“Los Angeles is 72 suburbs in search of a city.” —Dorothy Parker

I like to go to parties. If you invite me, I’ll come. I never plan to stay long (“I’m just going to make an appearance,” I tell myself), but once I arrive, I end up having a great time and linger until some regrettable hour of the morning. I’ll dance if there’s dancing, sing if there’s singing, eat and drink whatever’s handed to me, and give 200% to a conversation with people I’ll never see again. I don’t discriminate; I’m equally happy to hear a stranger’s darkest secret or have the same boring conversation I’ve had a hundred times before. Which is why I can tell you with confidence: at every kind of Los Angeles party I’ve ever attended—dinner, rager, or “listening party”—someone will inevitably say, as if reciting a shibboleth, that “Los Angeles is a lonely town.”

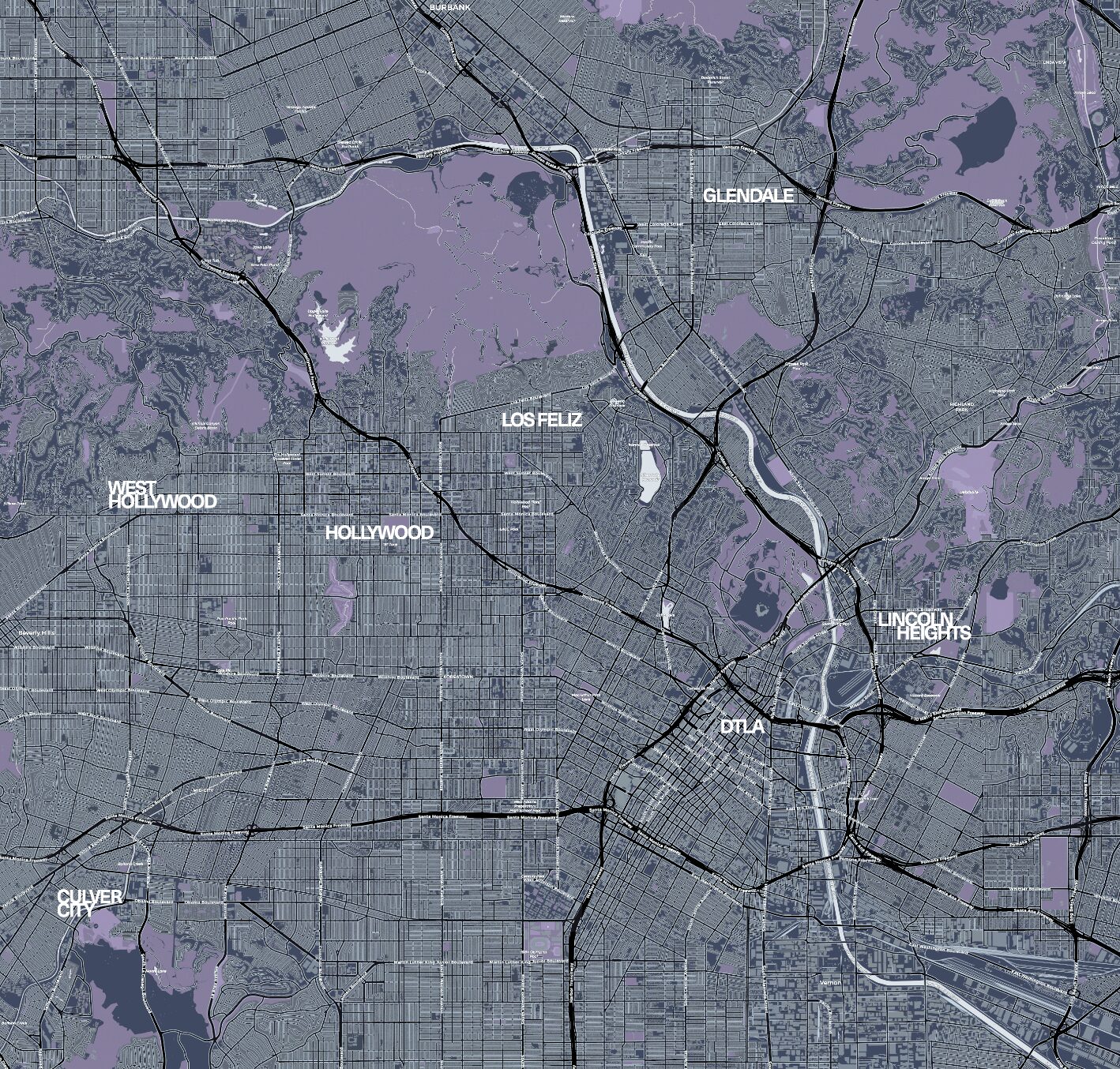

I’ve always found this proclamation kind of weird. Declaring a city to be “lonely” while in a crowd of people is odd behavior (like going to a bar and declaring it “sobering”), but beyond that, I don’t know what it actually means to say ours is a lonely town. I can understand how urban and suburban sprawl geographically isolate Angelenos from one another, but I suspect my interlocutors are referring to a deeper quality. They mean the feeling of leaving the glamorous celebration and driving home on a highway of wasted dreams, the same feeling Kerouac described when he wrote in On the Road, “LA is the loneliest and most brutal of all American cities.”

I’d pity the friendless for their suffering if I didn’t suspect that, on some level, they enjoy it. If LA is a lonely city, it’s because LA is an American city, and Americans—especially Westerners—love to be lonely. It’s not only aesthetic; it’s ethical. We simply don’t trust the logic of small, close-knit groups, which feel suspiciously European. Of course, the American cowboy myth has its manifold political and philosophical problems, and I doubt many readers of this magazine would identify as bootstrap individualists. Still, the fact remains that we live, work, and gather in a city built on the idea that being alone is morally superior to being together. That belief, perhaps, leads to a kind of social schizophrenia: our persistent feelings of being alone at the party.

The picture becomes even more complicated when you are an artist. The nature of our work is often solitary, but the purpose of the work is to communicate. The paradigm of art as self-expression—tied to the unique efforts of individual artists—defines the way visual art is written about and sold. But none of the artists I know here function as solo geniuses in a libertarian paradise. We live in a sprawling megalopolis, and when we quit the studio, we call our friends and see if they want to get Thai food. We gossip and kvetch and run ideas by each other and go to openings. Writing this in the thick of the fall art season, I’ve spent the past couple of weeks bouncing between previews and dinners, dutifully socializing per my job description. But on my misty early AM commutes home, I’m susceptible to the same angst as anyone else, and I do wonder: (1) if hanging out is a good thing, (2) does hanging out with other artists makes art better, and (3) if we take the first two for granted, how exactly should we go about hanging out?

