Casey Kauffmann is a hoarder of cyber content. Her image archive is a black hole of digital debris, infinitely consuming, tearing apart, and spitting out images—a spaghettification of visual culture. Kauffmann is known for her digital collages that populate her Instagram page, @uncannysfvalley. These assemblages are strange, fragmented manipulations of a visual language that Kauffmann continuously rearranges and reimagines. A manic hyper-femininity runs through her work, combining asses, baby animals, and the latest photoshop filter to disorient and warp popular significations of women. Her digital practice also informs her drawing practice, which serves as another filter to contort and subvert constructs of femininity. I had a conversation with Kauffmann about coming of age in San Fernando Valley, the construction of identity on and offline, and the current state of digital art.

LAUREN GUILFORD: How did growing up in Los Angeles in the ’90s shape your practice?

CASEY KAUFFMANN: My dad worked for Mattel for 30 years making Barbie commercials, and my mom is a former pageant queen from the valley—I have a picture of her in the Hollywood parade wearing a fur bikini. I also have three sisters, so I grew up with a really strong femme influence. Anyone who grows up in LA—especially women and femme-identifying people—can attest to the oppressive nature of physicality, consuming images and ideas about what femininity is and should look like. Growing up, I was a huge fan of Lisa Frank, which has obviously influenced my aesthetic. All of this set me up to have a relationship to visual culture that is both celebratory and critical.

How do you view the role of the internet and technology as it relates to the construction of identity, online and offline?

I think the starting point for me is my personal history and the influence of social media and reality television. [It was] an era that didn’t just want to be in people’s living rooms; it wanted to be in their bedrooms. This idea of intimacy is a construct that is synthesized by the user. We seek out authenticity—or some idea of authenticity—and try to make that online. Can you be real in front of a camera or in the presence of being viewed? Can you access some sort of realness when you’re performing and being watched? In daily interactions, every interaction is a performance. I don’t think there is a fixed self when it comes to the formation of identity in person-to-person relationships. When the internet was developed in the ’90s, there was this utopic idea that it would be post-racial, post-gender, post–all binary constructions of identity. But there is no escaping these binary constructions when all of the options given to you are facilitated and made by a corporate structure. There’s a back and forth between us creating ourselves on the internet and the internet creating us AFK (away from keyboard).

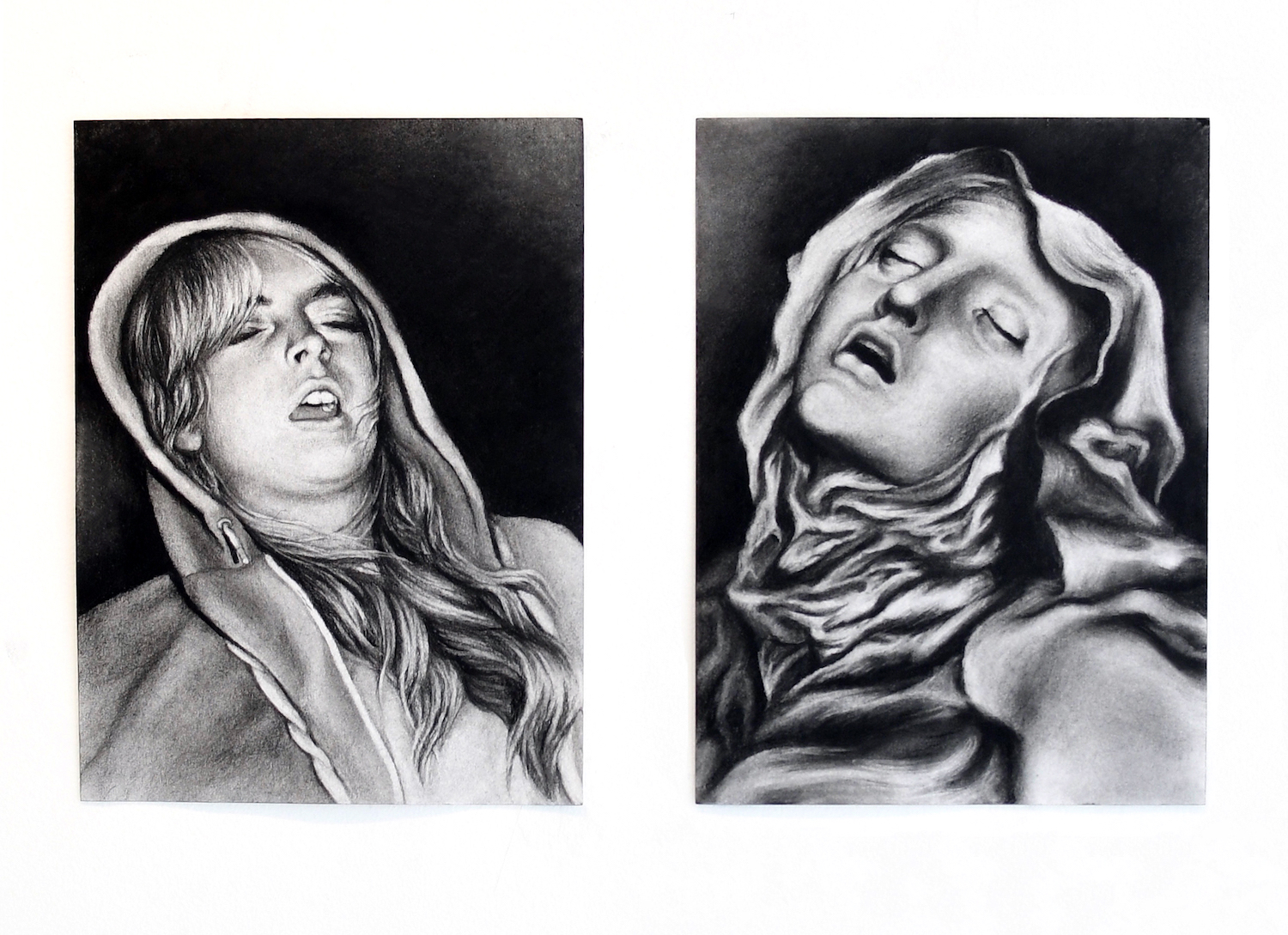

St LILO and St Teresa, 2017, charcoal on paper

Can you talk about your series, “Who is She?”

