I’m not sure exactly when I accepted that the future of contemporary art belongs to the furries. It likely happened at the waterfront rave in Pittsburgh—where, flanked by gyrating, half-clad wolves and sexy tigers—I spent the late hours of July 4th lounging with a collective of anthropomorphic artists, dangling our legs over the dark waters of the Allegheny River and talking big ideas, until we were interrupted by a yacht full of blonde women in stars and stripes who, drifting past the rave, drunkenly yelled, “Happy Fourth of July!”

“Happy Fourth of July!” the equally drunk fursuiters yelled back. And then, as an afterthought, they followed up with cries of “Fuck America!” and amped up the hyperpop.

At least, that was definitely when I realized I was having more fun at the afters for an art opening than I’d had in years. The artists and I had made our way down to the waterfront rave for a much-needed cool off after leaving the crowded, vital, sweaty opening of “Room Party,” an exhibition featuring 60 furry or furry-affiliated artists working across sculpture, painting, drawing, video, zines, and performance. The show, co-curated by furry-identified artists Brett Hanover, Lane Lincecum, Cass Dickenson, and Paul Peng, occupied a smallish Pittsburgh project space, Bunker Projects, and ran concurrently with Anthrocon, one of America’s major furry conventions—a sprawling event that feels surprisingly smoothly integrated into the city’s Fourth of July celebrations. Everywhere I went in Pittsburgh, the locals seemed to know about furries and regard the convention basically benevolently. The opening night of “Room Party” coincided with a regular Friday night art walk in the gallery’s neighborhood and attracted a few non-furry-affiliates off the street, who joined an elbow-room-only crowd buzzing with the energy of online friends meeting for the first time IRL, regaled in plush finery.

Photo courtesy of co-curators Brett Hanover, Lane Lincecum, Cass Dickenson, and Paul Peng.

There are some good explanations and a lot more bad ones out there about what furry is, where it came from, and who is involved—a lot of people have a vague impression that it’s a kinked-up sexual subculture that involves people elaborately dressed as cartoon animal characters. But I’ve found that the majority of outsiders don’t know that the community is heavily gay/trans and that the investigation into cartoon-anthropomorphism has little to do with real animals and everything to do with a kind of level 3000 media-theory-identity-matrix thing that one of curator of “Room Party” described to me as “some of the gayest stuff out there.” Furry, as a subculture, began in the 1980s in Garden Grove, California, where a group of roommates started making comics that riffed on cartoon animal characters recognizable from pop culture. As the subculture grew beyond SoCal, participants mailed physical drawings to each other, and eventually aesthetic tropes emerged: Big-eyed wolves, foxes, weasels, and tigers. (Furries are mostly mammals, though there are also “avians”, reptile and amphibian “scalies”, and robot-like “protogens.”) What began as analog USPS network art grew exponentially once it hit the Internet, where Furry naturally aligned with chatrooms and forums such as DeviantArt. The conventions grew in tandem with the online community, from the first con held in 1989 in Costa Mesa, which attracted 65 people, to the current events held around the country that attract enough people to shift the economy of a city like Pittsburgh.

There are plenty of answers to the question of “Why do people do this?” but I like this heady summary, written by cultural critic Max Krieger in a recent review of “Room Party” that appeared in Bunker Projects’ eponymous magazine:

Anthropomorphism is an innocent, compassionate response to our innate existentialism. It’s how we project life outward and reflect its light back into that layer of the self that nothing else can reach. All living things are products of their circumstances; to commune with those circumstances in the instinctual language of personality is a conversational animism. Communally bricklaying these subjective anthro-experiences into a social language—and the cultural iconography, traditions, and structures therein—is the essence of furry life. The furry persona (fursona) is both a call and a response. In that sense, the fursona is not a replacement for the self, nor is it superior.

