In many Japanese artistic traditions, from sword making to ceramics, creative techniques have been passed down from generation to generation. Some artists today can boast that they are the 15th generation of an artist family, tracing their roots to the 17th century. In most cases, the artists charged with passing on family traditions are male since Japanese women were traditionally unable to pursue artistic careers. However, Japanese printmaker, installation artist and designer Ayomi Yoshida occupies the rare position of third-generation female artist in a family that has been celebrated for its contribution to modern printmaking in Japan.

Although it was her grandfather, Hiroshi Yoshida (1876–1950), her uncle Toshi (1911–1995) and to a certain degree her father Hodaka (1926–1995) who received the greatest renown as “Shin-Hanga” (or “New Woodblock Print”) woodblock-print artists of the early to mid-20th century, her grandmother Fujio (1887–1987) and her mother Chizuko (b.1924) were equally accomplished painters and printmakers and also showed their works in major exhibitions. Now, although her brother is a jewelry designer, it is Ayomi Yoshida alone who is carrying on the family tradition of not just woodblock printing but also pushing the limits of this ancient Asian medium, technically, geographically and now spatially.

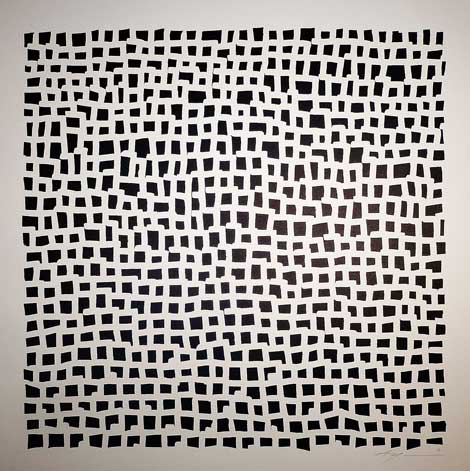

As a student, Yoshida did not intend to pursue the family occupation, choosing instead to study architecture at Wako Univeristy in Tokyo. However, while she was writing her graduation thesis, she conducted some research about architecture in California, where she began exploring silkscreen printing. After graduating , she wanted to continue but, was unable to find the materials she needed for silkscreening, she turned to woodblock printing techniques. Although her family did not directly teach her these techniques, her exposure to them at home coupled with her own artistic ability enabled her to carve her own designs out of woodblocks and evolve a new approach to the art. In many of her earlier prints, Yoshida cut into the wood with her chisel, scooping out oval forms, which she repeated across the surface to create prints characterized by rhythmic, repeating patterns, often in two contrasting colors.

In the 1990s Yoshida’s prints grew in scale, evolving into installations occupying large art galleries, the first of which was Clay Gallery in Tokyo in 1996. For these works, she carved similar ovals into painted plywood. The effect was of white roundels on a colored ground. She began saving all the carved-out chips and incorporated them into the installation, pasting them onto white walls to create a reverse red-on-white polka dot effect. In 2003, after seeing the exhibition “Japanese Legacy: Four Generations of the Yoshida Family” at Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the CEO of Target Corporation commissioned Yoshida to create a permanent installation at their Minneapolis headquarters, one that shouts fresh and modern. The company also hired her in 2006 and 2008 to design a line of wrapping paper and gift bags with the moniker “Ayomi Yoshida ART + DESIGN.”

Although Yoshida lives and works in Tokyo, much of her installation work has been in the America’s Midwest. Over the years, Yoshida has maintained a strong connection with Minnesota, revisiting Augsburg College to lecture and in 2010 creating the installation Reverberation for the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. For Reverberation and an earlier installation, Yedoensis, for Northern Illinois University’s Art Museum in 2008, Yoshida painted the silhouettes of cherry trees on gallery walls. She then printed tens of thousands of cherry blossom images onto one-inch-square sheets of thin paper, and she and a team of volunteers stuck them one by one onto the gallery walls, building up a snowstorm of cherry blossoms, like those that fill Japan’s springtime skies. The cherry blossom is a symbol of ephemerality in Japan. In Edo-period Japan (1600–1868), when woodblock printed ukiyo-e (“pictures of the floating world”) were at the height of their popularity, the flower was closely associated with the floating world, or ukiyo, namely brothels, teahouses and kabuki theaters, where people enjoyed fleeting pleasures before returning to reality.

Like the cherry blossom, traditions can fade and disappear as cultures change. Although Yoshida feels a great pressure to carry on her family’s art, she admits, “my rebellious nature helped me to develop different forms of expression than my forebears.” Ayomi Yoshida’s bold contemporary take on traditional Japanese art forms, techniques and motifs demonstrates a keen sense of her cultural and artistic heritage and the knowledge that traditions also need to evolve in order to survive for the next generation.

Yoshida will be lecturing at Cal State Long Beach on March 19th and at the Art Institute of Chicago on April 10th. Yoshida’s work can be seen at ayomi-yoshida.com