Monument Lab, based in Philadelphia, and founded by curator Paul Farber and artist Ken Lum, is a public art and history studio whose moment has arrived. Defining monuments as “a statement of power and presence in public” they’ve intersected with the active national movement to remove monuments and statues that reflect the racist history of the United States. Their values reflect progressive antiracist, de-colonial, feminist, queer, working class, ecological, and social justice perspectives working to inform our understandings of U.S. history and its monuments. In just a few years they have expanded from local projects to having a national and international profile. They just received a $4 million grant as part of Mellon Foundation’s $250 million Monuments Project. Monument Lab’s grant will support the production of a definitive audit of the nation’s monuments. This will help identify the stories and narratives that have been ignored and do not exist in monument or memorial form. They will be opening ten field research offices, one of those offices may be in Los Angeles next year.

This past year has stretched our capacity to imagine what comes next, with the confluence of the pandemic, a heightened movement for racial justice, and an election with its caustic aftermath. Throughout we have seen offending statues and monuments pulled down around the United States as well as Europe. Questions are unresolved about how to contextualize these faded, flawed icons. While some want to see problematic statues reflective of our racist past disappear, others would prefer for them to stay, so long as placards and descriptive texts that contextualize and educate the public surround them. Beyond this however, how do we then begin to memorialize our country’s many ignored and suppressed histories in their place?

Ken Lum is the Artistic Director of Monument Lab, but also a prolific Canadian visual artist, writer, and teacher of Chinese descent. He has produced numerous powerful public works challenging established worldviews about how we see ourselves. Artist Hans Haacke says of Ken, “ Over many decades he has pointedly challenged ruling classes in many regions of the world, religious suppression, racism and other horrors. Driven by a deep sense of humanity, his engagement, backed by a wide knowledge of history and pertinent literature, is reflected in his thoughtful writings on art and life.”

Next year Ken will be having an exhibition at Royale Projects in Los Angeles. His new works are photo-based images screen-printed onto mirrors. They make a strong commentary about bias in our popular imagination, cultural legacy and received histories. At sizes up to 6 by 6 feet, works like Anna May Wong, Batista, or United States at Night, cover a range of his social justice concerns by looking at Asian American stereotypes, U.S. foreign interventions, and climate change.

