Sporting an orange kaftan shirt and a wide-brimmed black hat perched atop his head, poet Stephen Kalinich looked more like he was ready for a wild trip than for a reading.

“I, the poet, write this plea to the world,” he began the evening, noting that he first read this line in 1968, in the midst of the Vietnam War, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the seeming demise of America.

Stephen Kalinich reads from his selection of protest poems.

Now, in times when many of the non-political find themselves anew in activism, Kalinich felt compelled to make a poetic statement against injustice. His far-out look didn’t detract from his rallying cry for peace which he disseminated among the older art crowd at L.A. Louver gallery in the heart of Venice Beach on August 23.

Earlier this month, the poet and Beach Boys collaborator read a series of protest poems, first written in the late 1960s and 1970s, followed by a performance by Los-Angeles-based, non-hierarchical music collective known as Divinity Band.

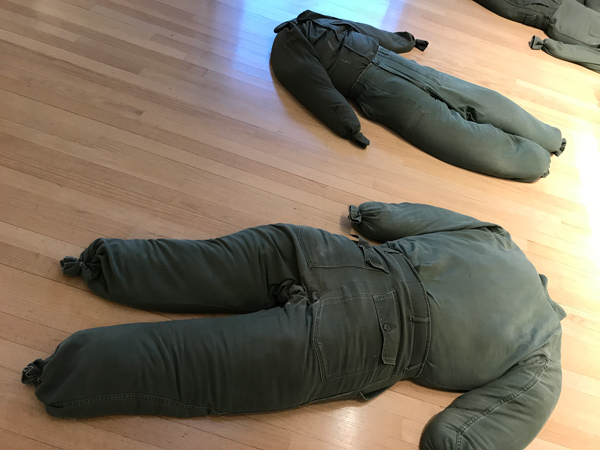

Edward Kienholz’ ceramic corpses lie in front of his “Non War Memorial.”

The performance, “Night of Protest Songs,” was held alongside L.A. Louver’s ongoing exhibitions, Ben Jackel’s “Reign of Fire” and Edward and Nancy Kienholz’ “The Non War Memorial,” “Still Dead End Dead” and “The Jungen.”

Amidst poetics and music, guests were encouraged to stroll about the gallery, pondering Jackel’s ceramic and wooden sculptures of war, covered in an ominous sheen of graphite or Kienholz’ disturbing lifeless figures, splayed on the floor in military dress as if freshly killed.

Though many seemed to be jiving with Kalinich’s universal message as the violence and wars of the past resurfaced to the room, I could not help but find his prose to be entombed in the political platitudes of the past, falling on already sympathetic ears.

So it goes, I suppose, a reading right in the changing heart of left-leaning Dogtown—the revolution may not happen here, not now. But at the very least, it is on our minds.

Ben Jackel’s ceramic fleet of cannons and fighter jets.

However, the Divinity Band, a five-person band, verging on anarchy with their refusal to own their music and their ever changing membership, left much up to interpretation with their non-vocal distorted, improvisations.

Each musician carved their own path whether by guitar, bass, electric harp or synthesizer. Together the dissonant rhythms, though imperfect and crooked, propelled me into the present.

I mounted L.A. Louver’s upper level to view the “Non War Memorial” and moved out to the patio—a white box facing the boundless blue sky—to experience a moment of solitude with the music and Kalinich’s words.

Momentarily in that private place, walls adorned with silence and the sky above as my only witness, I felt intoxicated with the now, with the discord in the music heard below, the possibility to begin again and the always incomplete articulation of revolt.