As of late, queer art exhibitions have been popping up all over America. One such art show is “How Do I Look?: Shifting Representations in Queer Identifications,” which is on display at the Da Vinci Art Alliance in Philadelphia. In this review, I will surface the artwork that I think fall short of reckoning with queer(-ness-), and I will discuss works that can be folded into a productive dialogue on “queer(-ness),” which is still a highly contested term. I will also address that there is no such thing as “queer identity”—one of the ideas that take the power out of queer. This reading obviously comes from my queer theoretical position and ways of understanding the power and productivity of what can (hesitantly) be called “queer art.”

According to the press release, this exhibition explores personal and public perceptions of a queer self, and how it has changed over time. For example, from the criminalization of the sodomite, to the invention of the homosexual, to gay liberation, to the rise of AIDS, to the criminalization of same-sex sex as articulated by the SCOTUS’ Bowers v. Hardwick ruling, to its eventual overturning, to a flurry of other decisions that made homosexuality, or, more broadly, LGBT identities, virtually normal. Thus, as the curators put it, “queer identity” has evolved over time, and they aims to show this.

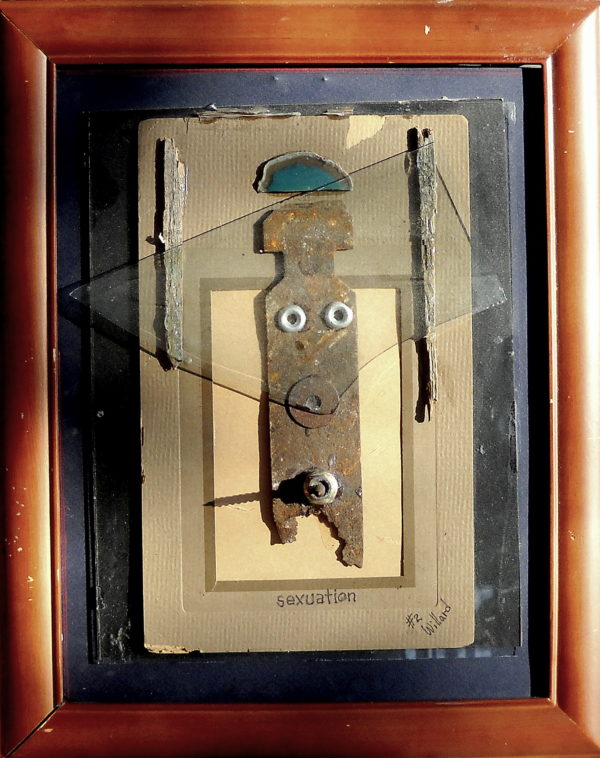

Willard Johnson, 2 Sexuation

“How Do I Look” has a wide variety of aesthetics and subject matter. What connects the art is that all of the work intends to signify queer representations of the self, as the curatorial text and artists’ statements claim. For example, #2 Sexuation by Willard John is an assemblage that connotes a non-binary body—an abstract body—that is both male and female (the idea of “either/or” is discarded). It is made of found objects and can be read as constructing or fashioning the self, otherwise. It has me recall an idea articulated, somewhere, by feminist Elizabeth Grosz: “There are as many genders and sexualities as there are bodies.”

Santiago Galeas, Self Portrait at 25, 2016

Stiofan OCeallaigh, Unselfy, 2016

On the opposite side of the spectrum of “queer” that is “reflected” in the show, is Santiago Galeas’ Self Portrait at 25, in which he has painted his portrait in a rather traditional manner. The only way one would know that this has anything to do with a “queer identity” is that the artist has said so. Galeas’ self-portrait can be compared and contrasted with Stiofan O’Ceallaigh’s Unselfy (2015), in which he has photographed the back of his head while wearing a button down shirt. Thus, he is refusing any traditional notion of self-representation—in fact he flips off tradition and historical norms by his very refusal to present the face: a queer, tactic and/or protest? Indeed, I argue, it is a “queer tactic” that can be seen in the queer (self-) portraiture of artists from Catherine Opie to Gilles Balmet. O’Ceallaigh states: “the Unselfy project is about shame and also ignoring people.” And, tellingly, he also states, “the back of the head is also what you see when you fuck me in my favorite position.” He makes the personal political, as learned by feminists.