I’m not a furry, but I do go to a lot of art openings, and to explain what avant-furry art is and why I find it so vital, I should probably explain what it is not. It would not fit into the art world around which I usually circulate, the denizens of which would likely balk at the idea of going to a furry convention except to gawk. They’d be too busy hanging out in chic little bars on the coasts or affiliating with institutions whose names you’d recognize, and making/viewing paintings bound for the collections of people who got rich doing things it’s impolitic to mention. My day-to-day involves enjoying canapés with peers who have preferences in European knitwear. The watchword here is Taste. “Taste,” in this case, does not mean liking what you like. Taste means liking Agnes Martin.

Photo: Tommy Bruce.

I happen to like both Agnes Martin and a lifestyle that involves sheets with a high thread count, and so I don’t complain too much at cocktail hour. I see no problem with the whole scene—the whole NY/LA contemporary art circuit—except for its deep, life-curdling, stultifying irrelevance. It’s in poor taste to acknowledge the irrelevance. Maybe we ignore our condition because we believe in the potential transcendental genius of art, and it feels bad to impose such a pedestrian criterion as “relevance” on art that might speak to the eons. Surely, we wouldn’t want art to be pedantically about anything? So, we keep it all vague yet evocative, and preferably in conversation with the year 1945. If I’m sounding cynical, let me clarify: I appreciate this art world. I grew up in America and was taught to distrust Taste and pray to a God who would not approve of Agnes Martin. Learning to love the modernist canon* freed me from an equally problematic set of populist and crypto-religious assumptions about who and what has the legitimacy to exist. It’s just that it’s all a bit tired, and I’m not sure anyone genuinely wants to be in the VIP lounge at Art Basel, even if there is free booze.

So, I’m not here to tell you Furry art is better than all that because it’s the underdog, or made by bon sauvage outsider artists, or in opposition to the tired strategies of Modernism, even if those things might be partially true. While the works in “Room Party” might not quite fit on the walls of Hauser and Wirth, my binary between art world and Anthrocon is necessarily a bit false because there is no real “outsider” art in our image-drenched culture, and at least some of the artists involved in this show and furry more generally hold MFAs or moonlight (daylight?) as art professionals.

Photo: Tommy Bruce.

But trust me that the feeling is different. What feels substantially different about a show like “Room Party” is perhaps just its necessity, not only to the furries (for whom this sort of self-expression is at times a matter of queer life or death), but for the rest of us. I want to make a case for this art’s relevance to Furry and human alike. The ninety-odd works of art at “Room Party” are some of the best I’ve seen in years, in part because none of them turn away from the fact that it’s 2025, not 1945. Also, they’re so weird and fun and maximally gay and highly specific. To quote writer/artist Chris Kraus, “Our specificity is all we have to offer.” What the furries understand is that we artists working today have to proverbially choose a fighter (and rehashed minimalism/formalism is not a fighter):

Our choices are:

We can commit to a tech-accelerationist sublime—a dark vision of technological/social change and the end of history, which leads to us eventually shipping consciousness to Mars in shitcoin-funded space vessels; or

We can accept our condition as hopelessly stranded between the virtual and IRL, accept the depersonalization and disembodied trans-ness of it all, follow our desires, and remain here on Earth to attend the ongoing rave reembodied as sexy cartoon tiger avatars.

“That’s not true, Eileen,” you’re maybe saying right now. “I’m not especially online, and I don’t even know what you’re talking about. I check The New York Times once a day, and I enjoy many, many outdoor hobbies with my very normal sons. I like a nice bronze. Not to mention, I’m in love with my wife!”

All I have to say to this sort of objection is: Twitter is running the American government, and you are Online whether or not you realize it, and whether or not you want to be. Your kids (and wife!) have seen things on the Internet you can’t even imagine. It’s better to accept it.

I don’t know how to write comprehensively about a group show that included over fifty artists and nearly 100 artworks, many of which were in book, video, and performance form. I attended the show two days in a row and barely scratched (pawed?) the surface. So I’ll just describe a few of my favorite artworks from “Room Party,” in hopes that this will give at least a partial argument for why I hope you, Reader, will join or at least embrace Furry art as the neo-avant-garde and leave behind any nascent fantasies of burning down the earth and shipping yourself to a space colony.

In no particular order, here are a few works that stood out to me:

IV Nuss, I Really Want To Go To Anthrocon 2025 But I’m Too Scared To Enter The States With My Tranny ID, 2025.

