A little more than 40 years ago, I was home from school and living in an apartment in Westwood. I didn’t see my brother – who was also in Los Angeles that summer, freshly graduated from Yale – very often; but when I did or when we spoke over the phone, we would frequently talk about books we were reading or that had just come out or were anticipated to be coming out, the most urgent, compulsory, compelling reads, the books we couldn’t put down; the books that should be on my must-read list (he was always a flying leap ahead of me, forever my tutor and imposing upon me the essential political, Russian, French, Brit, etc. reads). We were children of Hollywood and escapees from the San Fernando Valley in heavy denial about everything we had been through in those years before we trekked off to our respective colleges. The immediate cultural backdrop was the vague academic limbo that immediately precedes or follows college, movies, rock music and the business and hustle around it, and tennis – which I was not playing. Although I was personally obsessed with movies, my brother was not, and they had nothing to do with the kind of writing, whether literary, journalistic or polemical by which we were specifically engaged. That ‘reality’ – though, as the reader may easily infer, our grasp on it was somewhat tenuous, if not completely illusory – was really defined by New York literary culture – with which we were obsessed.

I didn’t need to be told to read Renata Adler’s Speedboat, but as usual, having read it first, my brother pressed it upon me. We were both familiar with Adler’s writing from The New Yorker and prior to that, as a frequent film critic for The New York Times. For my brother, there was also a vague personal connection by way of Yale Law (on top of being a reporter, essayist and film critic, Adler was also a lawyer) and around and about New York. And then there were those Avedon photographs. (Richard Avedon! Are you getting how breathlessly enraptured we were then?) In 1976, Renata Adler was happening.

The first part of the book came at us at a tear that seemed ripped from some script we had already memorized to perform in as participants in a family comic-documentary along the lines of An American Family (which was also a ‘thing’ around that time). Its opening is memorable – setting a kind of historiographic tone along the lines of an idiosyncratic Tale of Two Cities chronicle. But it lives up to its Evelyn Waugh flyleaf quote (from Vile Bodies) almost instantly.

Seventeen reverent satires were written – disrupting a cliché and, presumably, creating a genre. That was a dream, of course, but many of the most important things, I find, are the ones learned in your sleep. Speech, tennis, music, skiing, manners, love – you try them waking and perhaps balk at the jump, and then you’re over. You’ve caught the rhythm of them once and for all, in your sleep at night. The city of course can wreck it.

Followed by moments like these:

“To the Dow-Jones averages,” the father said,…

“Each in his own way,” the son said…. He was not a radical. He had been selling short.

And then a paragraph that resonated right then and there against the backdrop of L.A.’s rock culture. Bear in mind Pearl was a record a lot of us took with us to school and listened to all freshman year – recorded at L.A.’s own Sunset Sound.

Alone in the sports car, speeding through the countryside, I sang along with the radio station, tuned way up. Not the happiest of songs, Janis Joplin, not in any terms; but one of the nicest lines. “Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.” In a way, I guess.

You might well be in a speeding car (not a taxicab, by the way), or possibly an actual speedboat (though this through-motif is slightly more elusive – even inasmuch as it’s sketched faintly in the book’s first pages), as these images, these mid-stream slices of life, raw consciousness in a range from the vague and miasmic to the acute and crystalline, vignettes, memories variously close and distant, anecdotes never quite finished, private thought bubbles, and observations, both of the straight-on and rear-window varieties, fly at us relentlessly. That’s the pace of the book, and also suggestive of its elliptical structure – a quality shared with many contemporaneous novels. The period of the book, as much as it can be pinned down, is the time of its writing — the late-1970s cultural, political, economic hang-over following the ferment, upheaval and mass-culture renaissance of the decade between 1960s and the early 1970s. Social, political and cultural structures were decaying and collapsing under various pressures, or simply falling into disuse. And Adler was clearly conscious of the social/cultural dissonance and discontinuities as she ranged far afield of the Manhattan and Brooklyn landscapes, into the academic outposts, foreign capitals, caves, seaports (also ski resorts), and “Islands” (a chapter title), among other locations. You spend a lot of time ‘shuttling’ in this novel.

Fast forward 40 years later, and I learn of the second of Durden & Ray’s “Book Club” group shows curated by Steven Wolkoff – the premise being to take a book regarded (then or now) as particularly ground-breaking (which in fact Adler’s book was at the time it was published), and offer a group of artists opportunities to have at and flesh out various aspects of the book – themes, motives, incidents, characterizations, or other dimensions – and/or their contemporary relevance/resonance or broader cultural implications.

Fast forward 40 years later, and I learn of the second of Durden & Ray’s “Book Club” group shows curated by Steven Wolkoff – the premise being to take a book regarded (then or now) as particularly ground-breaking (which in fact Adler’s book was at the time it was published), and offer a group of artists opportunities to have at and flesh out various aspects of the book – themes, motives, incidents, characterizations, or other dimensions – and/or their contemporary relevance/resonance or broader cultural implications.

