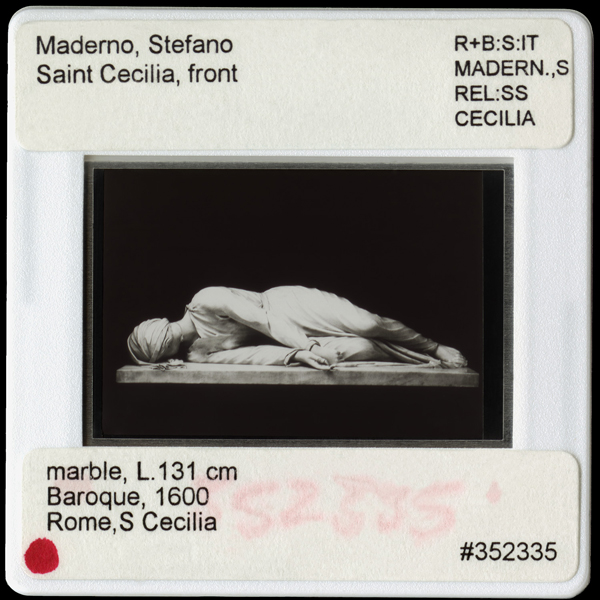

Stefano Maderno’s celebrated sculpture of Santa Cecilia—or rather an enlarged archival pigment print of a slide of the work—greets the viewer on the far gallery wall. Mounted on a substantial support and including information recorded on old-fashioned art history slides, artist’s name, date, medium, style, filing number, as well as a red dot in the lower left, the photograph assumes a kind of sculptural “weight.” At once simple and theatrical, Maderno’s figure lies with her face turned away to reveal three axe wounds on her neck, arms resting in front, head covering falling in gentle folds on the marble surface.

Maderno, Stefano, Saint Cecilia, Front,40” x 40” Archival pigment print, 10 x 8 ft Impression IFR Silver fabric curtain, 2016

Said to be a replica of the martyr’s recumbent, incorrupt body found when her tomb was opened in 1599, the sculpture’s dramatic serpentinata pose won the artist instant fame. Poring through thousands of such slides discarded by art history departments, Vesna Pavlović has assembled an impressive installation that poses intriguing queries not only about obsolescence and our responses to photographic images both individually and communally but also about our perceptions of space and time.

PG TINTORETTO It Removal of the Body of Saint Mark, 1562-6630” x 30” Endura metallic color print with metal stand, 2016

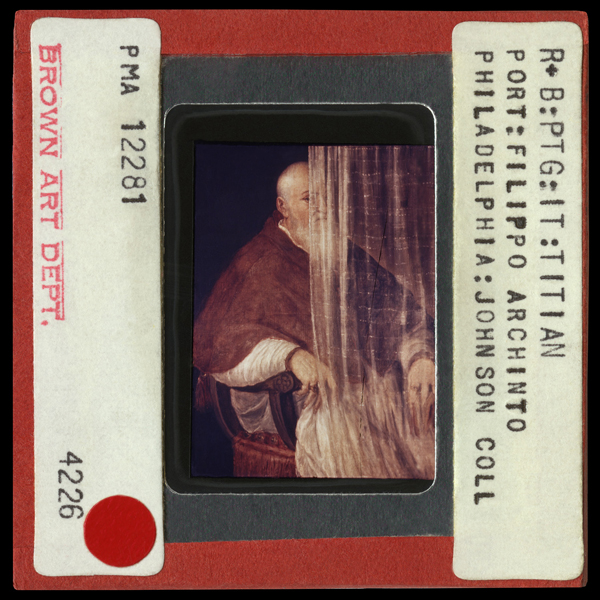

A common feature of the images Pavlović has chosen is the inclusion of draped fabric: among a score of slides, Tintoretto’s Removal of the Body of St. Mark; Alma-Tadema”s Midday Slumbers; Tiepolo’s Time Unveiling Truth, and the three goddesses from the east pediment of the Parthenon. (Interestingly this latter slide is reversed, perhaps a nod to the “oops” factor in loading the carousel.) But one of most arresting images is Titian’s portrait of Filippo Archinto. The Archbishop sits in the familiar three-quarter pose often used for churchmen, with a translucent curtain veiling just over half his figure, this unwonted motif perhaps symbolic of the ecclesiastical machinations that precluded accession to his appointed office.

R+B:PTG:IT:TITIANPORT:FILIPPO ARCHINTO, 30” x 30”Endura metallic color print with metal stand, 2016

Underscoring the atmosphere of former art history classes, a projector in the second room flashes images against a veiled screen: Bosch, Vermeer, Manet, and on and on, the sound of slides dropping in a rhythmical pattern, echoing the word “fall” of the show’s title. Particularly meaningful, this display translates each two-dimensional image—itself a narrative implying sequence, hence time—into a spatial construct. And the overall installation alludes to the space time-continuum on an even deeper level. Confronted with superannuated technology, the viewer “sees” the past as “scenes”—spatial time, if you will.

TITIAN (It) Examples of Techniques in Venetian Painting, 40” x 40”Archival pigment print, 2016

Significant also is Pavlović’s focus on fabric: each slide features draped cloth of some sort, the screen is covered by poly-silk fabric, and a translucent curtain covers a large window in the second room. Not only do these materials reflect the slides, which were sometimes called “transparencies,” but they also suggest the rich symbolism of the veil. Among its many associations, the veil figures in Renaissance allegory when truth is “unveiled,” as in the installation’s reproduction of the Tiepolo painting. Is the artist implying that art and more universally, space, time and even reality itself is “veiled” to our understanding?

Vesna Pavlović: “Fall and Folds”

Whitespace Gallery

Atlanta GA

June 24-July 30, 2016