I Really Want To Go To Anthrocon 2025 But I’m Too Scared To Enter The States With My Tranny ID (2025) by IV Nuss

This video was screened as part of a series of performances and lectures and was billed as a “live performance” even though Nuss was clearly absent. Nuss is a German poet and artist whose work approaches the universal and transcendental by way of the mundane and pedestrian. In the video, she pretends to buy plane tickets and pack for a trip to the US (“I’ll be with you soon”) but notes certain obstacles to the journey—the US government, finances—and reflects on how we might be together at a distance. These days, everywhere seems to take place in the same sort of nowhere-place—a hotel lobby, for instance—where there’s an intimacy in the shared blandness of it all. Haven’t we all been to the DoubleTree Hotel? Haven’t we fallen in or out of love there?

Nuss also invents the “layers of the fursuit”— the outer layer, the outer-inner layer, the strategically placed layer, “negative cerberus,” “Selva Obscura,” “Swoon As You See Your Own Death,” and the Endo Sphere—and compares them to the layers of a suitcase she pretends to pack. It’s funny, weird, and moving.

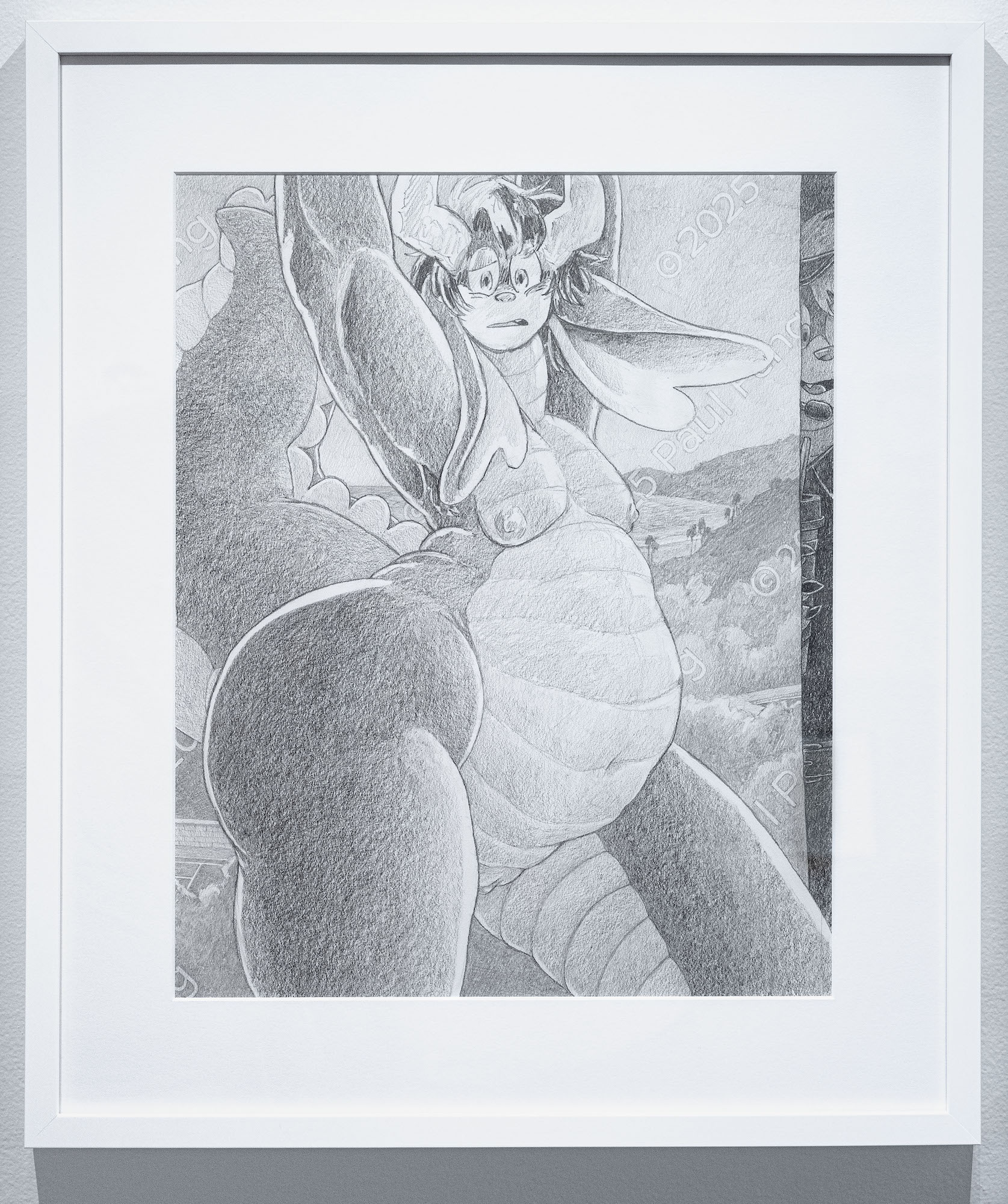

Paul Peng, Green Screen Model with Stock Photo and PA, 2025.

Green Screen Model with Stock Photo and Pa (2025) by Paul Peng

Peng, another co-curator of “Room Party,” makes these extraordinarily careful pencil drawings as notable for what they show as for what they hold back in terms of color and form. The razor sharpness of Peng’s work comes from the strength of the compositions, which counterpose moments of erotic revelation and withholding. It’s furry noir—the illicit image glimpsed in a rectangle of muted light.

Juliana Huxtable, Infertility Industrial Complex (still), 2019.

Interfertility Industrial Complex (2019) and Poster Art by Juliana Huxtable

Of course Juliana Huxtable, one of the most lithe artists working in the aforementioned “art world,” is early to the fringe party. Her video Infertility Industrial Complex (which originally showed at Reena Spaulings in 2019) probably has the most to do with actual animals of any of the work in the show, in that Huxtable plays with the specter of industrial agriculture and her own upbringing in Big Ag Texas. In the sultry tones of a phone sex operator, her mouth dominating the frame, Huxtable speaks to the uncomfortable borderlands of sex and consumption, animal and human, life and death. In the stairwell leading up to Bunker Projects, a few posters (“THE SUNDAY INDEPENDENT: FURRIES GONE TOO FAR!”) made by Huxtable for the same exhibition set the tone: Impermanent. Punk. Here for a good time, not a long time.

