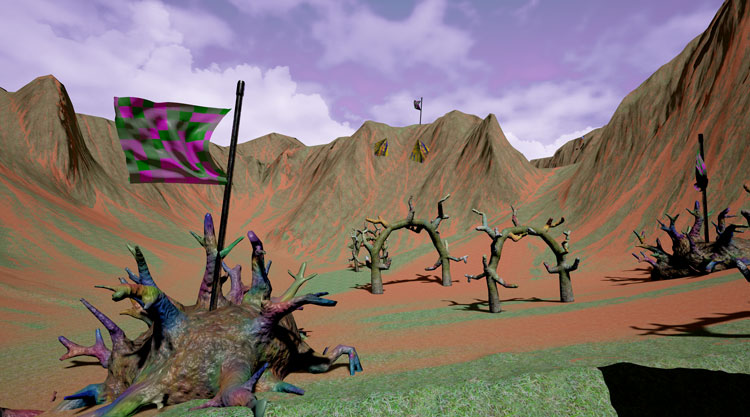

Jeremy Couillard says that the pleasure of working with virtual reality (VR) is that he can move away from “a deceitful world I deeply wish did not exist. I need to create an alternative to that universe so I don’t go insane.” A video and installation artist, and teacher at LaGuardia Community College, Couillard had a recent exhibition at the Louis B. James Gallery in New York. Visitors entered “Out of Body Experience Clinic” to find what resembled a doctor’s waiting room: coffeemaker, TV, old magazines, utilitarian furniture. Donning a nearby Oculus Rift headset, visitors then found themselves in a virtual clinic similar to the one they had just been inhabiting. Then suddenly, as if called back to Heaven, they perceived themselves floating up into the air before possessing a CGI-character of Couillard’s creation. The remaining 8-minute simulation—something between video art, video game and LSD trip—depends on the viewer: floating through pastel deserts and rivers, dining with giants, exploring a whale’s innards.

“When I make something like a VR experience,” Couillard explained in an email, “it’s somewhat about anxiety, spirituality, consciousness; but also it’s about new media. To some extent, it’s about generating a space for an absurd alternative use of technology.”

This future-technology had first been used by photographers for more realistic endeavors: 360o video allowed photographers to capture surround-sight images—in “Welcome To Aleppo,” available on YouTube, viewers can click and pan their mouse through the bombed-out streets of the Syrian town. And using the Phantom Camera, which shoots at 720 frames per second, photojournalist Christopher Morris revealed the American political landscape in a new, haunting, slowed-down way. But recently, Google, as if predicting Couillard’s quote, used new media to generate a space for the absurd by generating the absurd: Deep Dream.

Starry Night, Google Deep Dream

To understand the way Deep Dream works, consider that when looking at an electrical outlet many people will see it as a surprised face. Now imagine if instead of looking at an outlet, you scanned your entire visual field, finding faces wherever you could—rocks, trees, sky. Deep Dream’s “neural network” algorithm, meant to approximate the human brain, does something similar. Fed an image, Deep Dream tries to make sense of what it is “seeing” by finding patterns that remind it of photographs it already “knows.” With the abundance of animals on the Internet, Deep Dream often turns an image—as it did with van Gogh’s Starry Night—into a trippy mix of bird eyes, inflated fish and tumescent dogs.

“I don’t like Google Deep Dream, too cheesy,” says conceptual artist George Legrady. Theorizing on and using digital photography in his art since its inception, Legrady is now a professor of interactive media at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and holds a joint appointment in the school’s Media Arts and Technology (MAT) graduate program and its Department of Art. He also directs UCSB’s Experimental Visualization Lab, where his latest work is “Swarm Vision.”

