In 1968, Beatle Paul McCartney approached Richard Hamilton, inventor of Pop Art, to design the cover for the follow-up LP to the game-changing Sgt. Pepper album of the previous year. Hamilton came up with a typically droll and elegant solution by taking the opposite extreme to Pepper’s psychedelic horror vacui—a completely white album cover with “The Beatles” embossed at an angle on the front and individually numbered in the lower right corner (making it a limited edition of 3 million or so), improbably linking the Fab Four to then cutting-edge visual art strategies of Minimalism and Conceptualism.

Fast forward 45 years: California-raised artist Rutherford Chang fills a SoHo gallery with the 600+ copies of the original vinyl pressing of The White Album he has accumulated over the last few years, mostly from trolling the Internet. That show—“We Buy White Albums” —presented the collection in a stripped-down version of a retail record store, with bins full of the same LP organized by serial number, a wall of display copies and two listening stations where audience members were invited to audit 4 ½ decades-worth of wear and tear on one of our culture’s most familiar and beloved sound artifacts.

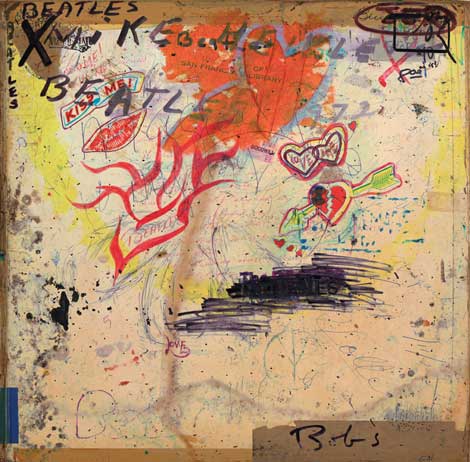

The real aesthetic payoff was the album jackets, with Hamilton’s minimalist void altered idiosyncratically with tags of ownership, repositioned track listings and more than occasional attempts to provide the psychedelic cover art that never was. On top of this layer of horror vacui graffiti is the abrasion and grime from years of handling, and the frequent random disintegration of the white cover slicks to reveal the brown cardboard beneath.

The result is a strangely moving inversion of Walter Benjamin’s description of the elimination of an artwork’s unique aura through mass media reproduction—what began, at least in part, as a knowing wink at the vacuous genericism of the globally marketed commodity The Beatles had become, became the tabula rasa for thousands of uniquely individuated artifacts. Presented in a pre-loaded “white cube” gallery space and not available for purchase, Chang’s collection of White Albums were allowed to reveal their truly iconic function.

The second phase of Chang’s project was to compile the accumulated differences into a singularity—a limited edition mixdown of multiple versions of the time-worn vinyl into a dense, off-register thicket of sound. This artifact has just been released via Chang’s tumblr page (though the link to purchase the LP mysteriously vanished after a few days—intellectual property goons?).

The packaging is a gorgeous analogy of this layering—a Reader’s Digest condensation of the most interesting modifications—front and back, gatefold, even the Apple Records logo labels—into a dizzy palimpsest of lyric fragments, mildew stains, library stamps and Dayglo cartoons. Replacing Hamilton’s original photo-collage poster from the original set is a 24 X 24-inch poster displaying a grid of the covers from Chang’s collection.

The sound is amazing. I’m a little skeptical about the claim that the record actually consists of 100 different versions superimposed, and there’s almost certainly been some mixing involved, as one or two tracks seem to be foregrounded over the massed chorus in back. This makes the songs easier to identify and follow—at least at first.

As each side plays, the different layers gradually shift out of sync, creating a cloud of ghostly reflections that precede and follow the lead line. What at first sounds like a party in the next apartment where they’re playing The White Album gradually transforms into a lost tape loop piece by Terry Riley or Steve Reich —full circle back to Minimalism!

While the formal components of Chang’s project aren’t strikingly original—piss-takes on Minimalism’s supposed purity are almost as old as the movement itself, and artists like Christian Marclay, John Oswald, Sean Duffy, Tom Recchion, Philip Jeck and many others have issued conceptually-motivated remixes of pop records—it is his choice of source material that makes the appropriation remarkable—creating not only a compelling exhibition, object and recording, but initiating a Duchampian depth-charge that resonates across time and simultaneously into the worlds of mass consumer culture, contemporary art discourse and hauntological interiority.

Too many artists seem to think that Duchamp’s magic wand can be waved over any piece of crap and transform it into something significant; Rutherford Chang’s White Album variations demonstrate that some readymades are more ready than others.

All images courtesy of Rutherford Chang

RUTHERFORD CHANG, The White Album

For more info: http://rutherfordchang.com/white.html and http://100whitealbums.tumblr.com/