In the mainstream, queerness has a way of being pushed into the shadows, forced back into the closet. It happens all around us, especially in communities of color, spaces which still oftentimes say that queerness does not belong here. It was a bit of a surprise then to see queerness so unabashedly out this fall as part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, the massive exhibition series funded by the Getty Foundation focusing on Latin-American and Latinx art.

That the three exhibitions that sought to emphasize this queerness specifically focused on the city’s Chicanx community is worthy of note. Often raised, as I was, against a strong Mexican Catholic background, queer Chicanx people have historically struggled to gain recognition as artists working from a complex set of identities that at times can be at odds with each other. For that reason, it’s an experience that doesn’t fit neatly into either of the limiting predetermined categories of Chicano art or queer art (their intersections usually ignored and discounted). Despite this baggage, both art historical and societal, the curators involved with these three PST exhibitions did commit to tell these complex stories of Chicanx queerness—with varying degrees of success.

Installation view of “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” at MOCA Pacific Design Center, photo by Zak Kelley, courtesy of MOCA, Los Angeles, and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries.

The largest of these shows was the two-venue exhibition “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A.” at the ONE Archives Gallery and MOCA Pacific Design Center, both in West Hollywood, the city’s historic gayborhood. In their exhibition, C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz sought to highlight constellations of queer interactions happening across LA’s Chicanx art community and beyond, which often hid in plain sight.

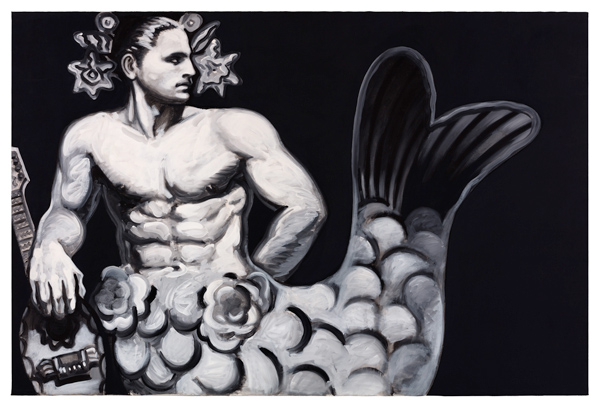

Mundo Meza, Merman with Mandolin, 1984, photo by Fredrik Nilsen

The curators chose Edmundo Meza, known as “Mundo” and the namesake for the exhibition, as a starting point and organizing principle between the other artists in the show. The show positioned Meza, an under-known artist who worked between painting, performance and fashion window displays, among other art forms, as the connective tissue between other lesser-known Chicanx artists and some of Chicanx art’s heaviest hitters: Carlos Almaraz, Gronk, Judith F. Baca and Laura Aguilar. By doing this, Chavoya and Frantz illuminated just how connected queer Chicanx artists were to each other.

Mundo Meza, Sweet, 1975, ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries, Courtesy of Pat Meza, photo by Fredrik Nilsen

One major surprise of the show was the inclusion of gay artist Ray Navarro, best known for dressing up as Jesus Christ during ACT UP New York’s protest outside of St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Because the final two years of his life were spent in New York, where he moved to attend the Whitney Independent Studies Program, Navarro is often thought of as a New York artist, whose practice focused on the realities of the AIDS epidemic. But his connection to the overall group of artists here—attending Otis and exhibiting at Self-Help Graphics & Art, both hotbeds for Chicanx artists—is significant, and further demonstrates the ways in which Chicanx artists often have their personal biographies whitewashed as the price of being accepted into the canon, since accepted AIDS Art has historically been dominated by white, cisgender men, like David Wojnarowicz and Keith Haring.

Ray Navarro (fabricated by Zoe Leonard), Equipped, 1990. Collection of Patricia Navarro. Photo by Zak Kelley. Courtesy of Patricia Navarro.

Navarro is represented in the exhibition with Equipped (1990), a triptych of gelatin silver prints showing a wheelchair, a walker and a cane, items Navarro used to help with his mobility as HIV ravaged his immune system. The photographs, done in collaboration with artist Zoe Leonard, are accompanied by metal plaques that add a dark humor to the realities of Navarro’s final months: the text below the almost phallic cane, for example, reads THIRD LEG. The piece, like many produced by those lost too soon to the epidemic, is harrowing for its power and directness. The work also helps to further contextualize Leonard’s seminal 1984 poem that includes the line “I want a person with AIDS for president,” expressing a desire for someone who has experienced marginalization and being othered to lead.

:::

Carlos Almaraz, who had several minor works, collages and watercolors, in “Axis Mundo,” (mostly from the 1970s) was also the subject of a monographic exhibition at LACMA as part of PST: LA/LA. The introductory text to the exhibition seems to present itself as an attempt to revisit Almaraz, considered one of the leaders of the Chicano art movement, and his artistic legacy, including a forthright discussion of his bisexuality. While these moments of recognitions of queerness are breakthroughs in their own right and cannot be discounted, curator Howard Fox does not go far enough with his attempted repositioning of Almaraz.

Carlos Almaraz, Crash in Phthalo Green, 1984, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the 1992 Collectors Committee, ©The Carlos Almaraz Estate, photo ©Museum Associates/ LACMA.

