It’s an uncharacteristically cool, rainy afternoon when I climb the steps to Judie Bamber’s home and studio in a neighborhood off Sunset. As I enter her studio—a surprisingly spare and self-contained space—a rectangle of golden light seems to float on an easel set up at the rear of the room, seemingly appropriated from some magic hour we’re bound not to see on that particular day. As I move further into the room, I see that it’s a work in progress—with portions of the painting covered around this rectangle, which now discloses an identifiable section of human anatomy.

This is familiar terrain for Bamber—whose work almost always implicates the human body, however abstractly or indirectly—freshly defamiliarized. I’m drawn in, but my intrigue is checked, my reading at best provisional. The section floats, dislocated and slightly decontextualized. Bamber shows me the source for the image—a Playboy centerfold.

This is my first studio visit with the artist, although we’re familiar with each other from gallery openings and art events in Los Angeles. Bamber is relaxed and unassuming—her face framed beneath a soft, shaggy fringe of ash-blond hair, squarish eyeglasses, with a sensual smile that occasionally breaks into a toothy grin—with the casual poise of the teaching artist well-accustomed to introducing and talking about her own work with both collectors and students.

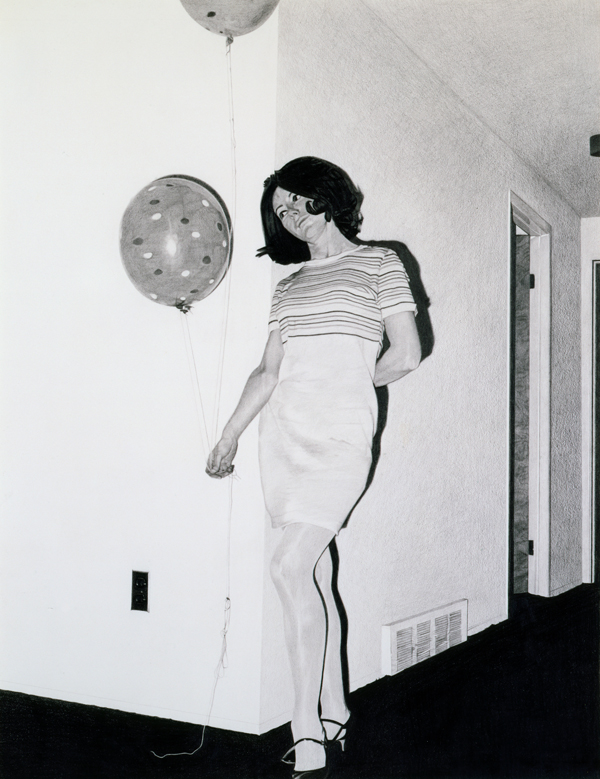

Mom on Red Carpet Study 1, 2008, Graphite on paper, 20 3/8 x 15 5/8 in.

We chat briefly about her appearance a month earlier in a group show at Wilding Cran, where she showed one of the works that are a kind of postscript to the watershed 2011 show of what she now calls her “Mom paintings” (and drawings) at the since-shuttered Angles Gallery, “Are You My Mother?”—a zeitgeist moment at the time, the culmination of a number of bodies of work that seemed to anticipate a full figurative flowering of the ideas and images that had preceded them, and arriving more than six months before Alison Bechdel’s identically titled graphic memoir. We also talk about a series of works that preceded this show which, with the “Mom” paintings, frame a kind of origin story—the series of watercolor paintings from 1995 to 2001, she called simply “Snapshots,” taken from photographs of her father, an amateur artist himself, who introduced Bamber to painting as a child, and who died in an automobile accident when she was just eight years old.

It would be a number of years before Bamber returned purposefully to this trove of photographic material. Her re-approach was less circuitous than a matter of periodic revisit and eventually, through a framework of ideas and strengthening self-awareness, she found what she had been looking for all along. And as we revisit this subject during that January afternoon, I realize this applies to the fragmented image she has just shown me. It’s clearly a fresh departure for her work, yet one which she sees “on the same continuum” with most of her previous work.

