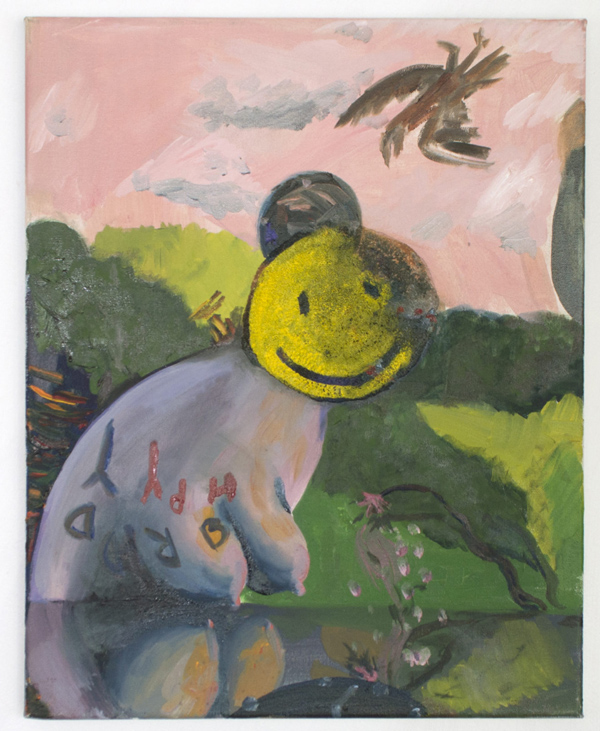

In Andi Magenheimer’s “HpPy BRdDY,” a smiling and limbless dinosaur’s engorged human breasts graze the reflecting water below, imperturbably still while a rhododendron sheds its petals endlessly from the shore, the sunset curving into and around the creature’s confused but recognizable shoulder, the fading daylight nearly Tumblr pink but more distinctly rose, and more distinctly aging; a bird is neither flying nor resting above, frenetically targeted downwards but not yet swooping, frozen, frankly disease-ridden, and the letters: “H-P-Y-Y B-R-D-D” are tattooed on Harvey Ball’s oblong Venus, or floating—they’re vampiric either way, this immaculate reproducing body of water underneath not capturing their majuscule form.

Message and delirium are swashbuckled in the work into a portrait of a moment that neither begins nor ends—could never begin and end—and yet feels tangible, as though this reality exists only as it is conceived of and emphasized in this exact way, cartoonish but either unexasperatingly or garishly truthful. In some sort of broader sense this is the premise of image making, the Wittgensteinian: “A picture depicts reality by representing a possibility of existence and non-existence of states of affairs“ (from the Tractacus).

