The photographs by Miles Coolidge recently on display at ACME, Los Angeles, are magnificently beautiful examples of the photographer’s craft. Simply as aesthetic objects, the photos are compelling: composed according to simple underlying geometries, they nonetheless display an inexhaustible wealth of infinitesimal detail.

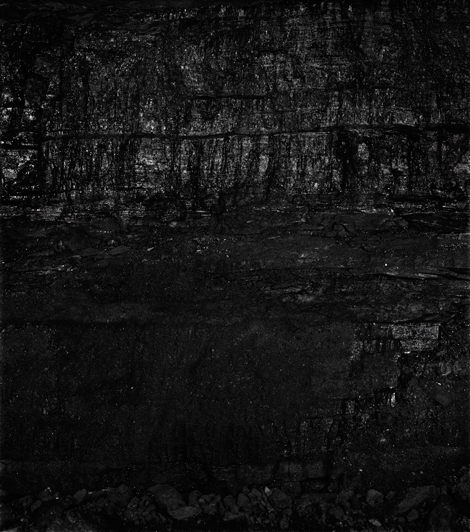

Aside from two recent examples of the ongoing series of UC construction mock-ups, the work in the current show includes a single monumental mural and four sizable black-and-white prints that make up a sequence: Coal Seam, Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel. Shot with an 8 x 10 view camera in a single day-long session, the four prints comprise studies of an “active working face” (the actual exposure of the coal seam) in a Ruhr Valley mine. Approaching the work is curiously like a descent into the mineshaft. The images at first are inscrutable abstractions. Then, suddenly, a narrow foreground space appears, strewn with rubble that abuts the vertical face of the seam, where work lights play over an extraordinary geography, every little rise and fall, crack and fault picked out to evoke a ghostly otherworldly terrain. About 75% of the way up from the bottom, each print shows a deep crack in the face of the seam, a pitch black horizontal mark that ties all the images together, and cuts each image with a crooked axis that suggests the lateral extension of the mine’s geography into a potentially limitless darkness.

Miles Coolidge, Coal Seam, Bergwerk Prosper-Haniel 3, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and ACME., Los Angeles.

Formally and geologically rich, Miles Coolidge’s Bergwerk Prosper-Hamiel series is deeply embedded in the complex history of mining technology, German industrialization, and more general history of attempts to understand, control and exploit the environment. It also resonates with the history of photography at its very point of origin: the oldest surviving “photograph,” produced by Joseph Niépce in 1826/27, employed a bitumen-coated plate—while, thanks to the brilliance of German analytical chemistry, the off-the-shelf Epson inks used to print the current series employ pigments likewise derived from coal.

Although comprising only a single colossal 92 x 221 inch image, Francis Gate (2010-2013) is another examination of man’s impact on the environment over time. We see spread out as though along the course of a slow cinematic pan, a one-year buildup of debris at the Francis Gate sluice, constructed in 1850 to facilitate control of the Merrimack River and the development of the textile industry in Lowell, Massachusetts. As the eye moves diagonally across the gigantic print, an uninflected jet black ground is increasingly displaced by a chaotic welter of form and color—primarily green and grayish-brown from a distance; the closer one gets, the more complex becomes the play of color accents, as the captured objects (natural and human detritus) are seen in ever-increasing, perhaps incrementally infinite detail.

In all, this is an extraordinary show, where images of profound beauty are used to ground an artist’s photographic practice in a rich if unexpected matrix. Theory, chemistry, industrial, artistic and social history all come together to illuminate the marks that we make both on and under the land.