Ari Salka is a trans, non-binary artist based in LA. Their ecstatic paintings and drawings—primarily self-portraits of their body—move in a liminal fantasy space brimming with queer angels and ghosts; a buoyant space where their present and former selves, can meet: recognizing, adoring, embracing and saying farewell.

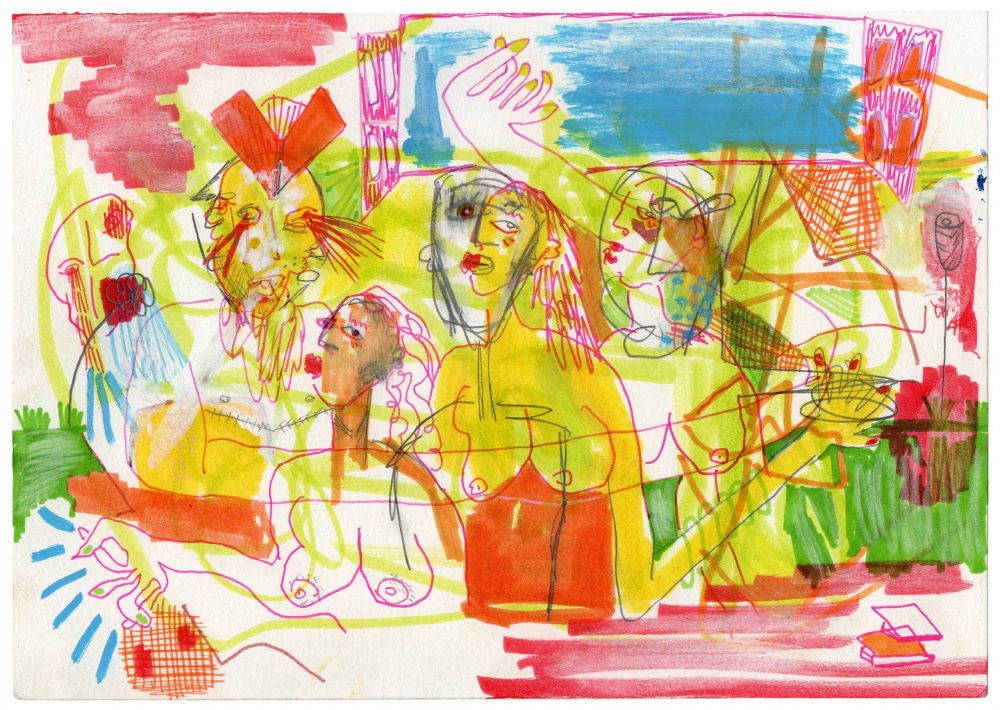

Ari Salka, Platonic Holding; Of You, Before and After Passing, 2019

Embracing the ever-changing self, embracing with equal measure the limitations, pain and delight of having a physical body is not work for the fainthearted. Salka does this boldly, unlocking all the doors to let in iterations of themselves to dance together with the hungry ghosts of loved ones whom they have merged with and departed from. There is the feeling throughout of humming a symphony in an effort to recall, rather than commemorate; of the mad project of transcribing the song of living that no musical notation can contain without combustion. To view their work alongside the poetic titles invites us to honor the very specific experience of the artist navigating their transitioning body, while enmeshing with symbolic dynamics that are universal: the failed project of unions, the terror of metamorphosis, the thin veil between embracing and strangling, and most importantly—that any cry of celebration carries also the low notes of the lamentations that bore us.

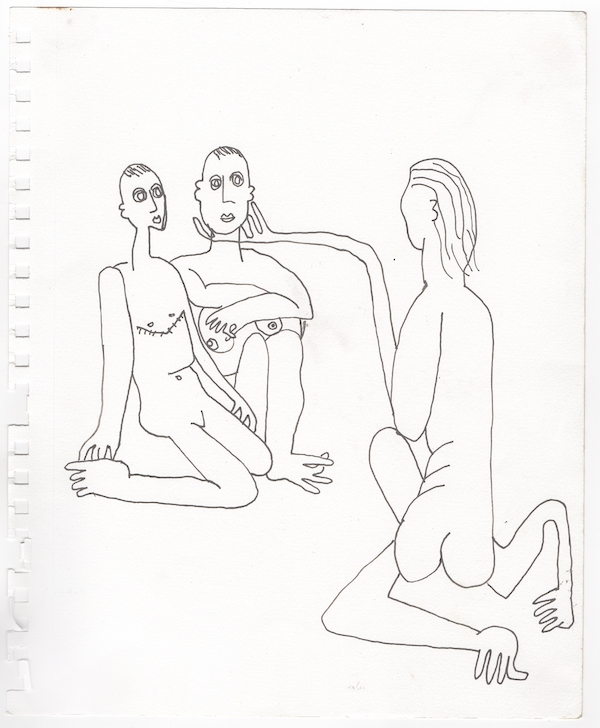

Ari Salka, Versions: Will You Still Hold Me? Would You Still Hold Both Of Us?, 2017

Salka achieves this most exquisitely with the way hands are rendered. These hands, often with extra, swollen fingers, extend from taffy-stretched limbs—limbs that wrap around and contort to reach and uphold themselves or another. At times, the limbs are flaccid, superfluous, and sit like resting snakes, as if they had burst out from the body for a momentary need to reach, and have now, in a new context, lost their mobility and function, with nothing left to hold onto. The result is superfluous appendages, which could just as easily get tangled up or be shed like lizard skin to float up like phantasms.

Ari Salka, When The Mask Comes Off At Bedtime And You Feel Purple, 2018

Salka and I spoke at length about the history of queer art, and what coded art means—not historically, but today, to us. We agreed admission to such work meant a ticket of shared suffering, the kind that comes with “knowing the other meaning;” but also a willingness to look, the tenderness to unpack the terms we thought we knew. I asked Salka about the multiples of twins in their work, expressing that their repetition, along with angel wings, breasts, scars and pills created an expectation—and much like the Medievalists’ depiction of saintly bodies—a chance for revelation. “Most of all,” Salka expressed, “developing my own iconography has allowed me to be the gatekeeper of my own meaning, my own body, myself.”

Bodies have always been political. In a moment when trans rights are under siege, Salka’s paintings resist; not only by showing us non-binary bodies, but hands prepared to reach out and lead us beyond the present political limitations, into a realm where these bodies are not withheld from view, not merely visible, but beheld and, most importantly, in their dynamic, breathing, singing, multitudinous forms—held.