There is an aspect of possession or repossession to Bamber’s spatial approach, complicated by both artist’s and viewer’s relation to that space and the image or objects in it and their relation to each other; also the duration of their occupation and observation of those spaces. “Time is important in all of my work, whether it’s placing the image in time to evoke the personal and historical, or if it’s the time contained in the rendering of the image.”

Artist Nayland Blake, an early mentor, drew a contrast between the way “distances were mingled” in the compositional space of the sardonic object and still-life paintings she produced in the mid- to late-1980s, and the durational distance evoked by her melancholy, minimalist 2005 seascapes. Revisiting these very different series in 2018, we’re each struck by different qualities. Bamber makes a note about the “centrality” of her compositions, which triggers paired memories—first, that she may have inherited this compositional bias from her father; also the memory of being scolded by elementary school art instructors for “wasting paper” by centering her subject and leaving so much “empty space.” I am again struck by the contrast between the cool, variably dispassionate and clinical affect of the images, and the sarcasm of the titles; also the extent to which ideas animate her work. It’s difficult not to hear the echo of actual conversations in such titles, but they’re ambiguously placed—from childhood, from adulthood, conversations both intimate and entirely academic; and many of them involve attitudes and approaches toward the body.

Bamber was as influenced as any of her peers by CalArts’ rich history of intergenerational, broadly philosophical feminist dialogue. Given that backdrop, she was all the more perplexed at the simultaneous preoccupation with the body and quasi-puritanical horror at the notion of its pictorial representation as a subject of art that was prevalent around her. “I realized it was a generational thing. But wait a minute—this turns us on. Why can’t we do this? Aren’t we missing something by adhering to that?”

What Do You Say? (Chrome Egg Butt Plug with Leather Thong), 1989, oil on canvas stretched on board, 25×25 in.

What Do You Say? (Chrome Egg Butt Plug with Leather Thong), 1989, (detail) oil on canvas stretched on board, 25×25 in.

Bamber rebelled discreetly with images of objects and garments in some proximity to the body (e.g., “empty corsets”) without showing the body itself. The paintings that followed carried this dialogue forward into an introspective monologue that placed the formal evolution of her work on a parallel track to her personal evolution. One of the first of these announced (in typically subtle fashion) the direction she would be moving in: Because She is Always Anxiously Awaiting the Onset of Pain (Canned Pea and Bruise) (1986). From there, she moved beyond canned fruits and vegetables to, among others, a June bug, a dead baby finch, an oyster—with titles like, Excuse Me for Living (Spearmint Freshen-up Gum Whole and Squashed) (1988), I Told You So (Vitamin E Capsule, Whole, Squashed, Reinflated) (1988) and (for the finch), I’ll Give You Something to Cry About (Dead Baby Finch) (1990); then later to sex toys: a Ben-Wah ball is titled, Well it Didn’t Just Get Up and Walk Away (Ben-Wah Ball) (1989).

Given the fragility and limited shelf-life of some of her still-life subjects, photography had become an important tool for Bamber. It was also becoming a significant element in her ongoing consideration of the cultural biases implicit to the medium, its potential affect, the viewer’s gaze and its relation to spatial abstraction.

It occurs to me that some of the titles take on a slightly confrontational edge: Someone’s Going to Get Hurt Here and It’s Not Going to Be Me (Marshmallow) (1988). The spatial isolation and rigorous centrality of the composition reinforce this affect. It was around this time, Bamber found herself ready to move on from still life to portraiture—after a fashion.

