Entrusted to the sprawling Skirball Cultural Center in Brentwood by New York’s Jewish Museum, “Draw Them In, Paint Them Out” presents a handful of Philip Guston’s depictions of cowled Ku Klux Klan figures, alongside Trenton Doyle Hancock’s ambitious, mixed media “responses” to his precursor’s work. The exhibition may succeed in drawing viewers in, despite the remote location of its second venue. During my visit, staff were huddled together at the show’s entrance, where they debated the pitfalls and merits of displaying Guston’s and Hancock’s representations of Klansmen.

At a glance, this pairing might seem unbalanced. Hancock is squarely in the middle of his career, whereas Guston is a titanic figure in the history of 20th-century painting, whose multipartite oeuvre has been laid out before us with meticulous annotations. Nonetheless, “Draw Them In…” allows us to contrast Hancock’s appropriations of Guston’s Klan imagery with their source material, and to assess both artists’ complex responses to racism and antisemitism. Hancock (b. 1974) is a Black artist who was raised in Paris, Texas, a city with a large Black minority where racial discrimination and violence are endemic. His immersive video installation, titled Paris, Texas, Fairgrounds (2024), addresses the high-profile lynching of Henry Smith in 1893—an event that Hancock’s maternal grandmother actually witnessed. Guston (b. 1913 – d. 1980) was the child of Jewish immigrants who fled pogroms in Odessa and eventually settled in Southern California. As an artist emerging on a national stage in the lead-up to World War II, he took pains to safeguard his ethnic identity, famously changing his name from Goldstein to Guston.

The quantity of Guston artworks in “Draw Them In…” is disappointingly sparse, despite buy-in from Musa Mayer, the artist’s daughter, and the President of the Guston Foundation. The exhibition commences with Guston’s politically conscious, WPA-era murals. Because all are location-specific, and a few have been destroyed, the murals are shown only as tepid reproductions pasted on flesh-pink walls. Even so, I’m awed by Guston’s ability—as a 23-year-old painting far from home in Morelia, Mexico—to juggle multiple vanishing points at epic scale, and convincingly render muscle, fabric, and stone in The Struggle Against Terrorism (1935). I find his early reflections on violent extremism to be earnest and affecting. Others did, too. In 1933, members of the American Legion, the KKK, and the LAPD’s “Red Squad” disfigured Guston’s first public commission—a mural for the Marxist John Reed Club that depicted a Klansman whipping a defenseless Black victim.

Also on view are Guston’s infamous late drawings and paintings, rendered in a unique graphic style that roiled the New York art world when he debuted them at Marlborough Gallery in 1970. Painted wet-on-wet with inky Mars black, cobalt blue, titanium white, and cadmium red, Guston’s outlandish and unfussy figurative repertoire came to include (in addition to Klansmen) disembodied appendages, hobnailed shoes, naked lightbulbs, clocks, and trashcan lids— motifs that reference his personal history as well as his earliest paintings. Although Guston’s newfangled style sustained his own profound introspection, it effectively led to his exile from the pantheon of Abstract Expressionism, less than a decade after a bountiful and widely celebrated retrospective of his color field paintings at the Guggenheim Museum in 1962.

