Drawing makes you look at the world more closely. It helps you to see what you’re looking at more clearly. The image is passing through you in a physiological way, into your brain, into your memory—where it stays—it’s transmitted by your hands.

—Martin Gayford, A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney

Way back in the 1970s, as part of my graduate studies in Pre-Columbian Art History, I did two summers of archaeological fieldwork in the Valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. We walked over the mountainous terrain collecting potsherds and other evidence of ancient settlements. When the head archaeologists learned that I could draw, they hired me to do precise ink renderings of every artifact we gathered. The artifacts were recorded in photographs as well, but my stipple drawings—where the contours were articulated by tiny dots—described the three-dimensional shapes in a manner that photography could not do, because of its inherently flattening nature. It was an important lesson in how human vision differs from mechanical reproduction, in how drawing describes the world in ways photographs cannot.

Andrea Bersaglieri, Suburban Tuft, 2017, oil on canvas, 16×28”

In this essay I explore examples of realistic drawings that are based on direct observation and executed with technical precision. Many such drawings straddle the art/science divide, presenting the world for aesthetic contemplation as well as veristic record-making and analysis. Pointing out that drawing is “physiological,” that it is “transmitted” from the artist’s mind to our field of vision through physical acts of the artist’s hands, British writer Martin Gayford highlights how drawn responses to objects from the external environment move into internal awareness, into the “brain” and “memory.” Realistic drawings are generated by targeted looking, by focused visual attention being translated through the body into the controlled marks of the drawing tool. In addition to their (objective) impact, the physicality of realistic drawings can evoke the (spiritual) connection between human viewers and the materiality of the natural world.

Albrecht Dürer

Renaissance master Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) created his astonishing colored drawing known as the Great Piece of Turf in 1503. The drawing is so faithfully rendered that we can identify each of the nine plants depicted: cock’s-foot, creeping bent, daisy, dandelion, germander speedwell, greater plantain, hound’s-tongue, smooth meadow-grass, and yarrow, all of them wild plants or weeds native to Dürer’s Germany. A century later, another German artist—Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717)—would take realistic drawing to a new level in her scientific illustrations of flora and fauna from Europe and the New World. (In the early 19th century, when British scientist Anna Atkins [1799–1871] wanted to produce even more precise botanical images, she abandoned line drawings in favor of photograms. Atkins’ book about seaweed was the first volume published with photographic illustrations.)

Scholars have connected Dürer’s super-real turf drawing to the writings of medieval friar Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280) who, like the later German artist, based his work on the direct observation of nature. Conceptual antecedents for the empiricism of both Magnus and Dürer are found as far back as Aristotle’s natural philosophy. I rehearse this intellectual genealogy to emphasize the depth of Western Culture’s impulse to study and reproduce nature in a realistic or “scientific” fashion. Before photography, the best tool for such study was drawing. It remains an effective tool for numerous LA artists today.

Sometimes, drawing can achieve a realism that is more precise and detailed than possible in human vision: In addition to the microscopic precision of the carefully rendered leaves and seeds, Dürer limned plant roots that normally would be hidden underground.

Andrea Bersaglieri, Dirt, 2017

The German artist’s fastidious approach is echoed in the contemporary work of Andrea Bersaglieri who has spent the last two years drawing fragile ribbons of Bermuda grass, each piece ripped from its dirt bed and curled onto a white background. Tentative slivers of green balance the brown roots and stalks in graceful, almost musical compositions. Isolating the tiny fragments of grass forces consideration of their individuality, instead of seeing them subsumed by the velvelty green blankets long considered de rigueur for residential front yards. Bersaglieri has also drawn cacti and succulents, often employing radical close-ups so that the plants are seen in new and increasingly intimate ways.

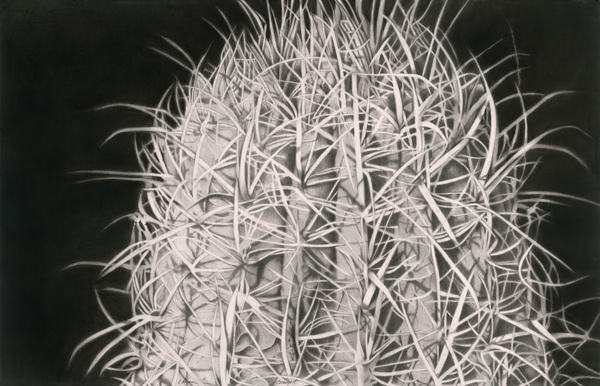

Catherine Ruane, Convert, 2015, 38×42

Catherine Ruane employs a similar process. Her “Desert Survival” series pulls us close to sharp, spiny surfaces, harsh pointed stems and translucent white blossoms. Ruane’s images are so convincing that many think her works must be black-and-white photographs, rather than charcoal on paper drawings. Her aesthetic quest is not simply documentary, however. The artist describes the connectivity of her studio practice: “Making art is a process of study and note-taking. Drawing is akin to some form of worship. I see the studio process as a search into the mysterious border where the physical meets the mystical. I methodically build images as a visual expression of the contrasts between the appearance of natural, wild forms and what they have come to symbolize.”

Catherine Ruane, Cloisture, 2015, 30×40

Ruane’s statement recalls the meditative practice of focused awareness. As spiritual master Davidji reminds us, “Every moment in our existence begins with awareness. If we are not aware of something, it doesn’t exist in our consciousness. But when we place our attention on that thing …poof! It becomes ‘real.’” In order to draw realistically, artists must practice focused awareness. It’s a bit like meditating. And because all of us have done pencil drawings—whether we went on to become artists or not—we can remember the process of directed awareness and the physical act of translating the world into lines. We can remember how, even as children, we focused on and thereby connected with the subjects of our drawings. That body memory enhances our later response to drawings by others.