Ken Lum, Anna May Wong, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020

Ken Lum, Batista, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020

Ken Lum, United States at Night, screen print on mirror, 6’ x 6’, 2020

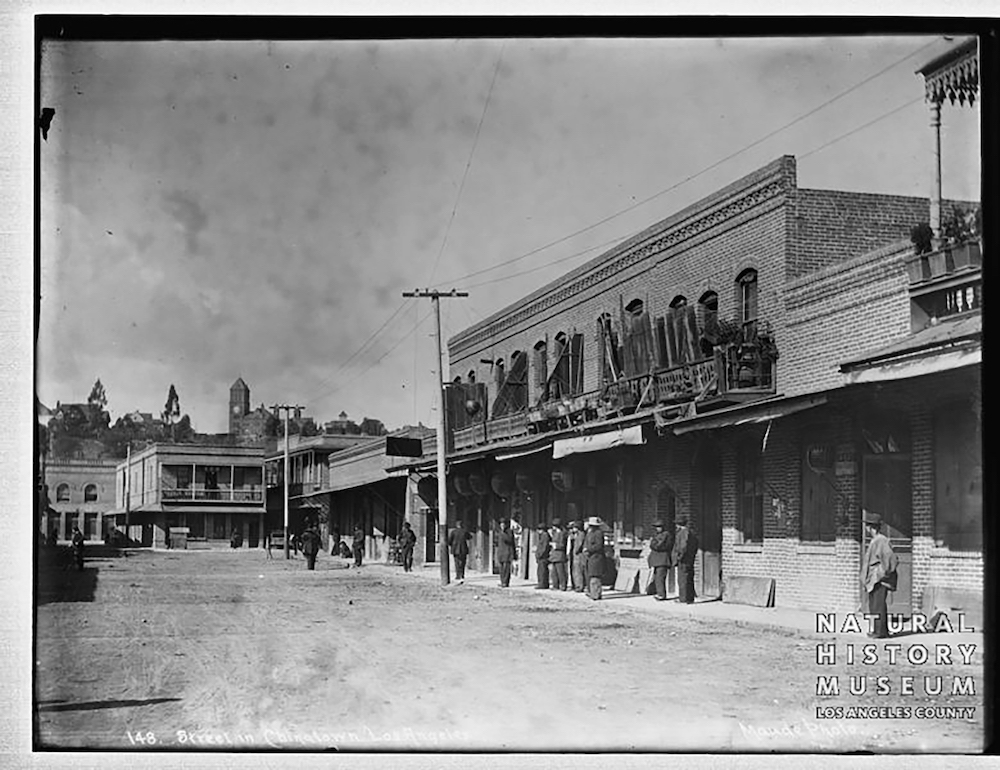

I asked Ken what public art commission he would like to do in Los Angeles if asked. His response was immediate. “The Chinese Massacre. Do you know about it?” I did, in fact, know a little bit because there is a plaque about it in the sidewalk in front of the Chinese American Museum on Los Angeles Street in downtown LA. What I didn’t know was that Los Angeles Street was the original location of Chinatown in what had been named ‘Negro Alley’ after the dark skinned Spaniards who first lived there. It was also the red light saloon district where Chinese had been segregated to live. The plaque is all that marks the site of what is known as one of the worst mass lynchings in US history, a part of Los Angeles’ history. It corresponded with the rise of Nativism, as anti-immigrant hostilities boiled over in 1871 when a mob of Anglo and Hispanic people attacked, robbed, and hung 17 Chinese. This history was more or less erased when Chinatown was moved to its new location in 1938. The site of the massacre is now an off ramp of the 101 Freeway. Not long after the massacre the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed to maintain white “racial purity” and placate complaints that the Chinese were taking jobs. They comprised .002% of the population at the time. Why does this refrain sound all too familiar today? Over and over again Los Angeles has been an epicenter of anti-immigrant hostility, racism towards people of color, and the erasure of indigenous people. With dysfunctional immigration and homeless policies, we are in the midst of yet another chapter of a long and tortured history of abuse and neglect.

Chinese Massacre site, 1871, Los Angeles Historical Society archives

In speaking with Paul Farber, who is a scholar, curator, and the Director of Monument Lab, one gets a clear sense of an organization driven by passion and forward movement. They have had numerous projects, and in particular Shaping the Past has been significant. The project facilitates a transnational exchange program bringing artists and activists together in dialogue to highlight ongoing critical memory interventions in sites and spaces in North America and Germany. It supports civic practitioners, artists, and activists who critically reimagine monuments and emerges from the ongoing Monument Lab Fellows program. These collaborations and conversations are seeking to offer innovative models for how we might memorialize the past, create dialogue, and strengthen democracy through public spaces across the globe.

https://monumentlab.com/projects/shaping-the-past

I wondered what happened after an offending monument comes down. When a statue is pulled off of its pedestal, does the question of what to put in a newly vacant town plaza become important to that site and community? Do we find meaning in leaving something behind, some kind of marker, or is it better to leave nothing at all?

Paul visited a site in Richmond, Virginia, where Gabriel Prosser, an enslaved blacksmith, was hanged after a failed rebellion in 1800. In a New Yorker article by Hua Hsu from September 15, 2020, Paul said, “When I arrived, I was deeply moved. I have visited numerous cities where empty pedestals were removed or cut off from public activity. In hindsight, it was a mistake to try to erase struggle. The deeper harms of racism were not addressed in those sites because there was no space or time to heal. In Richmond, it seemed the grassroots activists and artists changed the monument into something that reflects on the past and imagines it anew. A platform for truth, reckoning, and actual care.”

Joel Garcia has been deeply involved with indigenous issues and the removal of the Christopher Columbus statue in Los Angeles. This past April he was also part of the actions resulting in the toppling of the Father Junipero Serra statue. Joel is an artist, activist, and cultural worker whose practice intersects with the national movement to remove monuments that reflect the racist history of the United States. He is the former Co-Director of Self Help Graphics and has worked in and around Los Angeles for a long time. In 2019 he was a Fellow in Monument Lab’s Shaping the Past project.

Joel Garcia, United for Stolen Lives, 2020

On October 22, United for Stolen Lives, myself and youth from East LA helped convert the steps of City Hall in Los Angeles into an altar commemorating the 650+ lives killed by the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriffs Department.

Recently, there has been some strong push back from the Catholic Archdiocese over the numerous Serra statues that have been pulled down throughout California. This contrasts to longstanding opposition of the presence of the Serra memorials and the Mission history narrative about Serra’s benevolence towards the native population. We spoke about this and other issues related to his activist practice, monuments, and his concerns.

Clayton Campbell: Let me start with your work around the Junipero Serra statue. Serra was canonized in 2015 by Pope Francis. It seems this is consistent with Catholic teaching despite long standing opposition by native people and now a broad array of the public. The Catholic Church has said of the toppling of the Serra statues “evil has made itself present here.” Yesterday, October 20th in San Francisco, Archbishop Cordileone performed an exorcism rite at the Mission San Rafael and called the statue’s destruction “an act of blasphemy.” He also did this in Golden Gate Park in June. Archbishop Cordileone decried the “mob rule” that led to the statue of the saint being “mindlessly defaced and toppled by a small, violent mob.” He must feel the same way about what happened here in Los Angeles.