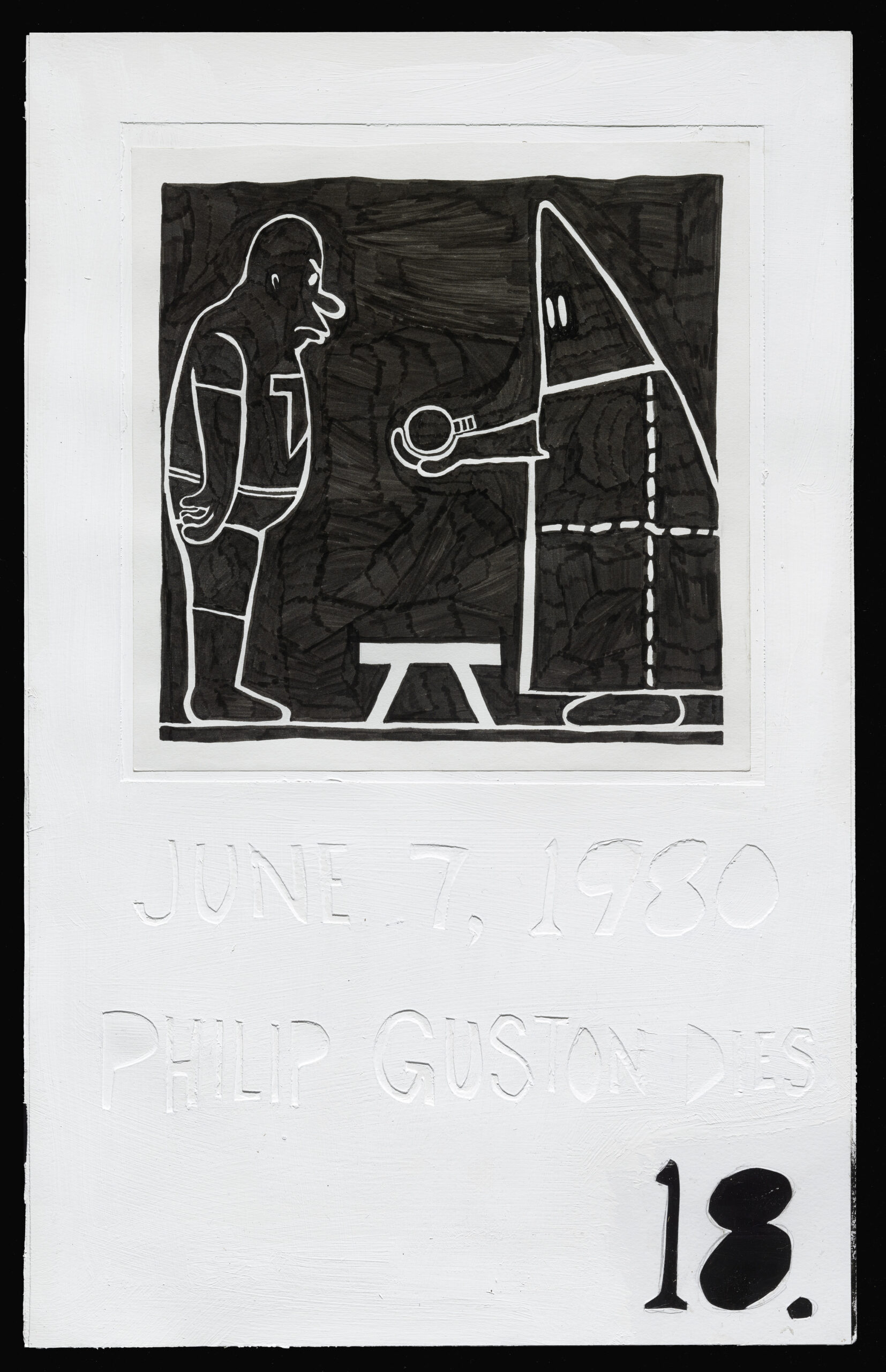

Much of Hancock’s work in “Draw Them In…” appears to follow from Epidemic! Presents: Step and Screw! (2014), a sequence of 30 graphic drawings that stage a perilous confrontation between “Torpedoboy,” Hancock’s shapeshifting alter-ego, and a roomful of Guston’s Klansmen. Dated descriptions of both real and fictional events are crudely incised beneath each Step and Screw! panel. Like comic-strip captions, they recount significant milestones in Guston’s and Hancock’s lives, punctuated by a poetic array of fragments from other “narratives”—such as the 1922 test flight of an early helicopter prototype, or the debut of Wim Wenders’s film, Paris, Texas, in 1984. Correspondences between these records are plainly random, but their juxtaposition prompts viewers to construct links between them.

Hancock has said that his medium “is plastic,” a reference to the acrylic paint and petroleum-based found materials (namely, bottle caps) that he uses to create large, tessellating grounds populated by cartoonish figures from his own evolving theogony. For the past decade, Hancock has continued to rework the hieroglyphic ‘architecture’ of the Step and Screw! standoff in large-scale paintings. Several on view at the Skirball portray a Guston-style Klansman presenting a symbolic object to a leery, tighty-whity-clad Torpedoboy. In a 2020 composition, the Klansman proffers a “Star of Code Switching,” while text incised in the surface of its hood like a speech bubble reads: Take it. It will help you live longer. The Klansmen’s trinkets seem to promise only qualified forms of socioeconomic security and mobility. In accepting any of them, Torpedoboy would ascend to a system that privileges one group at the expense of others. Most recently, in TTT vs KKK, When I Think of Home (2024), Hancock remodels his avatar as a muscly, three-headed linebacker who looks poised to unmask a particularly ghoulish Klansman, or to crush his capped head between his thumb and forefinger. This picture supplies catharsis, but it lacks the polyvalent open-endedness of Hancock’s first Step and Screw! project.

At the Skirball, the wall texts posit that Guston’s paintings of Klansmen are pure satire: they cut white supremacists down to size by depicting them as ‘deflated’ buffoons. Hancock himself advanced this explanation in a talk organized by the Jewish Museum to inaugurate the exhibition. Performing a close reading of Guston’s Riding Around (1969), the younger artist observed that the Klan is “going nowhere fast;” the tires of their jalopy are flat, and the perimeter of the canvas hems its occupants in. Yet an irrefutable undercurrent of identification runs between Guston and his Klansmen. They enjoy smoking, painting, looking, and thinking, just as he did. During a 1978 conference titled Art/Not Art at the University of Minnesota, Guston declared that his Klan paintings were ‘self-portraits.’ “I perceive myself as being beneath the hood,” he told his audience. “The idea of evil fascinated me, and rather like Isaac Babel, who had joined the Cossacks, lived with them, and written stories about them, I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan.”

To my eyes, Guston’s Klansmen look ignorant of their identities. They glide along in heedless flocks or stare unblinking at one another with tall, rectangular eyes, evincing a total lack of comprehension. That is to say, they are wicked and injurious without realizing it. In a small, charcoal drawing from 1969 (the year in which his comical Klan pictures first emerged), Guston outlines a stout trio of hoods slugging batons wildly in all directions. The image summarizes the banal evil that the artist was attuned to in his late years. With just a few lines, he reveals a human predilection for hatred and violence, latent in any of us (indeed, in artists, too) that precedes a tangible target, though it strives constantly to find one.

Hancock has chewed self-recognition over as well, particularly in a spate of greyscale compositions he created between 2021 and 2023. In Globetrotters (2023), a grid of silhouettes picture Torpedoboy lurching through affects (confidence, happiness, shock, complaisance), before transforming into a Klansman. Another work, titled The Boys in the Hood Are Always Hard (2023), shows Torpedoboy receiving some reach-around stimulation from a Klansman while seated on its lap. The sex act is symbolized by a bare, illuminated lightbulb—one of Guston’s calling cards. Besides its tortured allusion to the film Ghost (1990), Hancock’s painting contains another haunted act of doubling: with their left hands joined together, the unlikely couple traces a triptych of drawings that portray Torpedoboy executing the Klansman with a sword. I like to imagine Guston looking at this image. He would have taken pleasure in its tangled Punch and Judy show.