“What’s with the God look?” I had thought to ask him at one point over the course of a rambling interview conducted in the lead-up to LACMA’s opening of his retrospective—provocatively, ironically titled, “Pure Beauty.” A slightly exaggerated (to say nothing of irreverent) take on a persona which is, after all, pretty familiar to most people who frequent Los Angeles art galleries, and indeed almost anyone acquainted with contemporary art around the world. But there is only so much time for irreverence in the company of an artist of John Baldessari’s stature.

At 6 feet 7 inches, that might be half the story right there. Public perceptions of Baldessari’s persona or public image may have evolved more or less in step with his career, a kind of reinvention that might be expected to parallel the invention of a new kind of art: from artist-teacher-malcontent to the self-radicalized, self-reinvented artist-professor-mentor; the local artist with an aggressively global outlook; and finally an avuncular figure become anchor and authority for an agglomerate of disparate styles and movements now commanding the global art market.

Baldessari’s own position in the global marketplace belies the extent of his influence; the auction records for his work do not approach the stratospheric levels of say, Koons, or for that matter, his conceptualist peer, Bruce Nauman. But even Baldessari’s “conceptualism” (if it can even be called that any longer) has always had a “left-coast” catholicity and eccentricity that set his work apart from his more ideologically entrenched peers (e.g., Kosuth)—a factor that has been crucial in the evolution of his art, as well as its broad influence. Ironically, as reluctant a teacher as he was, it is perhaps his role as mentor to a remarkably diverse group of artists that has extended and magnified his influence and importance. In other words, as important as his work is, it is not for that alone that he remains such an important figure in the post-modern contemporary landscape.

His reticence to discuss his teaching or mentoring of this flock of students is initially off-putting. Yet over the course of an interview that veered wildly between shallows and depths, one began to sense that, just as the “voids” in his art can be as important as the visualized elements, what Baldessari doesn’t say is as important as what he does. Speaking of his early videos, many of which were made in conjunction with his earliest teaching at CalArts, he insists, “I didn’t teach; we didn’t have any formalized courses. I mean, it [the Sony Portapak video cameras] was there; so I was learning along with the students … Everybody was experimenting because there was nothing to learn. You were charting your own course.”

Yet even here, Baldessari limns a definition of a particular brand of conceptualism which, though it had already taken recognizable shape in some of the original text paintings, text-and-image pieces, early photography and the “Commissioned Painting” series executed between late 1967 and 1970, gave a wide berth to an extensive range of media, artistic or visual strategies, and expressive possibilities. Asked whether he could single out any of his students who made particularly original or inventive use of that license to learn, from classes that included, among others, David Salle, Troy Brauntuch, Jack Goldstein, James Welling and Matt Mullican, Baldessari insists he “can’t pick anyone out. I’d encourage any student to believe in themselves and not mirror other art that they see.” Baldessari speaks more expansively about his teaching/not teaching in Richard Hertz’s oral history, Jack Goldstein and the CalArts Mafia. “I don’t think you can teach art, but you can sure have a lot of good artists around.” But on a facing page, he takes a much more purposeful stance. “Good teaching is giving students a vision. I wanted to ignite a fire in their eyes.” Having once encouraged his students to leave LA for New York, Baldessari is unfazed that many of his former students moved in directions well beyond his own generous conceptualist and post-conceptualist ambit. “They wouldn’t be good artists if they didn’t.”

In spite of the fact that he once said “If I saw the art around me that I liked, then I wouldn’t do art” Baldessari clearly admires a number of contemporary artists, including many well outside the post-conceptualist vein. But you wonder if the only place he’ll admit this is at a gallery or museum opening for one of them. Pressed to “name names,” he offers only the opinion that “Sigmar Polke in Germany is an incredibly inventive person.” Baldessari concedes, “There are a lot of artists I admire; I could go on and on.”

Polke garners a second mention somewhat later in this interview, which underscores the sincerity of Baldessari’s admiration. For an artist of his exalted standing, he can be almost infuriatingly circumspect, even cagey, about his likes, dislikes, enthusiasms, inspirations and opinions. In discussing the matter of galleries and dealers (Baldessari has been blessed with outstanding representation on both coasts), the subject of New York gallerist Jeffrey Deitch’s appointment to the directorship of MOCA is broached, and Baldessari stiffens a bit. “I probably shouldn’t say anything. I’m on the Board of Trustees — I’ll say that.” Pressed on grounds of increased transparency in MOCA’s administrative governance and executive oversight, he will admit only that “it was the decision of the Board to hire him, and I hope it all goes well. I mean that’s all you can say.” Which may say less about the incongruities and ambiguities between words so much a part of his working M.O., than the political softball of the LA art world.

