This summer we’ve had the extraordinary opportunity to time travel, and see the work of two artists, generations apart but both deeply moved by a need to reflect on the history of racial discrimination in this country. Through their work and careers, we see how times have changed, yet also how underlying dynamics have remained the same, sadly. A survey of the work of Noah Purifoy, “Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada,” opened June 7 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (through Sept. 27), and recent works by Mark Bradford, “Mark Bradford: Scorched Earth,” opened June 20 at the Hammer Museum (also through Sept. 27).

Both feature artists who are gifted originals in their approach to art-making. Purifoy is known for his outdoor constructions and installations on 10 acres of desert in Joshua Tree, the Outdoor Museum. However, the LACMA exhibition features his less-known studio work, which like the outdoor works are inventive reworkings of the cast-offs and detritus of modern life, plus a few pieces brought from the desert. Old planks, bowling balls, bicycles, and appliances are among his raw materials. The show ranges from 1958 to the end of his career—Purifoy spent the last 15 years of his life in Joshua Tree and died in 2004.

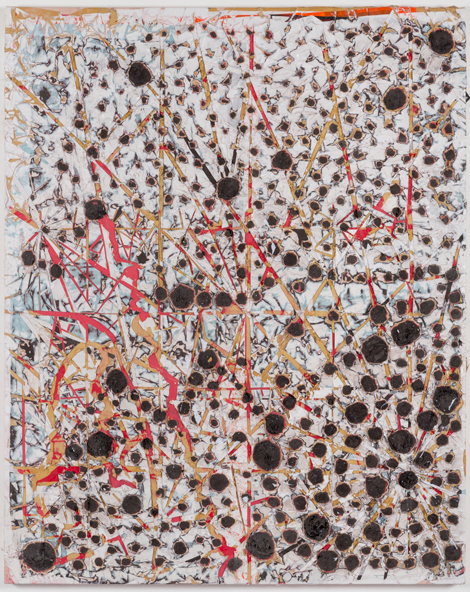

Mark Bradford,Test 3, 2015. Mixed media on canvas. 62 x 48 in., Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Joshua White.

Mark Bradford is one of LA’s brightest art stars, and his work at the Hammer occupies the atrium wall with a map of the U.S. overlaid with numbers indicating AIDS deaths, plus three galleries upstairs. While there was almost too much literalness in his earlier works, his new works are both beautiful—yes, beautiful—and also profoundly transcendent.

Purifoy and Bradford are African American, and both received formal training at art schools. Purifoy attended the Chouinard Art Institute, and Bradford has a BFA and an MFA from Cal Arts. (So actually they studied at the same school as Chouinard became CalArts.) Their imagination and aesthetics were fired in two LA riots. Born in 1917, Purifoy was raised in the segregated South—Alabama, no less. Moving to LA in 1950, he graduated from Chouinard in 1956. In 1964 he helped found the Watts Towers Art Center, and a year later he was witness to the Watts Riots, or the Watts Rebellion, which he thought long overdue given the racist conditions of the city. In its aftermath, Purifoy and fellow artist Judson Powell went into the streets to collect charred debris and melted neon signs to turn into art. With six other artists, they used the material to make sculpture, creating an exhibition— “66 Signs of Neon”—which toured nationally. (Several of Purifoy’s works from that show are in the LACMA show, which has been co-curated by Franklin Sirmans and Yael Lipschutz.) Some works even went to Germany under the auspices of the U.S. Information Agency, which was interested in demonstrating the freedom and power of “the American Way” to postwar Europe. There Purifoy was shown with John Chamberlain, Ed Kienholz and Robert Rauschenberg.

An art career is not an easy one: Purifoy worked in public service and even abandoned art for a while before returning to it in 1987 when he was 70. This is in stark contrast to Mark Bradford, whose art career has gone from strength to strength since leaving art school and who is now represented by powerhouse dealer Hauser & Wirth. This May his recent painting Smear was auctioned off by Sotheby’s for a stunning $4.39 million—a record for an LA-based artist. (The proceeds were donated to MOCA LA.)

Purifoy finally moved to the desert in 1989—living on Social Security, he was offered a place to live and work by his friend Debbie Brewer. As we see from this exhibition, Purifoy did not forget his political connections. In Sir Watts II (1996) he reflects on the Watts Rebellion: a metal body topped with what looks like a Kaiser German helmet, with an opening in the chest revealing a circuit board beneath. In Strange Fruit (2002), a cloud of white feathers float on the black surface of a canvas, with an actual bucket of paint and paintbrush hanging from the lower edge. It’s a reference to the tarring and feathering of African Americans in times past, and with the title taken from the haunting Billie Holliday song, with the lyrics, “Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze/ Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.”