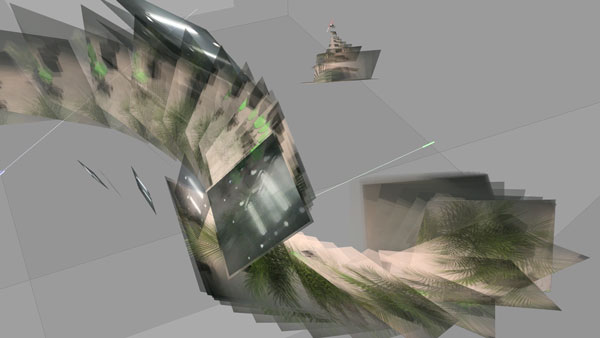

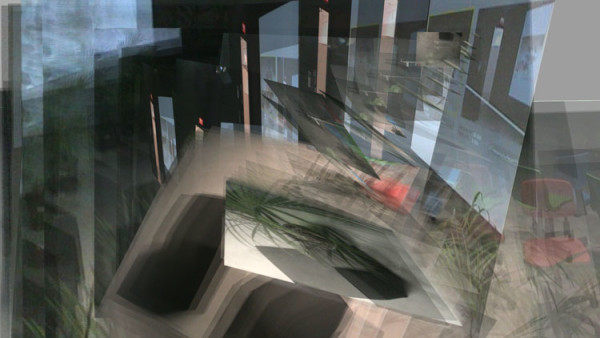

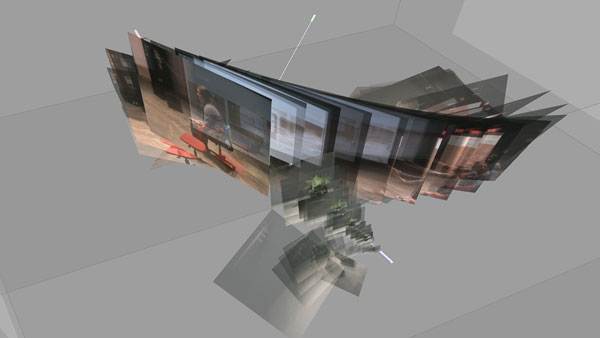

George Legrady’s “Swarm Vision.”

Like Deep Dream, the project is about “machine learning,” Legrady said via email. With “Swarm Vision,” Legrady and his team are trying to teach a computer, and camera, to look around and “capture images the way a human would.” Installed in a gallery space, three autonomous cameras travel along rails, panning and tilting and zooming as they search the room for interesting photographs based on human rules of photography; concurrently, each camera is alerting the other two cameras to their findings. (Imagine three photographers—each with a different artistic approach to composition—snapping pictures, and making recommendations to one another.) “Swarm Vision” photographs are then projected on a screen for humans to admire.

George Legrady’s “Swarm Vision.”

While this may seem a departure from Legrady’s earliest work, he regards “Swarm Vision” as part of his gradual software update: “We each belong to an era—and my training was in the mid-1970s, in the days of conceptual art—when systems, processes, modeling and analysis were [all] part of the expressive component of the art-making process.” Art created with future-tech often has viewers more focused on “How did they do that?” rather than “How does this make me feel?” Legrady both embraces and denies this schism. “I usually look for the concept, what issues are being addressed. Then the impact of the installation with its technical processes are something to examine, and meanwhile I am also looking for aesthetic coherence, and poetic resonance.”

George Legrady’s “Swarm Vision.”

As Couillard’s and Legrady’s work indicates, the current state of photography often seems to be an intertwining of various art media with just as many STEM-subject media. “It is both an art and engineering project,” Legrady says of “Swarm Vision.” “I show it in both contexts. The art begins with the initial concept and overall aesthetic decisions—it’s not unlike directing a film, where you have specialists who contribute their expertise in combination, and in response to, the conversations with the director.”

Still, Legrady says that even with the use of new commercial technology, or artist’s creations of even newer technologies, those working in the field are just doing what art-photographers have done since the first camera appeared: “Photography,” he says, “has always been a technological machine.”

Editor’s Note: Congratulations to George Legrady, recently named a 2016 Guggenheim Fellowship recipient.