Catherine Ruane, Transgression, 2015, 30×40

Ruane’s metaphysical approach also recalls Aristotle’s assertion that “In all things of nature there is something of the marvelous.”

Terry Arena, ”Swarm” installation, 2017, Photo by Bryan Birdman Mier

Terry Arena, Symbiotic Crisis Series (Studio image), photo credit Kristine Schomaker

Terry Arena points to the marvelous in her drawing of fruit, nuts, seeds, bees and fragments of honeycomb. Each object is drawn in miniature scale, sometimes so small that the artist has to hang a magnifying glass next to the artwork to allow viewers to see the details. There is a quiet longing in Arena’s patient depictions of endangered species (bees), overripe pomegranates, and the desiccated carcass of a tiny bird. Her nostalgic allusions to death and loss function as postmodern memento mori, reminding us that the material world is a fleeting phenomenon. That we, too, shall pass.

Joanne Julian, Ruby, 2014, Prismacolor on paper, 22 x 30 in.

Joanne Julian creates elegant portraits of the plants that populate her garden and the various Southern California eco-zones through which she travels. Tropical flowers—ferns, Birds of Paradise, calla lilies, Halconia, and orchids—especially thrive under her pencils. Although the plant “portraits” are rigorous and literal, they are so carefully composed and exquisitely executed that they transcend illustration. Often, Julian pairs her meticulous botanicals with spontaneous splatters of ink that recall both Japanese brush painting and Robert Motherwell’s Abstract Expressionist flourishes. The tight drawing contrasts with the painterly fluidity of hoboku (“flung ink”) to create a poetic visual tension empowering Julian’s oeuvre.

Joanne Julian, Red Bird, 2014, Graphite and Prismacolor on paper, 30×22″

I discuss Julian’s drawings as “portraits” of plants, but there are several truly gifted practitioners who draw super-real portraits of people. One LA artist who produces remarkably realistic portraits is muralist Kent Twitchell. Looming several stories over the streets they adorn, Twitchell’s immense paintings are always based on fastidiously rendered pencil drawings. A gigantic Ed Ruscha towers above the downtown LA Arts District, but the portrait originated as a small, graphite-on-paper drawing.

Twitchell’s drawn portraits recall those of French academician J.A.D. Ingres (1780–1867), such as his 1819 portrait of violinist Niccolo Paganini (1782–1840). In his brilliant book Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (2001), David Hockney suggests that Ingres used the camera lucida to enhance the realism of his images. Whether he did or not, Ingres achieved a remarkable realism—a realism paralleled by Twitchell.

Abel Alejandre, Mis Nopales (My Cactus), 2007, (detail) 40 x 32 in., graphite on paper

Abel Alejandre creates similarly realistic graphite portraits of friends and family members. In discussing the nature of drawing, David Hockney once said, “To reduce things to line I think is really one of the hardest things.” But Alejandre translates his world into black lines on white surfaces with such power and grace that it must not be quite so hard for him. Particularly poignant are the images of his father, whose wizened features speak of the hard life of an immigrant.

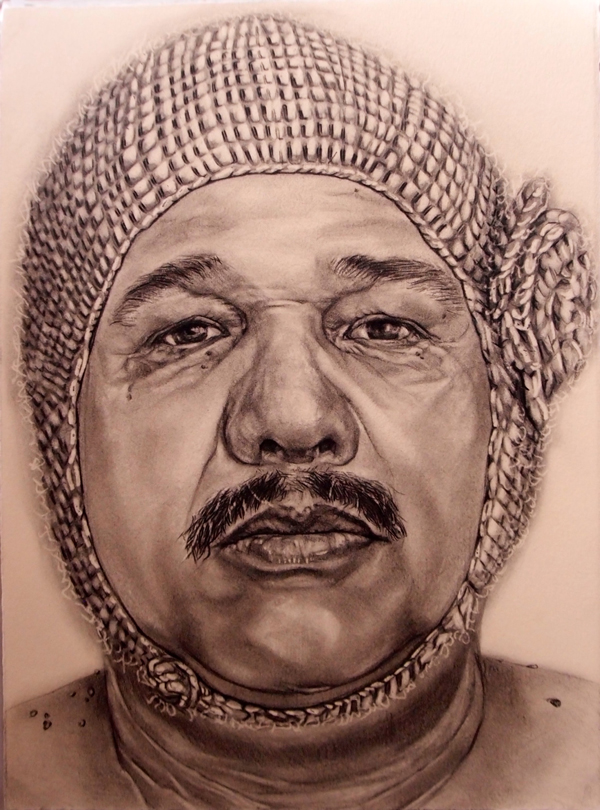

Gabriela Castillo, Edgrado,

Another artist who does intense portraits of family members is Gabriela “Gabby” Castillo. She has portrayed many relatives—young and old, male and female—wearing knit beanies topped by yarn pompoms. The chiseled faces of her male subjects contrast humorously with the soft, feminine headgear to make ironic statements about gender and identity.

J. Michael Walker’s remarkable portraits of Bahia women are done in colored pencil. His Portrait of Angelica is presented not on regular drawing paper but on 10 pages from a 1940 book on Brazilian history: The elderly woman’s powerfully present face hovers over the records of her roots—records produced and controlled (of course) by male writers.

J. Michael Walker, Lady at the Crossroads, 2015, color pencil and crayon, 36 x 36 in.

As New York artist Keith Haring reminds us, “Drawing is still basically the same it has been since prehistoric times. It brings together man and the world. It lives through magic.” As I created those stipple drawings in Mexico, I was engaging the same observational and record-making “magic” that Dürer employed—and after him, artists from Maria Sibylla Merian to J.A.D. Ingres to Don Bachardy to, well, all of the amazing artists discussed here.