I don’t pretend to know the answers to these questions, but I respect those who attempt to. A couple of weekends ago, following the opening of “Made in L.A.” at the Hammer, I joined a throng of people younger than me at a rival event, “Made in helLA,” which brought together the city’s avant-garde visual and alt-lit scenes for a 24-hour marathon of screenings, panel discussions, readings, poker, dancing, and a lot of standing around smoking cigarettes. Organized by the writer Sammy Loren, who also runs the clouty reading series Casual Encounterz, “Made in helLA” offered a punk curative to the heavy-handedness of the official art world—a message that art can be made, and people gathered, with barely any money or staff. I didn’t stay until 4 a.m., when a poet cooked a pancake breakfast, but I did attend a talk by wayward gallerinas and watched a video about dead beetles made by a young artist who identified as a self-taught entomologist (note: I love L.A.). I won’t lie: the party made me feel kind of old and worried about fire code violations (“I don’t want to die at Casual Encounterz Ghost Ship!” I kept shouting to my friends), but I felt grateful to this city and its artists for facilitating some kind of underground.

I’ve also gone to—or heard tell of—other sorts of makeshift gatherings: weekly billiards (“painter pool”), poker games, book clubs, and para-academic monthly salons where artists get together to discuss work they like. I know of at least one artist-focused Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. In this issue of Artillery, we reported a story on the 20th anniversary of Mountain School, a free L.A. alternative institution that began in a bar in Chinatown in 2005 and, for two decades, has championed the cause of “hanging out.”

Perhaps these sorts of gatherings feel all the more distinctive because L.A. is not New York or Paris, and because every time we gather, we fight the aforementioned cowboy ethos. As for whether any of this socializing makes for better artwork, I suspect it does. I know it makes life more livable, which isn’t a small thing, considering that we live in a moment of considerable economic and social panic. Both in the arts and the country more generally, people worry about the bottom falling out, about our way of life changing forever. The panic even touches social life: According to a recent report that inspired a tizzy of think pieces, this generation of young Americans spends 70% less time socializing than kids did in the early 2000s.

If this is really a moment of social and economic sea change, I think Angeleno artists are well-positioned to navigate it. This is, after all, a city of individualists who make our own fun. We don’t wait for permission to throw the party—or to leave it, to be lonesome once again