Baldessari can be vague about his working means and methods (though he has occasionally been forthcoming in the past). It is true that his acquisitions of old movie stills and commercial photography have been relatively random or simply opportunely timed. He admits to having a special liking for film noir images, but quickly amplifies that he was never after movie stills, per se. “They were just collected as cheap visual imagery, which is something I’m interested in; and since I could get them so cheaply, if I found something interesting, I would buy it and think about it later.” But when asked about his methodology in selecting from his well-catalogued image bank and orchestrating the sequences, juxtapositions, and selective obliterations that are trademark components of his work, he volunteers nothing. “Intuition, I guess. How do you go about putting two words or sentences together? They either go together or they don’t.”

On the other hand, addressing the signature voids and obliterations more specifically—the (sometimes colored) dots and voided elements or silhouettes—Baldessari seems aware that their appearance signals his authorship, and acknowledges that “it’s something that seems to be fundamental to a lot of what I do.”

“I think viewers are pretty sophisticated. You don’t have to tell them everything. And I’m interested in hierarchies of looking at things. So if you had a very important-looking person—or not, just a person—I think we tend to look at a person’s face first, rather than their elbows, toes, or whatever. What I try to do is jostle that order and eliminate the most important things, and show the least important things; and I think that this jogs you into a new way of looking at things.”

Baldessari’s rationale applies more convincingly to the reconfigured, arguably redirected, movie stills. Some of his most famous photo-collages from the mid-1970s and well into the 1980s feature both well-known and sometimes very expressive faces (e.g., Chicago’s most famous mayor, Richard J. Daley, in Brutus Killed Caesar), yet remain clearly subordinate to their controlling metaphors. Baldessari’s admiration for Godard to one side (he once called Godard a “more important visual artist than Jasper Johns”), he is no film director manqué. But he is conscious of “setting up a narrative.”

As willfully disconnected from aesthetic considerations as Baldessari claims to be — and certainly some of his earliest conceptual work minimizes the aesthetic dimension (even as it asserts fine art status)—his work from the mid-1980s (and arguably earlier) has an aesthetic that seems to derive precisely from his interest in the “hierarchies of looking at things.” While he claims that even the use of color for his dots and voids was intended to be “non-aesthetic,” to function as “pure signal—red might be something dangerous, green might be something safe,” he accepts that “no matter what you do, it’s still going to look beautiful—you can’t escape it.”

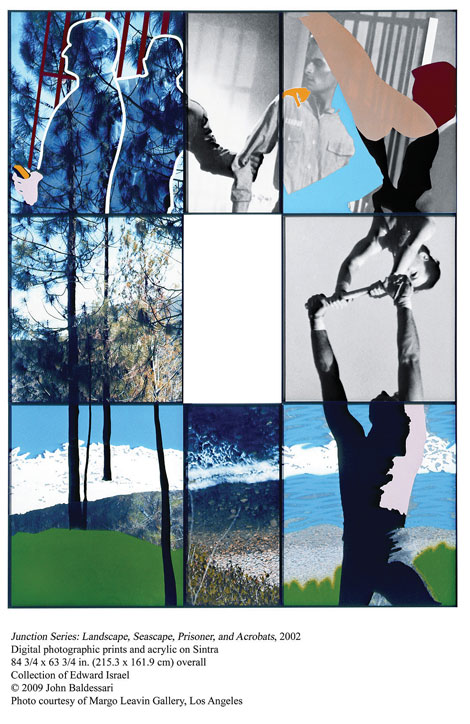

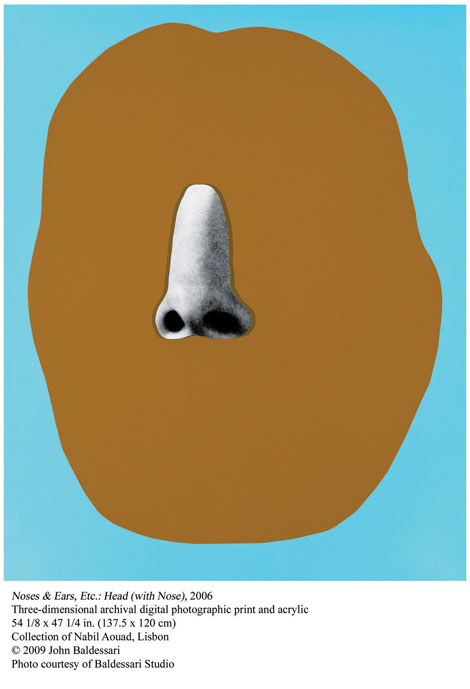

More recently Baldessari’s gestural dissections, reconnections and reconfigurations have given way to new fragmentations and dislocations (e.g., dislocated or displaced noses and ears). “It’s all about editing—what the person decides to put out or not put out there to the spectator or viewer. And there’s no sense visually in showing everything about a figure if all you want to do is talk about the presence of a figure. I mean, look at all of the movies you’ve seen now—you’re being very carefully manipulated. Artists do that, too.”