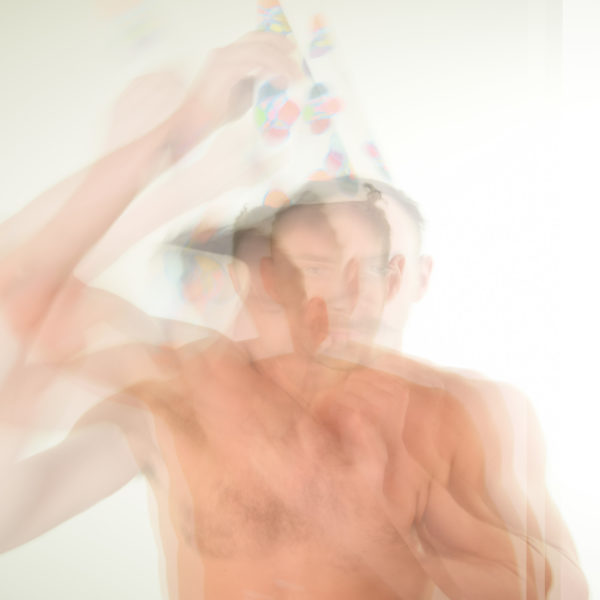

Bennett Shipman, Are You Happy and You Know It, 2016

Also, Unselfy can be tied to other works about the face while simultaneously refusing it. Also, there is a history in queer art (tactics) in art production, that shows a “disfiguring” of the face so that it becomes unrecognizable; for example Bennett Shipman’s Are You Happy and You Know It (2016). In this photographic artwork, Bennett’s self-portrait is blurred. He becomes unrecognizable, and this resonates with O’Ceallaigh’s aforementioned work. Both artists are engaged in a queer history of (self-)portraiture in art: they have inherited certain sensibilities.

Returning to O’Ceallaigh’s Unselfy, and the ideas articulated by the artist, resonates with his Decisions / Decisions piece of 2016. This piece is another (self-)portrait, in which the baby O’Ceallaigh is looking at the camera, mouth agape, and the baby euphoric, but differently pointed arrows are covering his eyes, and across his chest is the word “FAG.” This is a powerful piece about queer youth, or fag youth—for some. And, it has all the power of David Wojnarowicz’s One Day This Boy … of 1990.

Eppchez, Abstract Package no 1 Eye Bulge

I would like to end this review by looking at two artists’ artworks that I think point toward what we can call “queer abstraction” and what, if we can imagine such a thing, the abstractness of queer looks like. The first one is Cat Gunn’s piece, which is an abstract painting titled #1 (n.d.). The lines twist and turn, and even seem to be moving. This recalls what Eve Sedgwick said in Tendencies; she said what queer might mean: “it is a continual moment, movement, motive—recurrent, eddying, troublant.” And this is what this work does in its visuality. The final pieces are by Eppchez, Abstract Package #2: Big Queer Ice Cream and Abstract Packer #1: Eye Bulge of (n.d.)—the abstract soft sculpture connotes the bulges trans men use to highlight cock and balls in pants. Both works reckon with issues of being trans, which raises the question of “queer art” and “trans art”—and how they may complement and trouble each other. Indeed, in ending the review here, I claim there is no “queer identity”—too long an argument to engage in here. But, such art undoes parts of queer (theory) and art, and I want the audience to think about issues of trans, in which queer and “queer art” may be able to be thought differently and otherwise.

“How Do I Look: Shifting Representations of Queer Identities”

Through February 29

Da Vinci Art Alliance, 704 Catharine St., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 19147