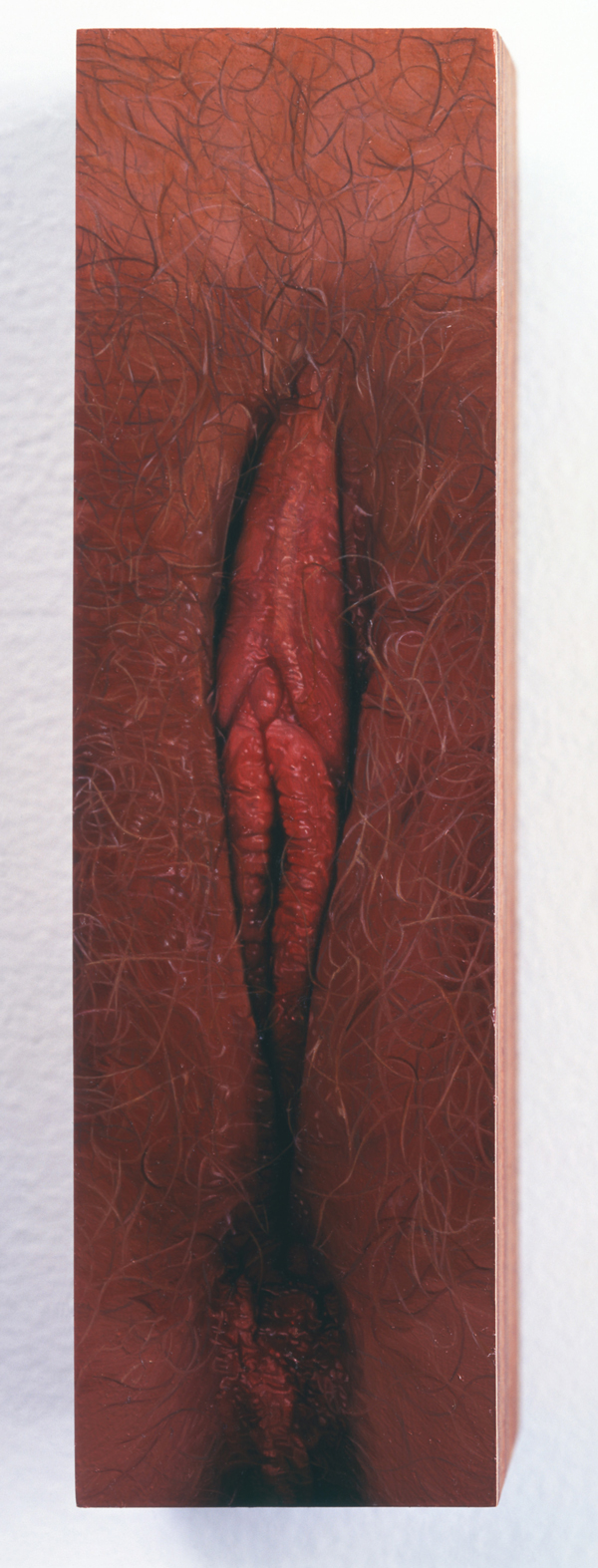

Untitled #2, 1994, oil on panel, 6.5×1.75 in.

“The vagina paintings were a start—doing everything wrong by using the female body and fragmenting it. I had this realization that I could be fairly confrontational. But the fear was about being a bad feminist.” She had experimented early in her career with breasts, somewhat on the order of her object paintings. But “these vaginas belonged to actual people.” The three vaginas were painted to be just slightly larger than life on wood panels—to be viewed just as they would be in life. The photographs she referred to presented further complications. “There are things in each of them you can’t really identify because the photograph abstracts them.”

“The hyper-realist vaginas are simply among the great feminist works,” comments art historian, writer and critic, Amelia Jones—“among the most trenchant, beautifully painted, and conceptually rigorous works being done [in the 1990s] period.

“[They] throw back at the viewer precisely what Western fetishism seeks to disavow and delay (the desired yet feared female sex) …challenging not just sexual fetishism, but commodity and photographic fetishism, as well as proving a locus for potentially queer feminist/female desires.”

Bamber was soon to be challenging that fetishism as daringly with lurid images of Lizzie Borden’s murdered parents, in a palette intended to resemble dried menstrual blood (which she originally tried to execute on panties).