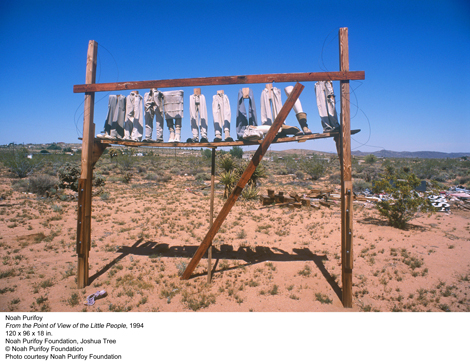

Two galleries at the end of the show feature several large works temporarily brought in from the Outdoor Museum. From the Point of View of the Little People (1994) is probably Purifoy’s most famous construction, often reproduced. It is certainly one of his most poignant and beautiful—a row of weathered jeans, boy-sized, are “standing” over sneakers and placed in a row on an elevated scaffolding. This might be a reference to lynching, though I think it is also a portrait of fragile adolescence through jeans and sneakers. Purifoy was certainly not only preoccupied with race, he was also thoughtful about the human condition, formalist considerations and entropy. Here the desert climate has collaborated with Purifoy to add to the impact of his art, as the jeans have faded and gotten tattered, and the desiccated shoes turn up at the toes.

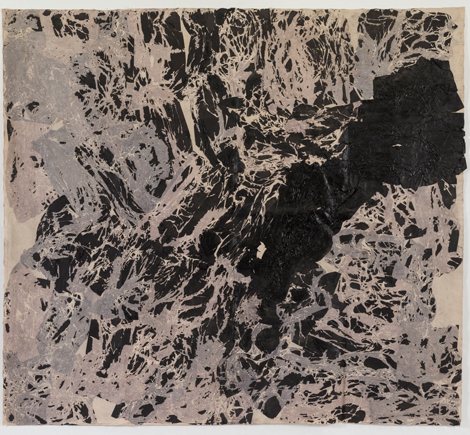

Mark Bradford, Untitled, 2015. Mixed media on canvas. 144 x 144 in. (365.8 x 365.8 cm). Courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo by Joshua White.

Bradford was born in 1961; he grew up in South Central and still maintains a studio in that area. He was at his Leimert Park studio during the 1992 riots that took place in the aftermath of the Rodney King beating by LA police. As the exhibition says, the event was a “touchstone for Bradford… The outrage that boiled over, fueled by decades of social and economic disenfranchisement, shadowed the fury that engulfed the area during the Watts Rebellion in 1965.” In a recent conversation with Anita Hill at the Hammer—a truly fascinating one about race, exclusion and inclusion—Bradford said, “I like to call them RIOTS, not civil unrest. You don’t cool off things that should stay hot.”

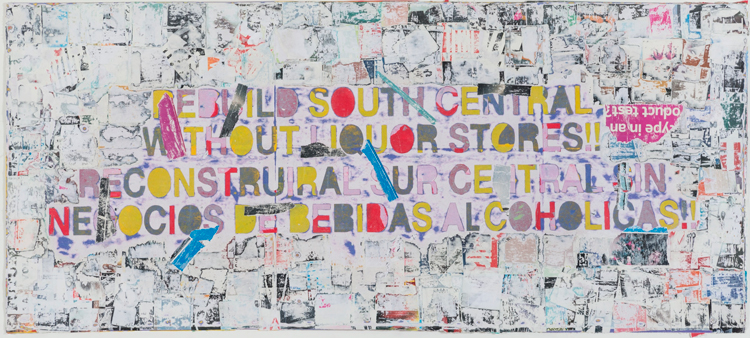

The first work that hits you as you enter the Hammer exhibition, curated by Connie Butler and Jamillah James, is the only one with words—on a background of built-up layers of paper are lines of colorful block print. The first line reads “REBUILD SOUTH CENTRAL,” and is taken from a banner Bradford saw in a photograph after the riots. Further on, a series which includes Dead Hummingbird, Lights and Tunnels and The Next Hot Line invokes maps and urbanscapes, but they look slashed and gouged.

Bradford’s process is multi-stepped. He usually begins by applying layers and layers of paper to canvas—the papers themselves sometimes colored or printed—and shellacking between the layers. Into the layers he may add paint, string and caulking, sometime balls of paper; then he sands and gouges to excavate the final work. Even though most of the work is abstract, there is palpable political consciousness here. Another grouping of three, as he said in a recent New Yorker article, “They’re all based on AIDS cells under a microscope. I don’t want to say the show is about AIDS, but it’s about the body, and about my relationship to the 1980s, when all that stuff hit. It’s my using a particular moment and abstracting it.” With its surface scored by red and black lines, the “Sample” series conjures up connective tissue and diseased cells, and a condition that has affected many gay men of his generation.

This artist has had the good fortune to be recognized in his lifetime, both in commercial galleries and in museums. He’s also been trying to build community in South Central through Art + Practice, a foundation he co-founded with his life partner Allan DiCastro and philanthropist/art collector Eileen Harris Norton. While in another part of town, someone under-appreciated in his lifetime is enjoying a major museum survey posthumously. As curator Yael Lipschutz has said, “Noah would have been thrilled, absolutely thrilled, to be showing at LACMA.”