“It Smells Like Girl,” at Jeffrey Deitch, in conjunction with Company Gallery, shares its title with a Tala Madani painting depicting a suspiciously phallic object, a lone actor against a cloudless blue sky. Stark and funny, the phallus is the main character, but its melodrama gives it a pathetic quality. The title is borrowed from the Hole song “She Walks on Me.” Madani’s painting is the sole instance of a work directly indicting men; the rest of the show is chock-full of both the female figure and that with which she adorns herself; the majority of the work revels in self-directed displays of feminine psychosis. Largely a romp through an arguably stacked lineup that favors the punchy and arresting, “It Smells Like Girl” is vast and comprised of 53 works, all by women artists. The show is centered on the concept of “female hysteria,” and the press release details rather loosely and abstractly the designation of the female hysteric, embracing hysteria as a necessary reaction to the constraints and double binds of femininity.

The hysterical woman is culturally well-documented. She is a played-out trope in accusation and reclamation alike. Almost bygone at this point, the hysterical woman is water under the proverbial “granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn” bridge. And the show’s title? Fishy at best. By no means does “It Smells Like Girl” take hysteria as a diagnosis seriously. But what if, for our purposes, we do? In the late 1890s, Freud, along with a colleague, Josef Breuer, developed theories of the hysteric in Studies in Hysteria, and it is through this lens that I find substance for analyzing the relationship between the body, language, and art object.

Meriem Bennani, Defaya Nefsya, 2023. Photo: Paul Salveson. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, New York.

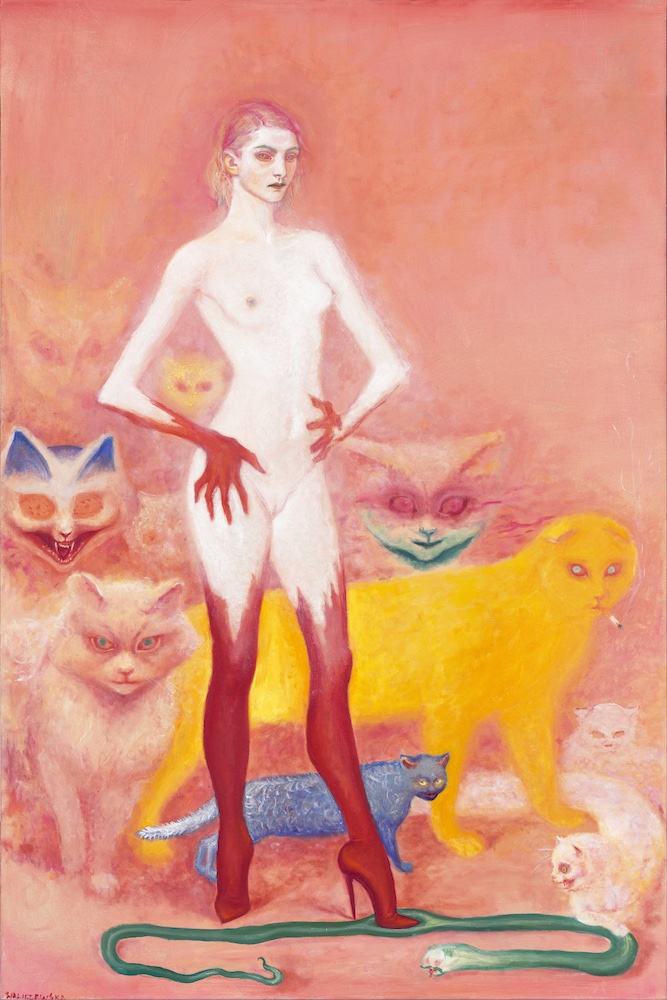

Hysteria is not a foreign preoccupation for artists. André Breton was fascinated by Freud and hysterics. It’s no surprise then that many works in the show have a surrealist bent. Aleksandra Waliszewska’s charming Leonora Carrington or Rosa Loy-esque paintings of part-women/part-animals are less animorph than centaurs. The brushwork is light and scumbly, and the palette is a rosy Easter egg with sharp, opaque blues and greens cutting through. The creatures and women radiate a fear-inducing power with eyes that burn red. They are prey-turned-predators.