In his catalog essay, Fox describes Almaraz’ mature art, the focus of the LACMA exhibition, as having a “fundamentally metaphorical nature.” In the next paragraph, Fox writes that Almaraz’ bisexuality was well known to his inner circle yet never openly acknowledged in relation to his art or even his personal biography, attributing it to “the repressive machismo of Chicano culture, as well as the broader cultural taboos that existed around being gay or bisexual at the time, particularly around HIV/AIDS.” Fox adds, “Almaraz’ public persona and his personal reality can be seen as constituting a kind of double life.”

But a discussion and analysis of how that “double life” and “fundamentally metaphorical nature” go hand in hand, particularly in the works he made in his final two years, after his HIV/AIDS diagnosis in 1987, was a missed opportunity. Fox shies away from placing Almaraz into the broader context of queer and AIDS art from the era. (A comparison between his small painting The Magician (1987) and Robert Mapplethorpe’s final self-portrait can easily be made.) It allows Almaraz to be out of the closet but with conditions. He can be bisexual, but not too bisexual.

Carlos Almaraz, Echo Park Bridge at Night, 1989, The Buck Collection through the University of California, Irvine. © Carlos Almaraz Estate. Photo by Isabella McGrath.

The exuberance of Almaraz’ fantastically painted scenes of Echo Park, which show that there is beauty in a historically Chicanx neighborhood, are in sharp contrast to his scenes of death and destructions. These two series, executed around the same time throughout the 1980s, show an artist of two minds, a man grappling with the realities of his bisexuality at the time that the AIDS crisis was being pushed to the forefront of the national conscience within the framework of a community dominated by an oppressive macho culture. The works, done in similar color palettes with rough applications of paint, share an aura of the fantastical and a pulsating energy, and can be seen more precisely as suggestions that perhaps it would be better if it all ended in the split second of a fiery car crash atop a freeway than in a prolonged death from HIV/AIDS. If we are to read metaphor into Almaraz’ works, how can metaphors around images of death not be mentioned in the same breath as an artist’s own looming mortality?

:::

Back at “Axis Mundo,” the works of lesbian Chicanas were also prominently displayed. Baca, best known as a muralist, is out in full force with color photographic documentation of her groundbreaking 1976 performance Vanity Table for the exhibition, “Las Chicanas: Venas de la Mujer,” which she organized that year at the Woman’s Building, the city’s locus for feminist art at the time. Seated in front of a vanity table, Baca looks directly into her mirror as she primps herself in the fashion of a pachuca, a Chicanx style of dress and culture from the 1940s. To an outsider, Baca’s high arched eyebrows, heavily rouged cheeks and bright blue eyelids might look grotesque, appearing as a caricature. Baca plays to these outsider opinions, knowing full well that the audience who would see the performance would be primarily the middle-class white women who dominated the Woman’s Building. But to the Chicanx community, Baca appears as beauty personified, a woman looking good and feeling good for no one but herself.

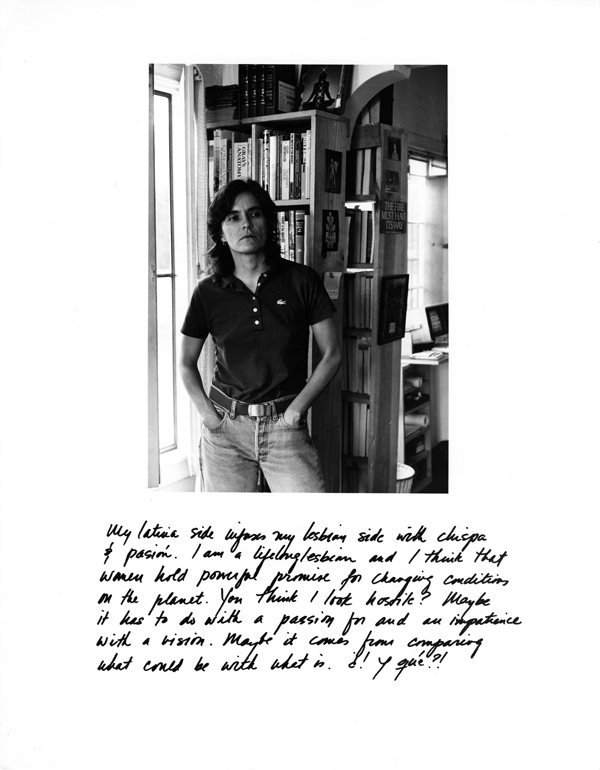

Laura Aguilar, Yolanda, 1987. From the Latina Lesbians series, 1985–91. Courtesy of Laura Aguilar.

Also on view were photographs from Laura Aguilar’s “Latina Lesbians” series, which pair strong-gazed black-and-white portraits of lesbian Latinas accompanied with handwritten notes describing their own unique lived experiences. That series, often painfully heartfelt, was on view in depth in the artist’s career retrospective at the Vincent Price Museum of Art, showing the true power of her still under-recognized artistry (reviewed in Artillery’s November/December 2017 issue). In one work, titled Yolanda, at “Axis Mundo,” the sitter describes how her Latina and lesbian inform each other. Of her direct gaze, Yolanda asks viewers if they think she looks hostile, countering with her own answer: “Maybe it comes from comparing what could be with what is. ¿¡Y qué!?” So what, indeed. It is in this no-fucks-given attitude, implied in the original Spanish, that queer Chicanx artists create work and build networks, communities and chosen familias of their own, on their own terms.