Can you tell me what is going on in LA now that the statue is down? The Los Angeles Archdiocese is the biggest in the US. Where do they stand? Can the Catholic Church be a progressive force in retelling the history of California? Is the Church moving in the opposite direction of efforts such as San Francisco’s school district to rename schools inappropriately named after Serra?

Joel Garcia: Initially, the Archdiocese was pressuring the Mayor to reinstall the toppled statue, and then it was trying to get the city to gift it to them. Rather than seek dialogue they’ve dug in and remain committed to their own narrative. Even when the Columbus Statue was in process of being removed the LA County Department of Arts & Culture had offered the statue to the Archdiocese and they initially accepted the gift but had to back out because they had recently a new set of protocols with the First Nations of Los Angeles.

“Consultation to take place with local tribal or band leaders in order to assure accuracy in the presentation of cultural and historical displays relating to Native Americans at the missions, parishes and schools within the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.”

The Archdiocese of Los Angeles has proven over and over that it can’t be trusted and because they do have a small constituency of members that are Indigenous to California, they act as if that this is an out for them. That they don’t have to be accountable; but they do.

CC: What is next with this project? Is an empty pedestal more powerful after the act of removal? Is there a time limit to the cultural memory around this? Has something else taken its place to revalue this contested site with a different story, perhaps the one the community wants to tell? Will it last; does it need to be maintained to be “alive” and understood?

JG: Until the land is returned to the First Peoples of Los Angeles, it will be a contested site. At the moment there are efforts to ensure that there is an accurate and equitable representation at El Pueblo Monument aka Placita Olvera. For the moment, that empty pedestal does resonate in a bigger way than removing it outright. As with the Columbus Statue, it is important that the city removes that in partnership with the Indigenous community of Los Angeles and dedicate resources to authentically represent what has happened here in LA.

For the time being the community, those that were there during the toppling and others have started to use that park more consistently with relation to issues concerning Native/Indigenous folks. It is good to also see that the management team of El Pueblo Monument also desires an accurate narrative of LA’s history and more equitable resources to make that possible.

So by removing the statue, it has opened up space for more constructive dialogue with the city but it needs to be consistent and it can’t always be because the community needs to topple something in order to be heard.

CC: How do you change the narrative in K-12 education about something like the Mission history in CA? Can new monuments and memorials jumpstart this process?

JG: New monuments and memorials can definitely change the way K-12 education around the Mission System is currently offered to students. Cindi Alvitre, a Tongva member and professor at CSULB just released a children’s book about one of their creation stories. Her alongside some colleagues at CSULB were also selected to offer programming through a project I designed in partnership with the LA County Department of Arts & Culture, titled “Memory and Futurity in Yaangna” where they will offer a VR experience about Puvuungna, a site of origin for many California Indigenous Peoples. In addition to that program, Mercedes Dorame, a Tongva artist will install a temporary monument at Grand Park as well. Both of these efforts are ways in which we shift that current educational model. On Indigenous Peoples Day, Cindi led a reading of her book for families and this was sponsored by Los Angeles County Library. These programs came as a direct result of the Columbus Statue being removed.

https://heydaybooks.com/waaaka/

CC: I paraphrase, but you said in a conversation with Paul Holdengraber (Executive Director of Onassis Foundation, LA), that LA is a segregated city. It seems to me that LA is indeed comprised of so many different communities with so many untold stories, often quite separate, that I wonder how do you break down these barriers, how do we move forward together? Are monuments and memorials of unification and celebration possible right now? If not, what has to happen to make them possible? What might they look like if they are?

JG: The early ‘00s had such a unique overlap of communities that came together through the music and art scene and it was a direct result of the ‘92 Uprising here in LA and the ‘94 uprising by the Zapatistas, but that dissipated because of a lack of understanding of what is widely now known by many as intersectionality. That wasn’t a framework many understood back then. That is a concept that needs to be understood by the everyday person, by my mom, my uncle, etc. But outlets like social media have offered youth such a sophisticated understanding of race, gender, class, Indigeneity, etc. that new monuments and memorials, not crafted under a European influence, can bring communities together.

At the toppling of the Serra Statue, present were members of the Black, Armenian, Puerto Rican, Chicana/o, Phillipino communities among others alongside Native/Indigenous folks. This accurate representation of history isn’t simply important to us Native/Indigenous folks but to many other communities as well, because if as a city we are willing to be dishonest about our history, what else are we willing to be dishonest about?

Joel Garcia, Toppling A Statue At Olvera, 2020

June 20th (Summer Solstice) toppling of the Serra statue at Olvera. Seconds later, youth claim the statue and the pedestal, begin covering it with flowers, fruits, and other items and reclaim the space.

