The Red Shoes (1948) is perhaps the most famous dance film of all time. Sumptuously shot in Technicolor and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger in post World War II England, it was one of those backstage dramas so popular then, when audiences romanticized the glamour and passion of those who worked on and behind the stage. Theater people were seen as larger than life. They loved more, hated more, sang and danced more, and every day was high drama—the stuff of the Big Screen.

The new dance version of The Red Shoes by Matthew Bourne which opened last week at the Ahmanson Theatre is a dazzling reinterpretation. There’s gorgeous production design and stagecraft, effervescent dancing, and considerate wit. Bourne fearlessly changed elements he thought would enhance and differentiate his retelling. And yes, some of the nuances of the film have been lost, because dance is a different medium from film, and cannot do what a film can. (I am a huge fan of the film, and of course took this excuse to re-watch it again.) On the other hand, the sheer joy and immediacy that can be conveyed via live performance is conveyed here, this new performance.

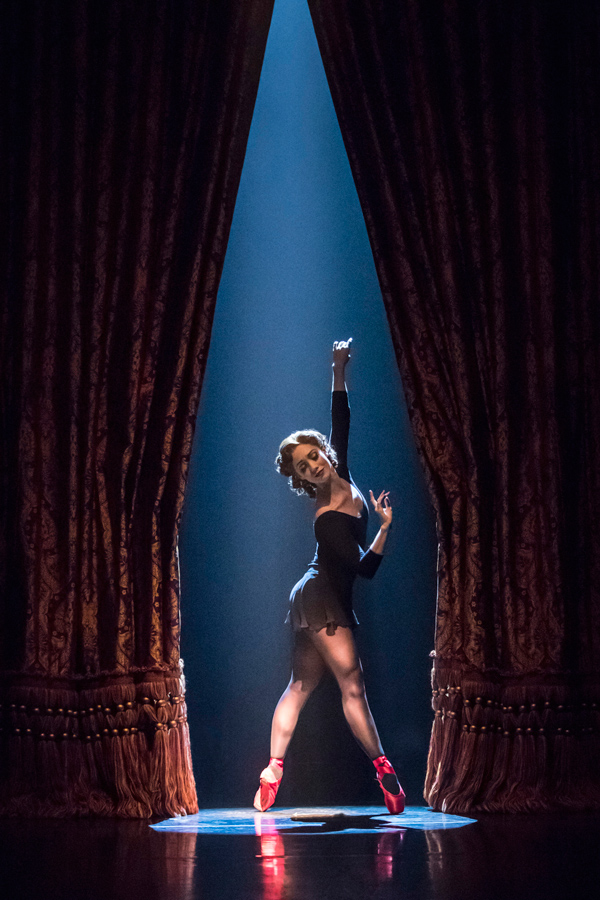

Ashley Shaw, photo by Johan Persson

The story pivots around a beautiful young dancer, Victoria Page (played by Ashley Shaw), who is plucked out of the corps de ballet by imperious ballet impresario Boris Lermontov (Sam Archer) to star in his production of The Red Shoes. His inspiration, as was the inspiration for Powell and Pressburger, is Hans Christian Andersen’s fable of a young girl who falls in love with a pair of red shoes and begins to dance—and dance and dance and dance. In the end she cannot take them off. Andersen’s story is a Christian parable, and tells us that she has sinned by shirking her duty to care for her patron and going to go to a ball, with her red shoes, instead. For that transgression she will be sorely punished. The movie drew the parallel between Vicky, who is obsessed with dance, and the protagonist of the fairy tale, but updated her motives—Vicky loves dancing, not just as some hedonistic sport, but as a deep artistic calling. However, she ends up falling in love with the young composer of the ballet, Julian Craster (Dominic North in the Bourne version), and ultimately she must choose, love or art. In the meantime, the story takes us quickly from London to Paris to Monte Carlo, with some charming ensemble scenes of rehearsals and of dancers smoking and strolling along the Riviera.

Ashley Shaw and Sam Archer, photo by Johan Persson

Shaw and North were both delightful dancers, with much youthful expressiveness as they twirled across the stage. Archer as Lermontov struck the right haughty poses, often turning his head in profile to let us admire his chiseled chin. As a dancer, however, he was rather stiff. And in the scene where he expresses his torment over losing his protégée, he does some Martha-Graham-style contortions that bordered on parody—was that the intent? To me it detracted from real empathy with his grief—and in the film, Lermontov (in a superbly chilling performance by Anton Walbrook) is almost sympathetic, because his grief is palpable.

Sam Archer (left) and the cast of Matthew Bourne’s production of “The Red Shoes.” Photo by Johan Persson

The use of a rotating proscenium on stage is brilliant, becoming sometimes a curtain, sometimes a divider, sometimes showing us the play-within-play performance, then turning around to put us backstage. Another achievement of Bourne’s production is to ditch the original score (which was too short, anyway) and use instead the lush and emotional music of Bernard Herrmann, as adeptly arranged by Terry Davies. Herrmann, of course, is known for his many collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, but much of the music repurposed for The Red Shoes was from Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane!

Ashley Shaw, photo by Johan Persson

However, I am a bit disappointed that the new ballet has reduced the film’s sexual politics. For film scholars The Red Shoes has been held up as case study of the impossible choices women are offered—Vicky has to choose either traditional love/marriage or work/career. In the film Irina Boronskaja, the prima ballerina, leaves the troupe because she is getting married, and Lermontov brushes her off, saying, “I’m not interested in Boronskaja’s form, anymore, nor in the form of any other prima ballerina who’s imbecile enough to get married.” In the Bourne version, Irina is put out of commission by having an accident during rehearsal and has to sit out performances in a cast. At the end of the film Vicky goes back to dance with Lermontov in a revival of The Red Shoes, and Julian shows up to demand she come back to him—so possessive is he that he’s actually skipped the debut of his own opera back in London! The movie Julian is a conceited little twerp prone to temper tantrums. The Bourne-version Julian is a pleasant enough young fellow. When he has a spat with Lermontov, Vicky just naturally goes back to England with him. At the end there’s literally a tug of war between Julian and Lermontov, with Vicky pulled between them, although it was unclear whether this is “real life” or part of a nightmare.

Yes, do go see Bourne’s The Red Shoes—it’s one of the most beautifully realized pieces of dance and of stagecraft to come along in some time. Then check out the DVD of The Red Shoes and savor that, also.

Matthew Bourne’s The Red Shoes (through Oct. 1)

Ahmanson Theatre

The Music Center of Los Angeles

For tickets: Call 213 628 2772 or see www.centertheatregroup.org