At its most compelling, “It Smells Like Girl” gets playful and cartoony. Liz Craft’s sculptures (Large Ms. America I-II [2022], Medium Ms. America I-V [2022], and so on)—Ms. Pac-Man dressed in black robes—startle so aggressively that you can’t help but reflexively react. Some of the Ms. Pac-Mans, in an assortment of sizes, gather in a clump, while others break away from the group, multiplying across the gallery. Their black cloaks are fashioned to give the impression of short, stubby arms. These bow-wearing creatures with their strange garments point our attention in an array of directions—mourning, priesthood, the Supreme Court (Ms. America an RBG commemoration?).

It’s Meriam Bennani’s drawing-pad-sized colored pencil drawings, more than her sculpture, that catch my interest. I am transfixed by their slapstick beauty. In red, orange, and black, cigarettes and shoes get cut in half by a giant cadaver. Matchsticks sprout legs and look remarkably similar to K8 Hardy’s vaguely anthropomorphic sculptures in the adjacent room. The slapstick meshes with the, for better or worse, vaudevillian bent of “It Smells Like Girl.” Hysterical laughter, if you will.

Nadia Lee Cohen, Entitled, 2025. Photo: Genevieve Hanson. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch, New York.

In one of Isabelle Albuquerque’s three sculptures in the show, Head and Tongue, a wooden, bald head leans back, its mouth agape. When you peer into the open orifice, you see a lifelike tongue sewn together with red thread. We are left wondering whether the cut off and then reattached tongue was a self-imposed or outwardly inflicted act. Albuquerque’s reattached tongue materializes the relationship between language and the body. It serves as an apt parallel to the case of Breuer’s patient Anna O. (the most famous case study in Studies of Hysteria), whose ailments, both physical and mental—visions, paralysis, and the loss of language—were brought on by her caregiving for an ill father. A distinguishing aspect of the Anna O. case was her loss and reacquisition of language. She spoke four languages but, as her symptoms worsened, lost her native German and could speak only in English or not at all. At last, at the end of her treatment, Breuer reported that she regained her German. Anna O. herself described the treatment she received from Breuer as “the talking cure.” It is precisely language and its gaps that expose the state of the body, and vice versa.

Nadia Lee Cohen’s sculpture, Entitled (2025), is an interactive display screen of a bikini-clad woman who has seen better days. Her tights have a run, and her hair clumps, covering her face. As you look at and move around her, she responds by posing, cocking her head, and turning away from your gaze. Apparently, the longer the viewer interacts with this cybernetic Tamagotchi approximation of a woman, taunting, prodding, or comforting alike will inevitably lead to her death. I didn’t make it long enough to see this happen. The novelty of the encounter wore off too quickly. Cohen’s character is evidently in control of her own misery. It has been asked whether Anna O. was playing the role of a hysteric in order to seduce Breuer (a contested and dubious claim, possibly rooted in Breuer’s feelings about his patient). She claimed to be pregnant with his child (this development was left out of Studies in Hysteria), a return to the ancient Greek “wandering womb” theory of hysteria. This theater, no less hysterical in its own right, brings up the question of how much agency the hysterical woman has. In Cohen’s work, the hysterical woman is reacting to something invisible, internal. And while that’s in line with the language of the exhibition, I find this work on its own terms deeply uninteresting.

Jibz Cameron, Hoowah!, 2025. Photo: Charles White / JW Pictures. Courtesy of the artist and Jeffrey Deitch.

On a more effervescent note, Jibz Cameron’s drawing Hoowah! (2025) and her performance brought life to “It Smells Like Girl.” A cartoonish woman smoking a cigarette has a body divided into thirds (in classic exquisite corpse fashion) in an S shape, ending in a single red heel. The drawing is set in a zany old-timey Western. We need the fantasy, which Cameron delivers.

Cameron, in her alter ego Dynasty Handbag—a parody of an aging 1980s businesswoman, replete with smeared makeup and a penchant for the absurd and vulgar—performed a feigned docent tour for the show. Attributing each artwork to herself, Dynasty Handbag played the character of a delusional, ego-obsessed artist. She’s at her best when teetering on the edge of breaking character, as when she questioned Madani’s painting’s place in the show or did an extended bit on Jeffrey Deitch himself, asking audience members if they were him and pronouncing his name in increasingly jumbled and Germanic ways. Of all the work on view, Cameron offers perhaps the most contemporary answer to the somewhat tired premise of “It Smells Like Girl.” With Dynasty Handbag, language is always a Freudian slip, where improvised thoughts follow each other like somersaults, and the slip is more like slipping on a banana peel.