One of Los Angeles–based artist Audrey Wollen’s Instagram posts features an undated 1890s painting in which a nude woman reclines, examining herself in a mirror she is holding up to her face. Red beads are wrapped around the woman’s neck and ankle, bringing to mind Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber (“A choker of rubies, two inches wide, like an extraordinarily precious slit throat.”). Wollen has captioned the photo: “if u look at paintings of girls and replace each mirror w/an iPhone in yr head, u will realize that nothing has ever been different.”

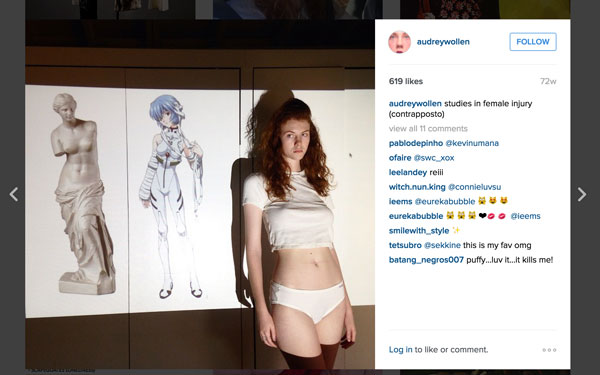

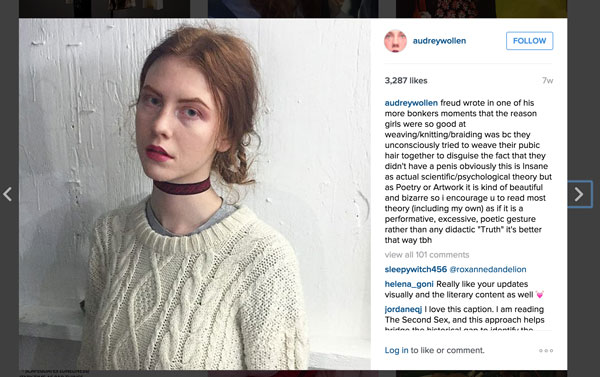

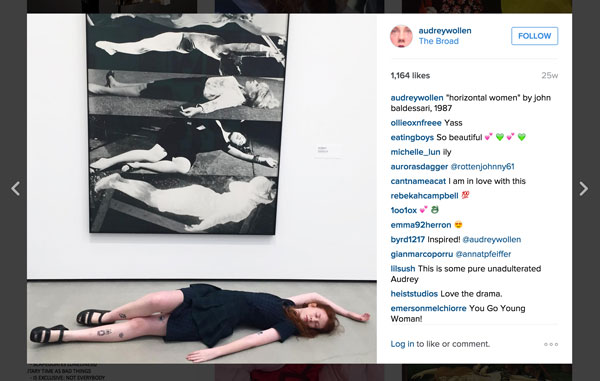

With her Instagram-based work, 24-year-old, CalArts-educated Wollen seems to have set out to prove just this. She uses her phone to objectify herself, to document her pain, her tears and her hospital visits. Most of all, Wollen fosters a critical dialogue on feminism, art history, representation and performativity of femininity, sadness—and how the expression of that sadness is an inherent threat to the status quo of oppression. She does so specifically through challenging the hyper-positive, self-love-or-nothing feminism that permeates the Internet, and alienates feminists who are unable to subscribe to it.

“Working hard, staying positive, fighting back, keeping strong: this isn’t my language,” Wollen tells me in an email interview. “I think it’s time to reassess our ideas of protest so that all the available languages can be heard in feminism… Our bodies and our pain, physical and emotional, have to be taken back, and I don’t think it can be done by romanticizing the inverse of our symptoms: strength, energy, vigor, sanity, “health” as defined by masculine standards. Our symptoms can be transformed into our weapons, and create a new image of what strength can look like.”

She has coined a term for this idea: the Sad Girl Theory, which says that the expression of female sadness ought to be viewed as an act of political protest and resistance rather than personal failure. Wollen lives out the Sad Girl Theory in a big way: the most compelling images in her project are often those in which she documents her own medical experience, photographing herself in hospital gowns or coquettish outfits at a pain management center and the hospital. “Taking selfies in hospital rooms opens up a small bubble of autonomy in a world where I am objectified the most. There, I am undressed in front of strangers who prod and measure, calculate my risks and rates of life, cut me open or sew me closed, and it’s hard not to feel like a rag doll or a mannequin. I have to go to the doctor a lot for a chronic disability—at least once a month, and that in itself is an endurance performance piece, but to go and document my body over and over again reminds me that I am still a person, capable of my own performative gestures and my own artistic practice.” In a post, a follower asks Wollen why she is “always at the Dr.” Wollen never says; nor did she for this article. But in another post, she reveals: “as some of u may know… I was diagnosed with cancer at 14” for which she is routinely monitored for recurrence.

Wollen is incredibly sensitive to the patriarchal nature of the medical system. Her hospital photographs remind me of the phenomenon of “hysteria” in 1800s France, a since-debunked disease applied exclusively to women based on vague “symptoms” ranging from sexual desire to anorexia to seizures. I think of Augustine Gleizes, whose “hysteria” was documented at Salpêtrière hospital. There, the focus under doctor Jean-Martin Charcot was not on a cure but on managing the “disease” and recording what it looked like. Augustine and other women were used in staged re-enactments of their symptoms, both in public lectures and through photographic documentation. These women, while surely experiencing real illnesses, were also celebrities to a public fascinated with hysteria. By participating in this hospital culture of performing their illnesses, the patients were able to articulate their very real distress. When comparing Augustine’s medical performances to Wollen’s, there are uncanny similarities. Both are constructed through the gaze of others; many of Wollen’s are taken of her, not by her as she poses on medical examining tables.

Wollen is quick to confirm that Gleizes is one of her Sad Girl muses, as well as St. Catherine of Siena, Alice James, Zelda Fitzgerald, and many other women whose suffering was difficult to medically classify. “I think the history of girls’ sadness, as something that has been eroticized, glamorized, sedated, dismissed, and caught in the medical gaze, is essential to understanding how we can utilize it now for our own political purposes,” she explains. “We’d like to think that all that nonsense ended in the early 20 th century, when we debunked “hysteria” as a legitimate disease, but it’s still going on. There are plenty of chronic conditions that are unofficially considered ‘women’s’ diseases, and plenty of women who are manipulated into silence by a patriarchal medical system. I don’t know if all that much has changed, it just goes by a different language now.”

Much like the general conversations surrounding social media–based art projects, performing one’s illness and suffering makes it convenient to raise questions of authenticity. But Wollen says, “I don’t care about seeming authentic. Like, at all. This idea of the authentic as this inherently good, measurable, static thing that you can either be or not be—it’s a truly bizarre and horribly oppressive ideal… It leaves no room for uncertainty, plurality, wobbly ideas or personhoods.”

Wollen’s work largely functions as seizing and manipulating the male gaze that she is inherently subjected to. (“I wish I could just be a person, and not a walking photograph of a naked girl. But I wasn’t given a choice. I was being treated as if I was only a photograph of a naked girl long before I started taking photographs of myself naked,” she once said in a VICE interview.) But the question of whether or not these manipulations are productive is a valid one.

Rosza Zita Farkas writes in Temporary Art Review: “There are hierarchies that are afforded to certain (female) bodies, degrees of agency in one’s self-representation, perhaps at the expense of the visibility of others. The act of reclaiming agency over one’s body—of having control over its image—is not only a well-trodden ground, but also exists in a society where that act (both in art and in general culture) has not demolished the gaze. The body needs to do more than simply present itself; it needs to insert itself… the image does not exist alone… “

That being said, I argue that Wollen’s work does seem to insert itself quite forcefully into a historical conversation of capitalism and the patriarchal oppression of women. Wollen says she chose Instagram as her platform deliberately, which makes sense, given that her topics of dialogue (girls, bodies, objectifications, and performance) literally constitute what Instagram is. It also provides a platform by which she is better able to reach other Sad Girls than through traditional media. “I realized that I may be giving my content to some tech company’s insidious empire,” she says, “but I’m also having a conversation about Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick with a 14-year-old girl in Kansas, and she’s teaching me about her experience of girlhood. That’s so precious, and that’s an okay trade-off for me.”

In Wollen’s project, it seems that the body’s representation and the terms of its reproduction are intertwined, and with just cause. Her manipulation of her representation seems to be taking tangible steps toward redirecting the male gaze, though it might not yet be clear toward what.

I’m quite curious to watch what Audrey Wollen will do with her newfound platform. Instagram makes her work accessible to a large number of women, but it is also easy to see her as an artist in conversation with Frida Kahlo, whose art communicates both her physical frailty and emotional strength, or Cindy Sherman, whose concept photographs required her to fill many roles—photographer, model, author, director, etc. At the very least, her use of self-documentation and fearless expression of her own pain and suffering serve to create the fuller dialogue on feminism that the Internet so desperately needs.

All Instagram images courtesy Audrey Wollen.

Catch Audrey Wollen at an Artillery sponsored panel discussion Saturday, May 7, at LACE in Hollywood. For more info visit our facebook page.