For someone only casually acquainted with Baldessari’s career history, “connecting the dots” can be elusive. Just as Baldessari’s early text paintings and photo-emulsion canvases played—“didactically” or conceptually—on wrong or false teaching or misconceptions, Baldessari’s information-based art has seemed to evolve as much into an art of disinformation or even dysinformation. (Consider, for that matter, his titles—e.g., Pathetic Fallacy; Blasted Allegories, Virtues and Vices.) Baldessari might call it an art of “disruption.” More than once during the interview — as he does by way of explaining his “reversals” (of noses, ears, etc.)—he reiterates, “it’s to disrupt your expectations, to get you to look.” And, presumably, to look back and around.

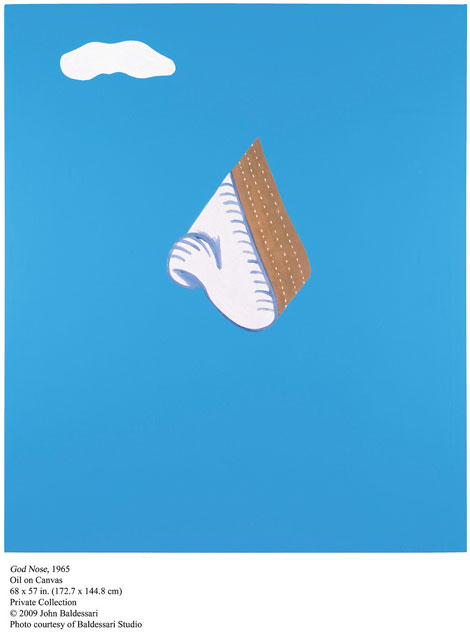

Perhaps it was to be expected that Baldessari and his collaborators would look back for this retrospective, one of his largest to date, but their choice of title amounts not merely to a throw-back, but something of a throw-down. Pure Beauty is the title (and text-image) of a 1968 text painting, which “reads” a bit like Baldessari’s text-painting equivalent to Yves Klein’s empty art gallery—pure (or, in reversal, not at all), entirely abstract, meaningful and meaningless at the same time. “The curator who did the show at the Tate [Jessica Morgan] and I both decided it would be a great title because in the last 10 years or so, the idea of beauty in art has been something that people are talking and writing about; and [we] decided that would be an appropriate title. I’m not positing anything about what beautiful should be.” Nor did Dave Hickey, who has mostly written about what beautiful “does,” though his embrace of the aesthetic is pretty full-blooded. Hickey is often credited as the critic who instigated the most recent round of critical discourse on the issue of beauty and art — though it should be noted that he has also written about Baldessari, in flattering terms.)

Yet, in the same interview, discussing his earliest text and text-and-image conceptual work, Baldessari sums up the kernel of his idea as “just [having] something like that—to read. It’s not supposed to be beautiful; it’s just information. And my idea was why can’t that be art also?”

It goes without saying that apprehending (and responding to) beauty amounts to a kind of information processing. Baldessari is clearly intent upon upending expectations of “beauty” (or its conventional notions), in tweaking, challenging, or even reversing our apprehension—but he is somewhat disingenuous about the formal means he uses to do so. The irony is that there is great formal beauty to be found in much of Baldessari’s work. Regardless of its relative beauty (or rejection of the aesthetic—a matter of taste, in any case), his work as it has evolved over the years has seemed to acquire greater elegance.

It is certainly no less ambitious—as recent shows, including two in Los Angeles at the Margo Leavin Gallery—abundantly evidence. The version of Blue Line (Holbein) he showed recently at Margo Leavin actually drew together installation projects (and art historical references) executed for three different museums, eliciting a diachronic/synchronic tension familiar from much of his earlier work. “The other thing is that if one is an artist, each time one does a work of art, you get more and more acutely aware of your idea of what is beautiful.” Baldessari mused, “So I don’t think one really has to work at it much because you can’t defeat yourself; it’s going to come out anyway. So you have to sort of work against yourself being beautiful because it’ll come out anyway—why work at it?”