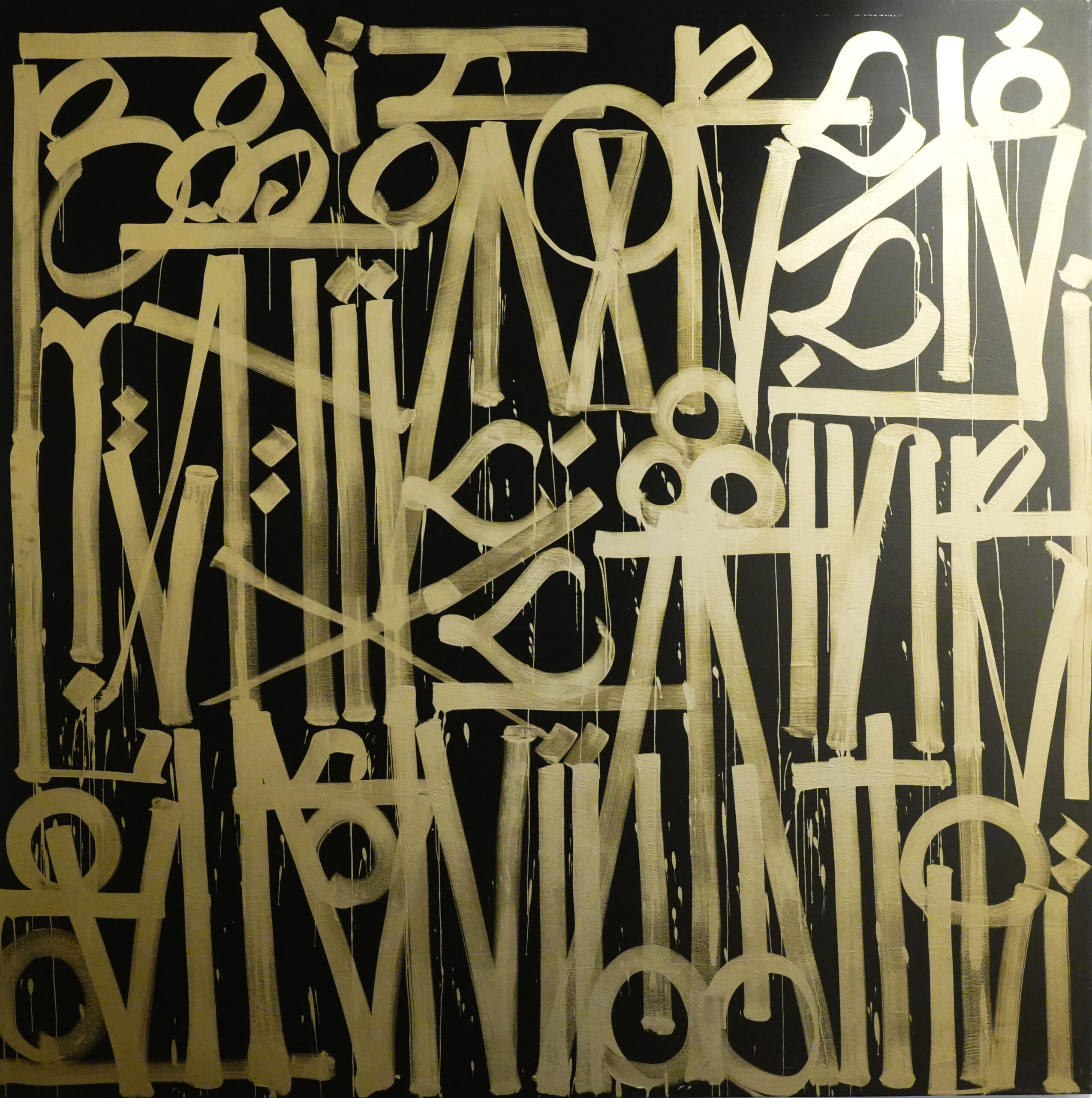

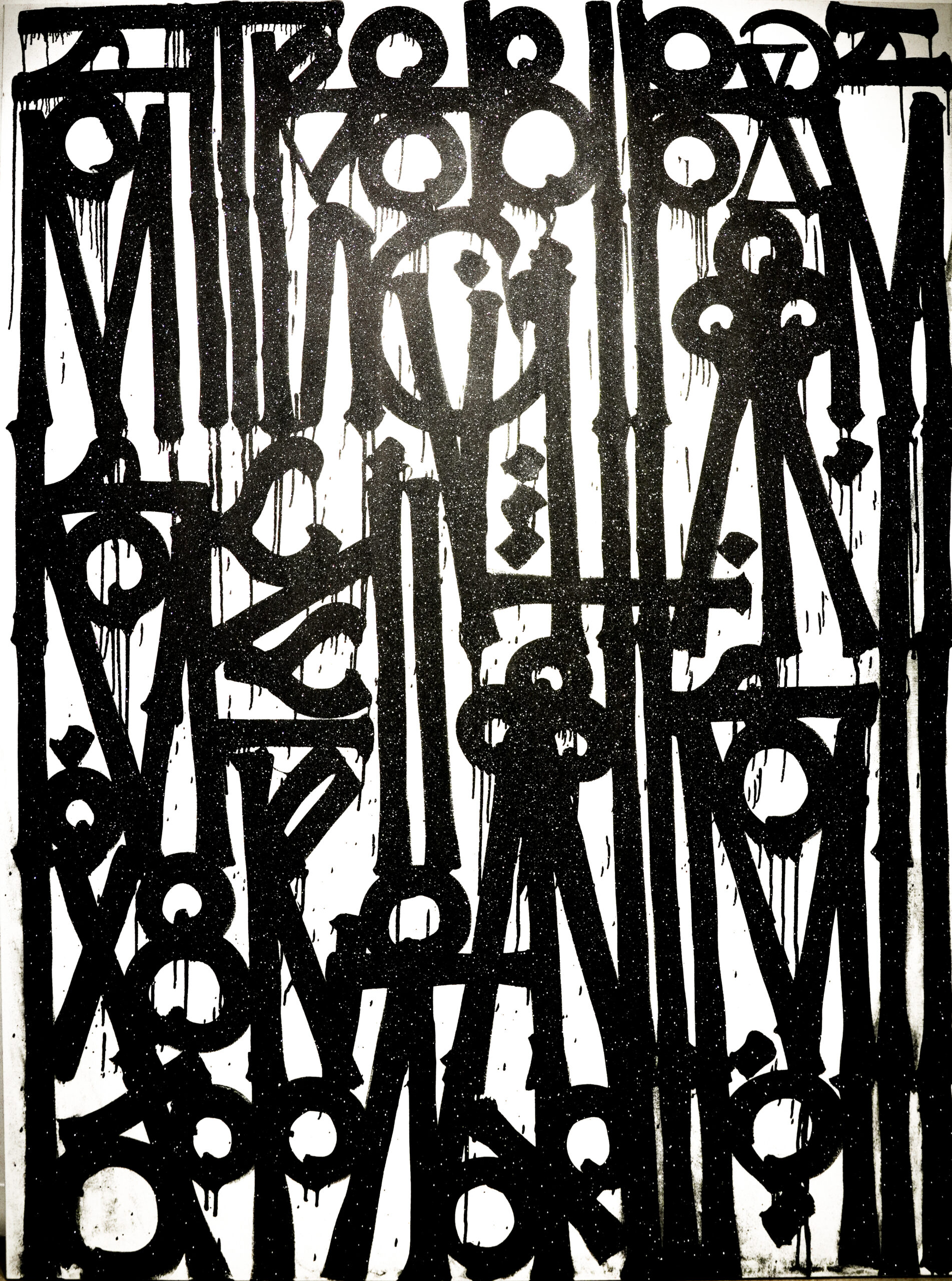

The glittering paintings wouldn’t be out of place in Giza or Athens or Persepolis. RETNA’s bold scripts are the kind that shout down at you from the tops of ancient monuments. Sometimes elements of the painted characters resemble ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, sometimes Arabic calligraphy, sometimes a more European-looking, Knights Templar-esque code of crosses and keys. The texts of RETNA’s recent solo exhibition in London are an indecipherable international amalgam. In JD Malat Gallery, we’re Indiana Jones discovering the mysteries of an unknown ancient civilization. It’s abstract art in denial: calligraphy that teases us with the possibility of textual meaning, but ultimately forces us to resign to awe-inspiring illegibility.

Playing with the exhibition’s title, “Locked Lines,” the press release attempts to frame the “stillness” of RETNA’s scripts as an antidote to the frenzy of London’s concurrent Frieze fair—paintings that make us slow down (there’s a not-so-nimble pun on “freeze”). Certainly, it’s refreshing not to be harping on about dynamism in painting again, but (call me old-fashioned) surely a static form can’t be that highly commended for being static? Really, RETNA’s achievement lies not in slowness, but in solidity and grandeur. The gallery describes the canvases as monumental, but by today’s standards they’re not really that big. What’s monumental is the cryptic, densely packed, ancient-feeling script, which allows some of the show’s highlights—like Soldiers of the Woods (2025) and Gold Standard Classics (2025)—to evoke a temple’s grand façade. By contrast, Crosses and Arrows (2025), the show’s weakest work, misses the mark: much less lettering and much more blank space leave it feeling frail and deflated. Paint is naturally static; it’s not naturally monumental. It’s particularly special coming from an artist with a graffiti background, a form better known for speed and impermanence than for evoking ancient monumental inscriptions.

Yet small dribbles of paint from even the most mysterious, regal characters reveal that they’re still, ultimately, graffiti. We’re forced to see that it’s just paint—don’t get too highfalutin about epigraphy. RETNA doesn’t forget his early days in the ’90s LA street art scene as a self-taught teenage graffiti artist, and then as part of The Seventh Letter crew (the ambitious LA collective whose name invokes the letter G for “Gods of Graffiti”). Sometimes graffiti’s rebellious spirit breaks through into RETNA’s paintings more obviously. Sometimes they drip excessively as if a storm is washing them away, as in Silver Star (2025). Sometimes the rigid horizontal structure is broken, and jumbled characters tilt to one side as if after a landslide (see Eisner, 2025). Sometimes the predominant colour schemes, Zen black-on-white or sombre black-on-black, are exchanged for the glitzy blues, purples and golds of glamorous pool parties (Kaleidoscope, 2025). RETNA may owe his entry into the artworld as a solo graffiti artist to the characteristic large-scale murals of his early shows (particularly those supported by LA’s MOCA, the 2011 group show “Art in the Streets,” and the 2013 solo show “Para Mi Gente”). But shrinking this style to a smaller scale gives RETNA more opportunities for agility, experimentation and play.

Because then there’s the sparkle. Skimming over the “diamond dust” material on wall labels (thinking it’s probably just a catchy name), it’s easy not to think much about the glitteriness at first, beyond the visual effect: the contrast between depthless matte backgrounds and characters glittering outwards (which photos can’t seem to capture) can be visually unsettling, sometimes making it difficult to focus your eyes. An optical illusion, another form of indecipherability. But it’s not merely glitter. After re-reading the wall labels, I had to double-check with a gallery assistant, who seemed exasperated that people keep calling it that: the glitter is real diamond dust; the gold paint is real liquid gold. (After overcoming disbelief, the natural instinct is a worried look at the stoppered-open gallery door, now a heist’s likely entry point.) There’s an echo of For the Love of God (2007), Damien Hirst’s diamond-encrusted skull sculpture. The glittery and the regal together point to the glitz and glamour world of fashion and celebrity, ruled by the sparkling modern-day monarchs of pop culture: the rappers, the pop stars, the supermodels. It’s Andy Warhol’s wealth—and fame-driven art of American consumer culture and mass media, but with a 21st-century Pop Art re-orientation: from mass production to exclusivity. RETNA’s regal texts are meant to be understood by someone, but not us.

RETNA. Soldiers of the Woods, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and JD Malat Gallery.

This is no longer ordinary graffiti: it’s the millionaire graffiti of the glitterati. Sometimes the exhibition reminds me of the semi-abstract text-based paintings of Glenn Ligon. For example, RETNA’s glistening black-on-black paintings, Night Owl (2025) and Ancient Script (2025), echo the illegible text of Ligon’s Mirror #9 (2006), only Ligon’s black surface glistens with coal dust. Ligon’s texts, where legible, are in English, and Ligon gives us clues: often they’re extracts of race-related writing, such as the novels of Gertrude Stein or the essays of James Baldwin. RETNA takes abstraction further, making texts impenetrable. The multilingual mixture becomes something even more global–international even beyond the influence of his African-American, Salvadorian, Spanish and Cherokee heritage, international even beyond the visibility of his graffiti projects from LA to New York to Dubai to Hong Kong. It’s the glittery global language of wealth. If Ligon’s illegibility asks questions about the visibility of Black voices in history and literature, RETNA’s illegibility asks questions about 21st-century pop culture and celebrity.

There are parallels with another LA artist, Lauren Halsey, who also works with monumentality and graffiti, though primarily in sculpture. While RETNA gestures towards hieroglyphs and ancient times, Halsey is more direct: her work for the Met’s Roof Garden Commission, the eastside of south central los angeles hieroglyph prototype architecture (I) (2023), is a modern-day Angeleno-Egyptian temple modeled on the 1st century BC Temple of Dendur in the museum below. Instead of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Halsey’s temple walls display carvings of modern graffiti and of posters, all inspired by her South Central home (“My Hood Gucci,” “The Braid Shack,” “BLACK WORKERS RISING FOR JOBS, JUSTICE AND DIGNITY.”) While Halsey’s monumentality is about community and access, RETNA’s monumentality is about limitation. It’s more like the Behistun inscription, a monumental ancient Persian work carved so high up a cliff face that it’s impossible for humans to read—for the gods’ eyes only.

And while Halsey moves from transient to permanent, carving graffiti and posters in stone, RETNA moves from permanent to transient, putting regal inscriptions in paint. RETNA’s mixing of “low” and “high” artforms in a prestigious contemporary art context in some ways ennobles modern graffiti: a fragile art (easily painted over, dependent on other structures), an art of the fringes and of rebellion, is bestowed with something of a centuries-old temple’s reverence. An empowered graffiti, not illegal, but legitimate; not of poverty, but of decadence. However, at the same time this implies some degradation of ancient inscriptions. Ice Cream (2025), whose white characters sparkle on a matte neon pink surface, resembles a glistening Barbie-esque candy cane. Simplicity in Red (2025), with a script of clichéd romantic red sparkles, is like a king’s overblown Valentine’s day card. They’re both almost too sickly sweet. This is RETNA’s playfulness, perched at the centre of a delicate power dynamic: simultaneously building monuments and undermining them, both ruler and revolutionary.

The paintings’ regal dignity clashes with what stuffier, snobbier viewers might deem their glittery “bling”—that word on the wealth-drenched frontlines of the war between old and new money, which counts the artworld among its best battlegrounds. When does glitter become gauche? When does taste become tacky? Some would say that it’s abstract art livened up, others pimped up. Some would say that it’s graffiti elevated, others corrupted–gentrified for artworld consumption. RETNA captures conflicts at the heart of the artworld and its growing pool of participants. It’s particularly poignant as the work of an artist with a significant commercial presence—an artist who’s worked with luxury brands Chanel and Louis Vuitton, who’s produced album art for Justin Bieber (for the 2015 album Purpose). So there’s relevance to Frieze, and the artworld glitterati, after all: indecipherable, monumental, glittery graffiti that’s less about legibility than about glitteracy.

I leave wondering if I’ll see graffiti differently now. But there won’t be any in this part of London—perhaps the scars of a Banksy that’s been fenced off, chiseled away and sold. Outside the gallery, between the Mayfair buildings, a tricycle-taxi pumping out trap music squares up with a Lamborghini. This is RETNA’s neighbourhood now.