Mom with Balloons, Mom with Balloons, 2005, Graphite on paper,18.87 x 14.5 in

It was at about this point, or at least by the late 1990s, that Bamber was again considering the photographs she had revisited periodically since childhood. Encountering Bamber’s work for the first time at the time I did, I had the sense that she was constructing a kind of first-person narrative in this work, but our subsequent conversations correct and complicate this view considerably. To begin with, family photographs, however casual, can never simply be tools. In the “Snapshots,” series, the coloristic quality of the photograph is itself considered—an almost meditative aspect that is not accidental. Nor was it mere coincidence that she had been reading Roland Barthes’ own meditation on photography, Camera Lucida. I had asked her about the dates and times in the titles of the individual paintings. “I think that mattered to me because I wanted to connect to Barthes’ ideas about the photograph always being a representation of death and the Walter Benjamin quote, ‘A man who died at the age of 30 would be forever after regarded as a man who, at whatever stage of his life, would die at 30.’” (Bamber’s father died at 31.) Bamber characterized the transformation from “snapshot” to finished painting as simultaneously “seance and exorcism.” As a narrative, “it would be the fantasy of finding something in the photograph that can no longer be found. I remember painting his hand and having a kind of sense memory.

“In both the ‘Mom’ and ‘Dad’ work, there’s a piece about giving him a life he didn’t have, placing him in a way he otherwise wouldn’t be known in the world.”

The evolving spatial and temporal dimensions of Bamber’s work come into sharper focus here. Risking the conceptual elegance of her earlier work, the formal complexity of Bamber’s work begins to be matched by a level of psychological complexity. That would include the deceptively “minimalist” seascapes she executed plein air in watercolor before transposing them into oil on canvas. It was not long after completing this series that Bamber found her way back to the figure in full—again by way of family photographs, but more specifically photographs of her mother that, by design, carried a certain charge. Most (though not all) of the photographs that led to Bamber’s “Mom paintings” were deliberately posed and taken by her father. Several were intentionally erotic, but more often they were posed with a view to her mother’s aspirations to become a model. (She would eventually become a hair model.) The photographs encompass an astonishing range of poses, attitudes, viewpoints and spatial perspectives, and moods—and the drawings and paintings Bamber made of them deepen that range still further.

There’s also a kind of parallel reenactment in Bamber’s transposition. She captures the tension between her mother’s engagement and deflection in the photographs. “She’s completely ignoring the person who’s capturing the image,” Bamber says. “She’s absorbed in what she’s doing.”

The quality of the moment, evoked not merely in the details, but the light and deepened contours, is almost palpable in some of these drawings. A few reach back to still older traditions of portraiture—ambiguously pitched between her father’s original styling and Bamber’s own rendering in graphite. But Bamber’s own claim on this moment, and her disruption of its ostensibly hetero-normative domain, is clear. At one point, Bamber interjects her own gloss of its “Freudian aspect” as something “like the primal scene and the desire to interrupt that and put yourself between the mother and the father—and having her to myself.”

Melodye Prentiss (MISS JULY 1968), 2018, watercolor on paper, 20.75×14.56 in.

Two months later, on a chilly March evening, I am again in Bamber’s Silver Lake studio, gazing at the same painting (now titled) that greeted me on my first visit. Its seductions are magnified in proportion to its finished dimensions. So is its abstraction. Of interest to both of us is the extent to which the focal point shifts away from the figure and into passages that are almost unidentifiable. Again we’re confronted with the pre-existing abstraction of the photograph’s limited depth and its further abstraction here into something lushly chromatic and sensual without reference to the torso in close proximity. Bamber has taken liberties with contours and color intensity, but that can’t entirely explain “where the focus falls.”

“For me what’s most important about the work is what the image refers to in the world, the way it’s chosen, and the way its rendering comes together. That’s always the place I’m trying to get something to happen.”

Our gaze at this point might simply evaporate from the luminescent upper quadrant of the painting. We’ve come full circle to that barely-there punctum—that evanescent bruise in the interrupted narrative of the “princess and the pea.” It’s breaking the spell of “origin” narratives and moving on to what for the moment we may have no words to identify.

Images courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles