Mimi Pond is a legendary figure in LA—part of the generation of independently-minded cartoonists nurtured—then dumped—by the alternative media, she also wrote the first-aired episode of The Simpsons (before being expelled from the bullpen) as well as contributing to Pee Wee’s Playhouse alongside her artist husband Wayne White.

Pond’s public image has recently made a quantum leap in the shadow world of graphic novels, with her acclaimed 2014 fictionalized memoir Over Easy, which detailed her day-to-day social adventures after dropping out of the CCAC and getting a job as a dishwasher—soon waitress—at a nearly post-hippy diner in Oakland in the late ’70s.

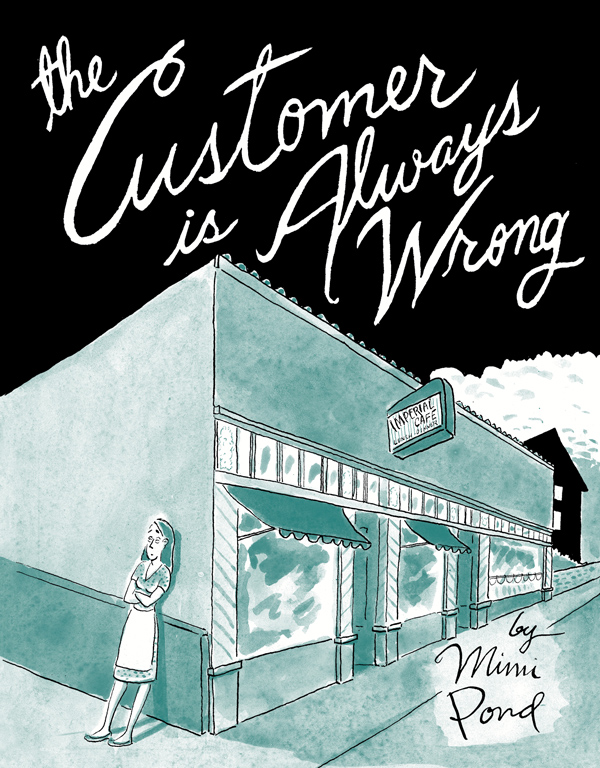

Her new volume, The Customer is Always Wrong, picks up exactly where Over Easy left off—vibrating between laid-back hippy self-mockery and seething punk rage. Although the saga of art-school dropout Madge and the colorful cast of Bay Area lowlifes with whom she consorts were apparently split into two for completely logistical reasons, the bifurcation is fortuitous.

The Customer is Always Wrong, cover

Where the first volume chronicles a relatively idyllic period of compromised innocence—sex, drugs, and rock & roll in other words—the sequel delves into more challenging bardos, depicting beatings, murders, heroin ODs, and abortions with the same light attention as the awkward romances and naughty experimentation in Over Easy.

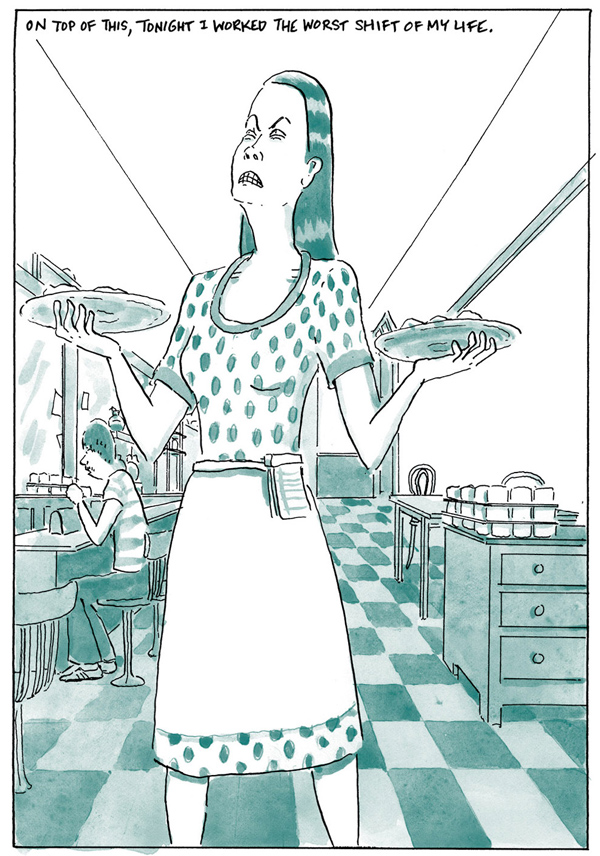

Pond’s lightness of touch is twofold, evident in both her artwork and narrative gifts. Her relaxed, economical black ink line—augmented by judiciously deployed washes of blue—conveys an archetypal bohemian vibe that immediately sets the tone for Madge’s subterranean journey, and is stylistically supple enough to accommodate anything from lyrical interludes to car-chase sequences.

The Customer is Always Wrong, p. 96

Her fondness for Edward Hopper—mentioned several times in the story—is evident in her carefully observed urban landscapes and architectural interiors, while her characters owe something to the deceptively loosey-goosey renderings of Roz Chast and the frenetically exaggerated body language of Lynda Barry’s Ernie Pook (though Pond’s official mentors were from her time at NatLampCo—Shary Flenniken of Trots and Bonnie fame, and the criminally under-recognized surrealist genius M.K. Brown).

Her writing is equally fluid, shifting from contemplative interiority to slapstick humor in the space of a few panels, focusing in for microscopic views of inner monologues, then pulling back to take in the bittersweet sociopolitical uncertainties of this particular time and place—ground zero of the ’60s counterculture at the point when it was staggering on its last legs.

Over Easy, cover

Perhaps the strongest aspect of the story is its characterizations, building up a dozen or so complex central personalities with layers of nuanced observation, and sketching out twice as many with broad but incisive strokes. Lazlo, the manager of the Imperial Cafe, is the central figure of the narrative: a fun-loving, substance-friendly hepcat family man; a disgraced Latin scholar-cum-poet who glories in—and orchestrates—the absurdist chaos of the faltering utopian macrocosm surrounding him.

The narrative engine of the two-volume 700+ page epic is the gradual erosion of the tiny model anarchist society Lazlo has created from (and for) the various outcasts and misfits that populate the cafe, as his family life and other real world concerns increasingly intrude on his carefully crafted alternate universe.

Equally impressive is Pond’s quasi-self-portrait, which functions like a set of incrementally less judgmental nesting dolls—Madge the character is frequently exasperated by the coke-fueled antics of the greasy spoon brigade, while Madge the narrator has clearly learned (from Lazlo, it becomes clear) their value as players on the stage of life. Mimi, the invisible architect, cherishes each quirk and flaw as precious facets of her own reconstruction of Lazlo’s world.

The Customer is Always Wrong, p96

Throughout, storytelling is held as the highest good—not just in the exquisitely shaggy authenticity of Mimi’s meandering plotline, but repeatedly in the characters and dialog. One of Madge’s most annoying nemeses is a customer called Neville—a Canadian punk with a fake cockney accent who only redeems himself with his outrageous and plainly fabricated globetrotting autobiographical anecdotes.

This is the real moral of The Customer is Always Wrong above and beyond any free love/expensive cocaine hangover. Very early in the story, Lazlo breaks the fourth wall—speaking to Madge during her job interview, but looking directly into the reader’s eyes, saying “Tell me a joke. Or a Dream. If I like it, I hire you. That’s the way it works.” Several hundred pages later, Madge is about to move to New York and throws herself a going away party.

Madge and Lazlo are on the porch, palavering for the last time. The conversation is weighty and philosophical, and addresses storytelling head-on. “Every day is full of marvels,” Lazlo observes “Everything is struggling to be part of a story.” Then, having by this point stopped using drugs and alcohol, he speculates at length about whether language isn’t just another form of escape, and the conversation grinds into a discursive cul-de-sac.

After an existential heartbeat, Madge remembers a story about a decrepit regular at the diner, and tortured Lazlo lights up—launched from his verbal torpor and encroaching troubles into a full-throttle gale of laughter, from the vicissitudes of Time into the mythological mundane. Sometimes it pays to bullshit a bullshitter.

Images provided by Mimi Pond & Drawn and Quarterly

Over Easy (2014)

272 pp

The Customer is Always Wrong (2017)

448 pp

Drawn & Quarterly, Montreal