Joel Garcia, Toppling A Statue At Olvera 2, 2020

Joel Garcia, Empty Site and Pedestal, 2020

September 22 (Fall Equinox) members of the Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal where the Serra statue stood and converted into a site of ceremony and reclamation using prayer flags. These same collared ribbons were also used to obscure the plaques recounting the inaccurate history of Los Angeles.

Joel Garcia, Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal, 2020

September 22 (Fall Equinox) members of the Native/Indigenous community of Los Angeles repurposed the site and pedestal where the Serra statue stood and converted into a site of ceremony and reclamation using prayer flags.

CC: It seems that indigenous people, almost decimated in CA, have not had the power to keep their histories from being written by others. If money were no object, etc. what are the 2 or 3 stories (or just the one story) you would like to make as monuments in Los Angeles? And what shape might they take, what would their location be?

JG: As part of Shaping The Past a partnership between Monument Lab, the Goethe-Institut, and the Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (German Federal Agency for Civic Education/bpb), this is a conversation we had on Indigenous Peoples Day (to be broadcasted soon) with Cindi Alvitre and Guadalupe Rosales of Veteranas & Rucas, and I feel I am not the best person to offer such suggestions as California is not my ancestral homeland, but I can share what Cindi offered up, and she and others would like to see their ways of memorializing their ancestors with “Ancestor Poles” be visible within the city. Maybe a field with a hundred ancestor poles. In order to reconcile with our past here, we have to make space to honor what we destroyed in order to have this city. Some possible sites could be Olvera, the California State Park along Alameda, Grand Park, for example.

https://www.instagram.com/veteranas_and_rucas/

CC: Monument Lab is planning future work on the West Coast with its audit of monuments, maybe setting up field offices on the West Coast, and an exhibition of the Shaping the Past project you are a 2019 Fellow in. Can you give me a preview of this exhibition for Artillery’s readers?

JG: Part of this work has begun already as on the Fall Equinox we took over the site where the Serra Statue was and converted it. We changed the aesthetic of the place by simply using ribbons as you saw during the interview with Paul for Counter Memories. Because of COVID safety guidelines, we’ll be doing most of this work outdoors changing the way some of these places feel and look like to infuse them with ways of memorialization by Indigenous folks. For example, on November 2nd in East Los Angeles, we will be installing altars at 15+ sites where our community members were killed by the Sheriffs, and that’s just in the last 4 years, just in the East LA area.

But this work will also come in the form of the DIY culture prevalent in the Punk scene I grew up with, with some zines on how to do this work alongside the community.

CC: What work are you doing now and in the next year or two around the themes of monuments in the context of your overall practice as an activist and artist?

JG: Much of the work that exists at the moment around monuments is not sexy at all, it is mostly about shifting existing policies and funding streams to create truly equitable opportunities for marginalized and targeted communities to be represented, specifically the First Peoples of this city. I approach this work as an artist, as a hacker, finding loopholes to do things now and identifying current restrictions that need to change to be better reflect where we are now as a society.

And as an activist, I have to also keep a pulse on what the moment is feeling like. The Serra Statue was something many folks for decades attempted to remove but it was also recognizing the “Go” moment at the time to just get it done. But not recklessly either as it was meticulously planned, recognizing the legalistic realities of a toppling, and ensuring people’s safety as we had families present.

As an artist, you create big moments to uplift underrepresented voices and similar to the 2018 Banner Drop at the World Series in support of the Trans Community, we would probably be doing something just as big again during this World Series, so keep an eye out.

https://www.teenvogue.com/story/world-series-trans-pride-banner-drop-translatina-coalition

At this writing, we are in the aftermath of a contested Presidential election. The challenges ahead do not suggest collective acceptance of cultural narratives that can be easily agreed upon. How artists and creators like Joel Garcia, Ken Lum, and Paul Farber (along with their socially engaged colleagues who collaborate with new organizations like Monument Lab) go forward from here may tell us a lot in the next few years about our social and political destiny. It seems the necessity to speak truth to power by our artists and creative organizations is more important than ever before. Can artists contribute to activating a transcendent, collective healing and reconciliation? Will their memorials and monuments, whatever shape they take, be reminders of when we as a country authentically embraced a willingness to listen to each other without judgment? Is that our mandate, what must be accomplished, if our new and yet unrealized monuments are to endow future generations with wisdom, celebration, and truth?

Joel Garcia, Translatinal Coalition Banner Drop, 2018

On October 28, 2018, the Joel and the TransLatin@ Coalition, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that advocates for the specific needs of the TransLatin@ community in the U.S., unfurled a large banner reading “Trans People Deserve to Live” over the upper deck of left field during the game’s fifth inning.