“Chris Burden: Extreme Measures,” at New York’s New Museum is the artist’s first major exhibition in the U.S. in over 25 years. A legendary provocateur, Burden has challenged traditional concepts of art through his galvanizing performance pieces and later thought-provoking sculptural work, consistently questioning physical, moral and structural limitations over the course of his 40-year career.

I first encountered Burden as a goggle-eyed schoolgirl, introduced by my much older cousin, an art historian, who showed me a catalog of his work. I remember poring over Shoot (1971) and Trans-Fixed (1974), trying to make sense of them. They profoundly disturbed me because they seemed to shake the very foundations of what I thought, not only about art, but about rationality itself. In the end, my “why?” questions unanswered, I gave up, dismissing Burden as a complete loon.

Of course, as my thoughts about contemporary art evolved over the years, I came to appreciate him and his enormous impact, and to accept that back then, putting himself at risk, using his body to test his and his audiences’ limits, was central to his artistic expression.

But I’m still not sure if having yourself shot in the arm (I discovered via a BBC interview playing on a continuous loop at the show that Burden actually had intended only to be grazed by the bullet) or nailed to a Volks-wagen, qualify as visual art. They’re certainly something, but to me it’s more akin to a theater-philosophy hybrid. Burden was not alone in this type of art-making. Plenty of post-Duchamp artists engaged in this, often shocking, dematerialization of art. For Burden, as for others, it served its purpose, recalibrating things in such a way that a return to the object once again became possible.

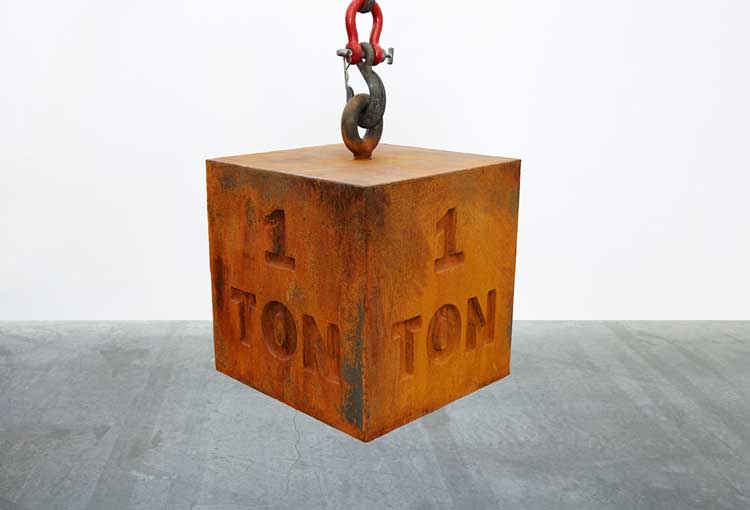

With his objects, one thing’s for sure: Burden is obsessed with weighty issues (pun intended). Big ideas and big work abound. Nearly all his pieces are immensely heavy, and those that aren’t: A Tale of Two Cities (1981), All the Submarines of the United States of America (1987) and L.A.P.D. Uniforms (1993) make up for it in their size. It’s as if when he made the switch from nonobjective (weightless) performance art to sculpture, he used bulk as a means to anchor himself.

Burden has quite literally taken over the New Museum, with work on the roof and every floor below. He’s even on the front of the building where his 2-ton 30-foot wooden Ghost Ship is mounted. It’s a strange apparition against the sleek Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa/SANAA façade. In 2005 the unmanned vessel made a 400-mile journey between Fair Isle, Scotland and Newcastle upon Tyne, England, navigated by computers. It’s in far stranger “waters” here. A meditation on the nature of energy, Burden’s The Big Wheel (1979) features an enormous cast-iron flywheel with a 1968 Benelli 250cc motorcycle positioned in front. When the bike’s backed up so rubber wheel touches metal and the motor revved to 200 rpms, the flywheel is set spinning. This kinesis continues for 2.5 hours after the motorcycle is switched off. Cool, huh? It’s also really cool looking, a 19th-century/20th-century pastiche of esoteric bright blue motorcycle and simple, yet massive rusted flywheel.

Then there are the bridges. This is where Burden wins my heart. I love his obsession with these early structures of industrial design and the painstaking care with which he recreates them using metal toy construction parts—and in Three Arch Dry Stack Bridge, ¼ scale (2013), hand-cast concrete blocks. They are things of beauty and testaments to his devotion to his art. I think my favorite one is actually unbuilt. The ultimate Erector set, it’s the Tyne Bridge Kit (2004), which he came up with after he’d gone to such lengths to produce the original downscaled version of that bridge. Weighing in at a ton, the kit consists of the tools, blueprints and the 200,000 parts needed to erect the model, all of it housed in an elaborate wooden chest. Burden’s idea is not so much that you would build it, but that you can see the bridge in condensed form. I love the uselessness of it: the enormous effort put into something that has no practical purpose. All the parts are there, but the bridge exists only as an idea. To me, this piece tells you what you need to know about Burden: his integrity, vision and unflagging commitment to his art, all of which are so eloquently embodied here.

“Chris Burden: Extreme Measures” at The New Museum in New York, runs thru Jan. 12, 2014; info newmuseum.org