Kissing Interactions

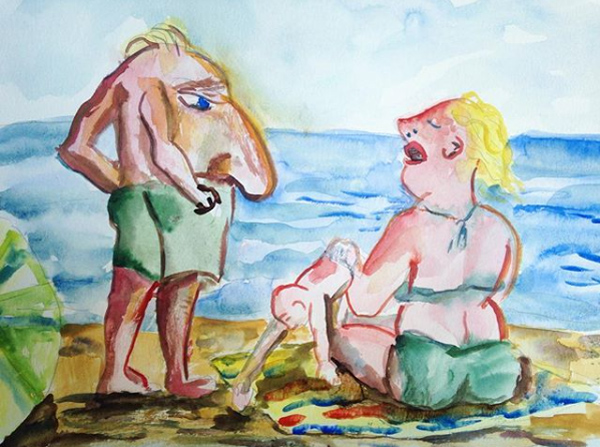

The representation of the non-existence of states: Lee Lozano pictured a woman’s pubic hair encircling instead an electrical outlet that is nearly penetrated by the prongs of a toaster’s power supply in “Toastadora.” Magenheimer connects a brown pinscher’s tongue to a turtle’s asshole, the tongue winding out, extending fictively to bridge the gap of muci, and then archives the impossibility as one in a series of “Kissing Interactions.” These are not non-existences, these are super-existences or sub-existences, a reality that is so obvious—yes, of course—and yet so foreign. In “Beach Scene,” a man, probably a father, consists of a gigantic nose in place of a belly and eyes on the pit-sides of his pecs, like a bizarre demersal fish, a thin plot of hair around his neck, head absent, his hand on his waist, presumably now where his mouth begins, or perhaps his shorts still hide a little penis; a woman, probably a mother, speaks matter-of-factly or calmly prepares to sneeze. Her hand is either on the bottom of or inside a child, who is splayed forward from her lap; or maybe he spawns outward from the hand—his legs are tricky to place—of the blond woman, with her blond deformity of a companion. The point of intersection is as ambiguous as the child’s legs, in this case blended or colored with what would seem to be a single quick jab. Maybe the child is a she, just bald and too young to gender. The child could be focused—actually seems transfixed—but could just as well be resigned and displeased; there is the option of comorbidity. Its mouth is hooped into a “Oo” shape—it could be drooling, if its lower jaw is absent, more of a spittling, noiseless grunt: “Oogh. This was apparently painted in Charlestown, Rhode Island, although that could be meant to indicate the subject matter.

The largest archive of Magenheimer’s work is Instagram, where the soundness or reliability of information becomes a game, one she plays well.

The first time one sees “The Indian Sign“ by Jon Serl, if one ever sees “The Indian Sign“ by Jon Serl, a painting that features an impish child scrawling a backwards swastika, a sauvastika, onto the bare skin of a woman’s (again, probably a mother’s) back, the skin revealed not through a tear in the woman’s pale yellow dress but an opening, a hole, both figures next to an eerie, somewhat nuclear barrel, a portrait of a specter hanging near the woman’s veiled buttocks, like an empty horned ski mask, maybe an animal, candles on the shelf above, the mother’s face visible through the mirror, an exemplar of a face, looking at herself, or us, her hands running through or tearing at her knotted brown hair—here is this same trajectory of disorientation, uncertainty as to whether what you are looking falls in line with any prospect of taste or coherence and then complete bedazzlement, that anything could possibly have so accurately represented something you’ve known for so long. That is the success of Magenheimer’s work: it plunges the viewer into the uncanny valley of this sub-reality, the uncertainty of whether these images represent a possible existence, or the nonexistence of states of affairs, and into the wretched comedy of confronting the unanswerability of such a question.

Moon Dog

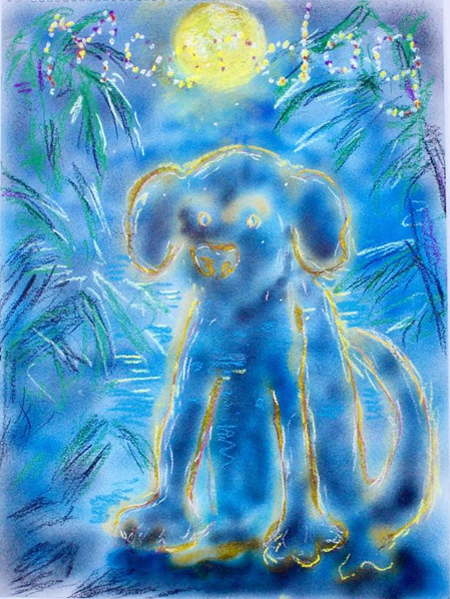

In “Moon Dog,” in acrylic pastel, blended to the point of feeling almost airbrushed, the golden outline of a dog appears surrounded by tropical reeds and palms, an apparition on the black rocks that lead out into a calm bay, the witching hour, the high tide nearly reaching the spirit pup’s gilded and supernatural paws; two beads of light between the short pendant ears look both towards and beyond, curious and alert but unfrightened. “M-O-O-N-D-O-G” is spelled out in energetic luau or lei letters, backlit by the massive yellow moon.

The dog—Luna—looks similar to one of my two favorite stuffed animals growing up, Schmutzy, a variation of the originally Yiddish “schmutz,” which means dirt, filth, or garbage according to the Random House Dictionary. In an objective that necessitates faking it all of the time—I’m faking it, I’m faking everything—through every moment, for fear of being schmutz, I am glad that the ghost of my stuffed dog is in one of Magenheimer’s drawings. There is no critical discourse to be piled on top of Moon Dog: there’s an ethereal dog in this reality, I like that Magenheimer is portraying these things, and happily you sometimes don’t speak to that; you just leave it floating.

Magenheimer’s most recent exhibition, “Truck Full of Feelings,” was on display this October and November at Gallery Sensei in New York.