“Who is She?” started as a theory I developed for my thesis show when I was making drawings of women from reality television, popular culture and art history. I’m always interested in that crescendo of drama—the height of hysteric identifying femme emotion, and when I say that, I mean mass culture’s idea of what hysteria looks like. When I started making these drawings, I realized I could isolate that crescendo of drama and how it comes down to facial gesture—the gesture of a hand or lips, that undiluted high drama. I would crop out that part of an expression, then use the liquify filter on Photoshop, which is used to make eyes bigger, boobs bigger, waist smaller, butts bigger. I would manipulate the face to have the highest amount of drama in that digital image, then draw it, scan the drawing, then liquefy it again. It’s a kind of back-and-forth between the physical and the digital. I was also thinking about how I could bring my digital practice into my drawing practice and manipulate the image to get it to an abstracted, almost monstrous level. The title refers to the fact that these are disembodied gestures decontextualized from their source, which is often how we experience femme images online and shapes this visual lexicon of what a woman is.

There is a kind of sinister and playful tension in your work. Can you talk about the role humor plays in your art?

I consider humor to be an entryway. I’m talking about really difficult personal emotions, and when things are funny, they can access a wider group of people. The humor in my work comes from a real place of anger, anger about feeling like you’re not being listened to or understood. These things that are funny are also inherently tragic. I feel super-aligned with recent trends like Yassification and bimbo culture. Growing up watching the reality television show Simple Life and shows like that really influenced my concept of femininity. But what I love about Paris and what I love about a lot of these very front-facing iconic women is that they have to operate in this place of self-awareness. This is a kind of macro version of what women experience on a micro level all the time. All of this really defines my sense of humor. I would rather laugh than cry.

Do you keep a digital archive of the images you collect online? Do images reoccur in your work?

It’s a fucking mess. It’s my goal not to repeat images, but it has happened from time to time and, when it does, it’s super interesting. I’m not concerned about what an image means; I’m more interested in the dynamics of popular exchange that brings the image to my phone. It’s crazy when I look at collages from 2015 and see an image I used a week ago. Like, how did this cycle back through Tumblr or Instagram and arrive on my phone again? Is there any way to understand the ebb and flow of exchange? When I think about this exchange, I think about Hito Steyerl’s essay “In Defense of the Poor Image,” which has been an important text for me.

#2022sofar, 2022, iphone collage

You engage somewhat disparate audiences: the art world and the many sub-worlds that populate the internet. Navigating between these worlds must be challenging, but by doing so, I think you create possibilities for new art audiences. How do you keep these audiences in mind?

It’s challenging. I would say that when I make work, I think about audience in terms of accessibility and reaching a wide variety of people. Nothing gives me more joy than a 16-year-old commenting, “This is my life!” I identify with that sophomoric soul that’s inside of all of us saying, “Not fair!” I’ve become interested in the particular things that I can consume so I don’t think as much about what other people want from me. When it comes to traversing the art world, it’s tough—because I believe that conceptually the art world really understands and appreciates my work. Galleries claim to be interested in digital art, but they are still in the object-centric mindset and don’t really know what to do with my work—which has always been a struggle for digital artists. It’s sad that digital artists kind of get left behind in lieu of people making work that is more easily monetized. I also think my work would be more palatable if it wasn’t a bunch of pornographic images of women with their pussies in mud.

You’ve mentioned your intention to create a more “democratic” art world through your digital practice. How does your work expose the limitations of the commercial art world in terms of production and circulation?

My work is democratic in that it’s funny and made of things that everyone has access to. It unintentionally exposes limitations on production and circulation—conceptually and technically—but with the intention of accessibility. You don’t have to go to a gallery or a museum to view my work, which also creates a problem because the art world functions off of scarcity. So does the NFT space despite its inception of democratization and agency for the user. My work is not scarce. I have thousands of pieces, and anyone can view them. [It] is cheap in that sense, and I love cheap things!

Cassandra (drawn 4), 2019, oil pastel on paper

Can you talk about your recent NFT endeavor? How do NFTs relate to your democratic hopes for art?

I still feel hopeful about the NFT space. I know a lot of artists making conceptually rigorous work that is being sold successfully as NFTs. It’s exciting to finally have a means and an infrastructure for compensation for work in its native form. Showing my work in a VR environment is fucking awesome. It’s kind of the way my work is meant to be seen. In NFT spaces, the work goes beyond my Instagram page and operates in an archival way for these images that will eventually be lost forever due to tech changes and software updates. [It] is archiving the moments that these images are popular. I also think many people who run the NFT space are involved in too many projects to actually give the things they are involved in the proper amount of care and attention they deserve.

How do internet-oriented practices such as yours comprehend the world and the historical moment we are in?

This is a difficult time for digital practices. The internet is experiencing a kind of constant narrowing, starting as this big utopian and democratic idea and, as corporate ownership continues its stranglehold, things continually narrow. Since the pandemic, I can already see the homogenization of content through ideas of popularity and likes. I believe we’re on the precipice of a change where things are coming more from co-creative spaces like the blockchain and the metaverse where people are more interested in creating spaces together rather than interacting with things that have already been created for them, like Instagram, where you’re subject to what these white men in Silicon Valley have made for you.