for someone like Isamu Noguchi, who is Japanese-American and a sculptor and working in several different mediums, not just one definitive style; these artists get marginalized very fast and sidelined in the media,” says Honolulu Museum Curator of European and American Art Theresa Papanikolas, who curated “Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West.”

Noguchi, also a designer, was born in Los Angeles to a Japanese poet and an American writer. He studied medicine at Columbia University and sculpture at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School in New York City, assisted modernist Constantin Brâncusi in Paris, and learned Zen simplicity and pottery in Japan. His work ranged from public art installations to home furniture and merged abstract modernism with traditionalism, fusing geometric and organic forms.

“There are a lot of stories being spun that sort of hype up the independence and ‘singular genius’ of [Abstract Expressionism] artists,” O’Harrow says. “There’s still this idea that the artists in New York weren’t influenced by Asian artists, which I don’t find very credible.”

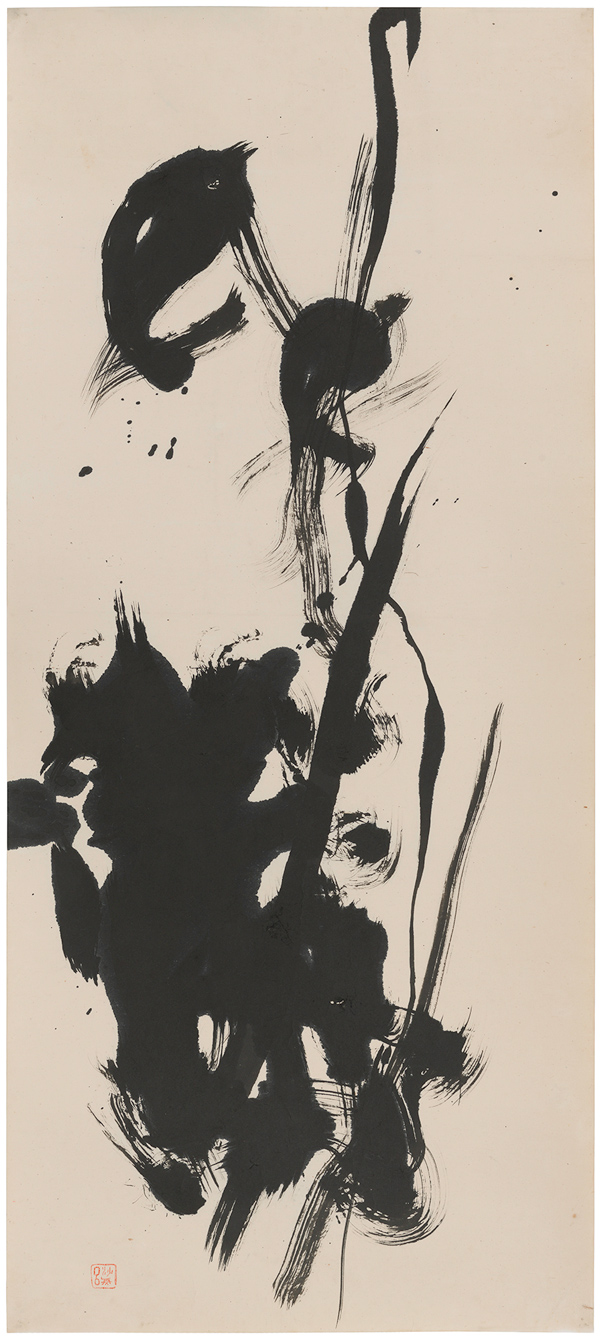

Saburo Hasegawa, Abstract Calligraphy, c. 1955–7. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Joseph Brotherton. © Estate of Saburo Hasegawa. Photograph: Don Ross.

Consider the painter and calligrapher Saburo Hasegawa. Born and raised in Japan, he studied Italian Renaissance art in Paris and later taught Zen philosophy in New York City and San Francisco. His black-and-white compositions combined European abstract art with the gestural style of Japanese calligraphy.

Hasegawa lectured regularly at the Eighth Street Club; from 1950 to 1960, this was a gathering place for artists, intellectuals, and creatives such as Guston, de Kooning, Kline, and Pollock. During regular Friday night panel discussions, topics ranged from existentialism to Freud, Marxism, and modern art. An entire series was dedicated to Japanese art, which was of particular interest to the New York School artists. They recognized Zen as a valuable tool; the ability to clear the mind, cast out preconceived notions about art theory and traditional ideas, and maintain a natural inner calm would allow for maximum spontaneity on the canvas.