So … well that sounds great. In fact, the novel was resurrected and re-published only a few years ago (though having already read it, I didn’t pay much attention), so I could understand why artists, creatives and other audiences might be picking it up again. But, uh … an art show??? And then I started thinking about the book … or what I could remember of it … which was … not much. I poked around my apartment for the book; and quickly realized it had probably disappeared along with the two or three thousand other books I’ve lost over the last few decades. I called my brother first. No answer. I then called a New York producer l’d gone to school with who (then and now) shared my literary enthusiasms and preoccupations, and pitched the question. ‘Remember Renata Adler’s Speedboat?’ “Uh-huh. What about it?” ‘Uh, … what’s it ABOUT?’

It was as if I’d dreamed it and forgotten to write it down. I’d ‘caught that rhythm in my sleep’ once; and now apparently several intervening cities (though here I was back in the Los Angeles where I’d first read it) had ‘wrecked it.’ Finally, I called artist Dani Dodge, who is included in this show, a primary mover behind it, and generally a force of nature – who came to my rescue.

It was as if I’d dreamed it and forgotten to write it down. I’d ‘caught that rhythm in my sleep’ once; and now apparently several intervening cities (though here I was back in the Los Angeles where I’d first read it) had ‘wrecked it.’ Finally, I called artist Dani Dodge, who is included in this show, a primary mover behind it, and generally a force of nature – who came to my rescue.

There is something of a protagonist in the character of Jen Fain – a journalist with various, dubious berths in and out of the city; but her silhouette is as elusive as any other character.’ Unlike the protagonist of Adler’s Pitch Dark, she’s nothing of a ‘shadow’ or alter-ego to Adler; and in re-reading it, I have to wonder if she was vaguely modeled after someone like Nora Ephron or Fran Lebowitz. But then, this was a life so many of us were living or aspiring to live at that time.

Is it even possible to call it a novel? This is a question largely asked and answered emphatically in the affirmative. But the very fact the question remains even notionally open, the fact of the novel’s rediscovery in recent years, makes the notion of an art show – the most expansive art show possible – and this is exactly what Wolkoff and company have conceived – irresistible. That Wolkoff has seen fit to include every manner and category of artistic, cultural and creative production reflects a thorough understanding and terrific insight into the structure and diverse textures of the book. This is a book that moves at warp (and woof) speed spatially, temporally and psychologically through a blistering range of places from the geo-physical world to the most abstracted spaces of pure consciousness. Naturally this encompasses music (composer Michael Webster), body and performance (Choreographer Ania Catherine has conceived an original performance for the opening), and architecture (Jayna Zweiman – creator of the Pussyhat Project and Welcome Blanket). It also includes a toy designer (Dave Bondi), hair stylists Traci Sakosits and Matthew Kazarian (I’m hoping Adler’s signature braid will be represented), and mixologist Robin Jackson (the always essential libation-bearer).

Is it even possible to call it a novel? This is a question largely asked and answered emphatically in the affirmative. But the very fact the question remains even notionally open, the fact of the novel’s rediscovery in recent years, makes the notion of an art show – the most expansive art show possible – and this is exactly what Wolkoff and company have conceived – irresistible. That Wolkoff has seen fit to include every manner and category of artistic, cultural and creative production reflects a thorough understanding and terrific insight into the structure and diverse textures of the book. This is a book that moves at warp (and woof) speed spatially, temporally and psychologically through a blistering range of places from the geo-physical world to the most abstracted spaces of pure consciousness. Naturally this encompasses music (composer Michael Webster), body and performance (Choreographer Ania Catherine has conceived an original performance for the opening), and architecture (Jayna Zweiman – creator of the Pussyhat Project and Welcome Blanket). It also includes a toy designer (Dave Bondi), hair stylists Traci Sakosits and Matthew Kazarian (I’m hoping Adler’s signature braid will be represented), and mixologist Robin Jackson (the always essential libation-bearer).

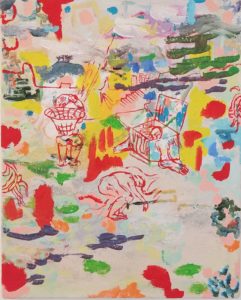

A host of other well-known visual artists further flesh out the novel’s textures, including Jennifer Celio, Dani Dodge, Tom Dunn, Kio Griffith, Jenny Hager, Ben Jackel, Laura Krifka, David Leapman, and Liza Ryan (whose work to date has frequently navigated physically and psychological complex passages). This is a group richly equipped to turn the situational conundrums, dream logic, and lightning-flash insights of Adler’s novel into a cosmic disturbance equal to its mark on the literary landscape.