If you ever said fine art was a political act, you were wrong. Consciousness-raising—as art’s broad project, as an abstraction somehow implied in the diversions and ironies of what is done in galleries—did not work. Or, as a press release might put it: received discourse about gender, media, normality, The Other, public vs. private, sincerity, truth, capitalism, ownership, sexuality were not questioned, subverted, critiqued or undermined. One hundred years of dissonant and dissident art got us an orange billionaire taking an oath, flanked by blondes, and a homophobe whose smile pinches his appleseed eyes.

Sure Hillary got more votes, but most people either didn’t vote or voted for Trump. The net effect of 100 years of dissonant and dissident fine art has not been a populace that is more aware of anything as a whole than it was before Artist X cut dicks out of magazines or Artist Y watered a tree using only their own tears.

This means some things—and they are things that the art world has consistently refused to take seriously:

• If the most important thing to you is promoting political or social change or even just provoking thought, making fine art is one of the least efficient uses of your time, money and energy.

• Every single one of the thousands of voices selling, promoting, analyzing or making fine art primarily using the idea of its supposed impact or power to provoke thought is selling the purest snake oil.

• Art that has no virtue outside its value as protest has now been proven to have no value, period.

• There are lots of good reasons to make art besides changing peoples’ minds about important issues.

• These reasons can and do coexist in a human brain alongside genuine activist desires.

• The reasons that, despite all this, artworks are constantly presented as conveying some effective cryptophilosophical or cryptoactivist messages have nothing to do with concern about achieving genuine real world goals.

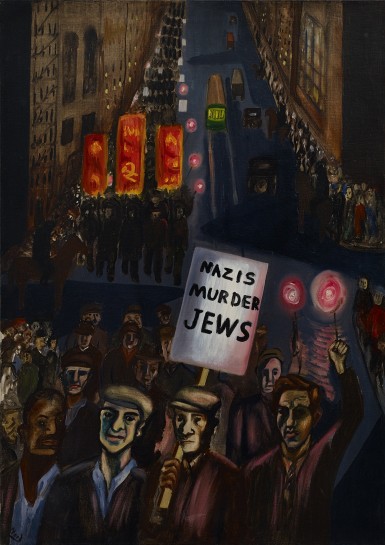

Picasso was wrong: Painting is way better at decorating apartments than as an instrument of war, especially his. Guernica did exactly nothing to prevent the rise of fascism in Spain and the artists and critics who have, ever since, shoved their art out on the battlefield have succeeded more in performing their own intermittently saleable earnestness than in seizing any new ground from the forces that go to war expecting to win.

Like musicians, artists can throw benefits; like actors, artists can occasionally get famous enough to bring issues to an ignorant public; like graphic designers, artists can use their skills to make slogans easier to remember; like teachers, artists can make a difference to the next generation; like the people who own hardware stores and taco trucks, artists can reach out to the communities they are part of. But none of these other professions labor under the illusion that merely showing up and doing the job well must force a change in the status quo—and, more to the point, the graphic designer and the taco vendor aren’t judged by an establishment deluded enough to see itself as a vanguard of a permanent opposition, always shifting, always dangerous, always whetting its cutting edge on the implacable stone of what that guy at that gallery convinced that guy to buy based on what the guy at that magazine said.

It’s said that Trump opposes the NEA on the grounds that he “fears art”—would anyone vote for an art-world naive and narcissistic enough to believe that? While it’s true, dictators have always given artists a hard time, it’s also true that no dictator has been overthrown by a sculpture. Pussy Riot is far more charismatic than Vladimir Putin and has “Pussy” in their name—but somehow Putin is still in charge and they aren’t.

The reasons for Trump’s opposition to the NEA are far less flattering to the superstitions of the culture business: like many Republicans before him, he’s realized if you run an iron over that particular lump in the budget, art people complain, and then you get to show the worst art you can find on TV—and then you win, because most people hate contemporary art.

The myth of disruptive power is based on an emotional reality: I wake up when I want and work at a job that no one believes I have; I don’t have a boss, I don’t get health care, I care about the pictures everyone sees and the words everyone reads in ways they never seem to; I notice things about how the world works that nobody else sees. I make a picture and people see it and they tell me it changed their lives. Faced with a popular culture you have nothing in common with, it’s easy to be lulled into believing that merely by existing you reject everything complacent. But in many ways what drives the artist and art-lover is no different than what drives the fattest fat cat: the desire to avoid what the world keeps in store for normal people.

Soon we’ll see trouble: Americans will be shot by police, drink poisoned water, die unmedicated—we’ll all feel the daily claws, which translate money into time, claw that much harder. Our work will record how we handled the coming desperation; we owe it to all the future’s victims and survivors not to pretend that this is the same as doing anything about it—and we owe it to everything art can be to talk about the real reasons we keep making it anyway.