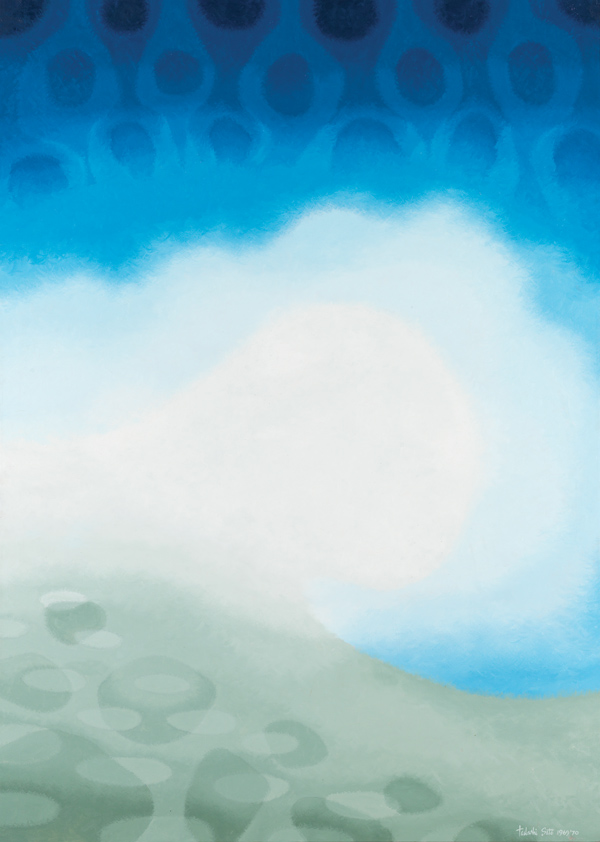

Tadashi Sato, Surf and Water Reflections, 1969‒70. Honolulu Museum of Art, Gift of The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, 2011, and gift of the Honolulu Advertiser Collection at Persis Corporation, 1974

Hawaii-born artist Tadashi Sato often created paintings and murals of lush blue and green scenes, evoking a sensation of water and the natural world. In Surf and Water Reflections (1969–70), a bright spherical center is cradled above and below by what could be a blue ocean and green land. Yet within the blue is a loose pattern of plant pods and amidst the green, oblong shapes that mirror the glossy surface of water.

Reflections is presented in the exhibition alongside Falling Leaf (1966), a monochromatic painting which depicts a feather-like leaf hovering between light circular patterns below and a looming dark sphere above. Sato’s daughter, Janice, remembers her father watching television coverage of the Kennedy assassination in 1963 when a leaf fell outside their living room window. The artist took it as a sign, which inspired the work.

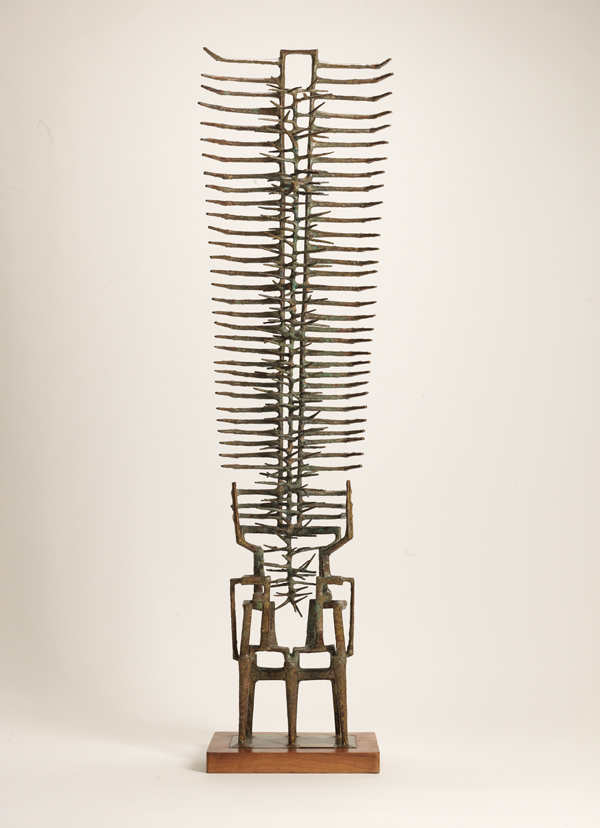

Satoru Abe, The Idol, 1958, welded copper and bronze, Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Keiji Kawakami Art Foundation Fund, 1992, ©2017 Satoru Abe.

Elsewhere in the exhibition, next to a black-and-white abstract calligraphy ink painting by Hasegawa and an untitled piece by Robert Motherwell featuring an oil paint–splash “wave” cresting through the air, Asian-American AbEx artist Satoru Abe presents The Idol (1958), an equally delicate copper and bronze skeletal monument. Abe’s sculptures are simultaneously rigid yet seemingly fluid, organic interwoven structures that create a sense of flux.

Abe originally traveled by ship from Hawaii to the mainland to study at the Art Students League of New York in the late 1940s. Working as a restaurant dishwasher making 75 cents an hour, he began welding and learned the basics by experimenting with sanding and melting. At the time, art was limited to just painting and sculpture. “Ceramics was considered a craft. And photography wasn’t included. Today, everything is art,” says Abe. “Which is very good. I would say that anything man-made has merit. The only criteria is well done or not well done.

In 1950 he returned to Hawaii, where he connected with other local artists also returning to the Islands: Sato from Pratt Institute, painter Tetsuo Ochikubo from the Chicago Art Museum, sculptor Bumpei Akaji, who served in the all-Japanese 442nd Infantry regiment during WWII, and painter and printmaker Isami Doi, who became a mentor. The group, together with other fellow Hawaii modernist artists, became known as the “Metcalf Chateau,” named after a house on Metcalf Street that Abe and Akaji rented for six months and where the group exhibited artwork. After their first show in 1954, the exhibit was moved to what is now the Honolulu Museum of Art.

More than 60 years later, the Asian-American artists have returned to the museum for “Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West,” where their art can take its place next to works by Pollock, de Kooning, and Rothko—filling out the history of Abstract Expressionism with vivid evidence of their impact on the movement.

Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West runs through January 21, 2018, at the Honolulu Museum of Art. For more info, visit http://honolulu

museum.org/art/exhibitions.