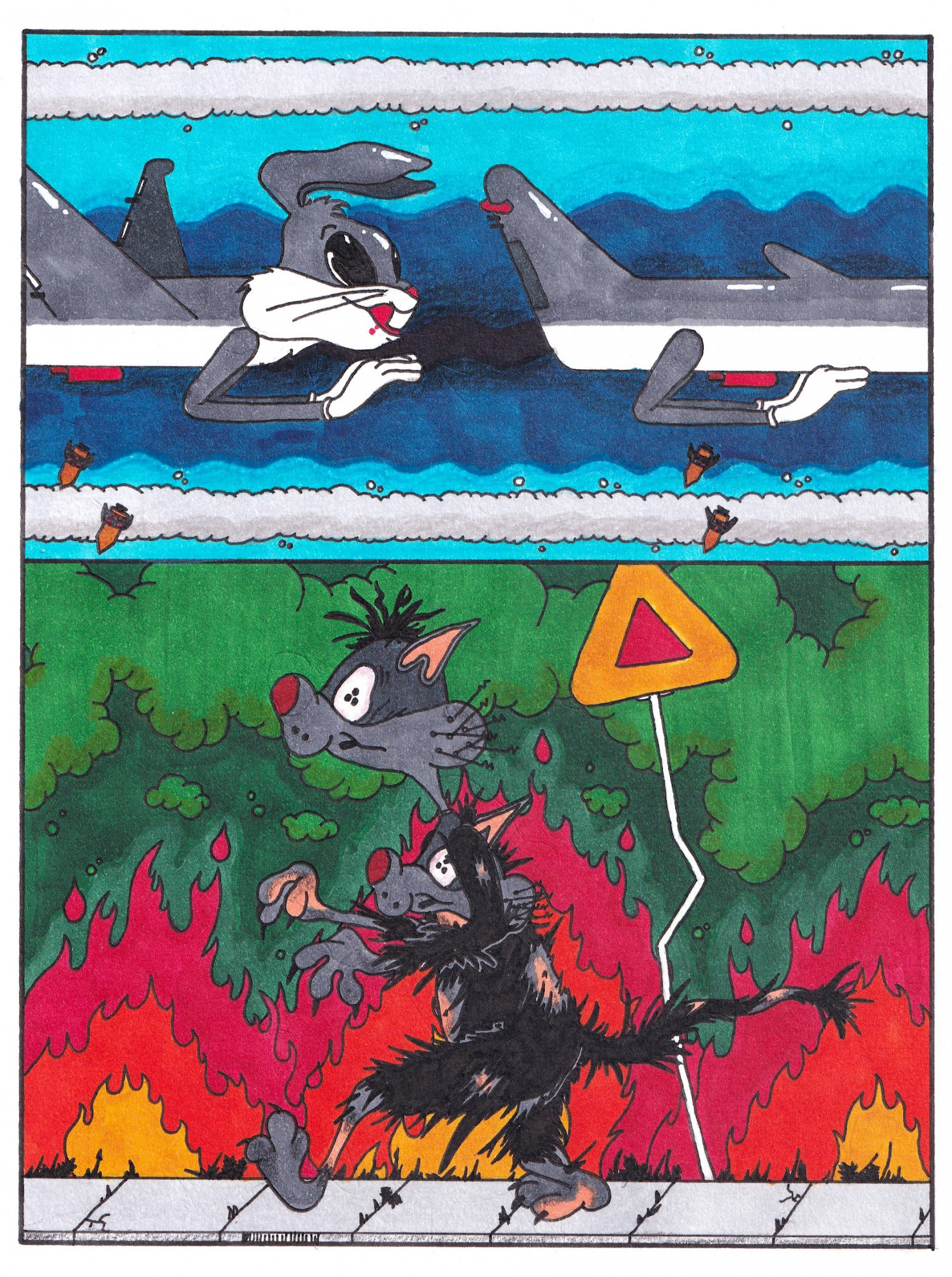

Izzy Paige, Shellshocked Sylvester, 2023. Courtesy of Room Party.

Pump Rabbits (2024) and Shellshocked Sylvester (2023) by Izzie Paige

These drawings are so good! And are they some of the most American artworks I’ve ever seen? They feature a penultimate American scene: A gas station with pumps made of cartoon rabbits. Airplanes (also rabbits.) The burning hedge and overgrown sidewalk, strangely flat and residential. I don’t know any of the specific inspiration for these—and they seem pretty high context—but what draws me in is how pleasurable they feel, their heft and hue and line, the combination of familiar and dreamlike terrain, and the nostalgia.

Maya Ben David, Air Canada Gal (still), 2017.

Air Canada Girl (2017) by Maya Ben David

If you were online enough in 2017, you may have seen a version of this video—the Toronto-based performance and video artist Ben David cosplaying a very femme Air Canada flight, dancing dramatically around a darkened room—go viral on Instagram. I did not see it back in the day and am happy to have seen it for the first time in the context of a compilation of videos that also included her cosplaying her own GoodLife Fitness gym bag and another of the two aforementioned characters playing baseball in a scene reminiscent of the baseball scene in Twilight. The artist also graced “Room Party” with an elaborate live presentation/lecture of narrative drawings of characters she’s invented called “Scrump Runts”—furry, minute, sexual animals that live in a creek in Toronto, that have names and a caretaker, love and are loved, and continue to evolve in a realm slightly askew from our own. Ben David is one of the few non-furry artists included in “Room Party,” but she’s earned her stripes as a fully Online anthropomorph dealing in some of the same existential territory as her peers in the exhibition.

Mark Subrovich, SELF PORTRAIT (EMOTIONAL SUPPORT DOG), 2024

Self Portrait (Emotional Support Dog) (2024) by Mark Zubrovich

I love this painting of a canine knight, which fits perfectly above the venue’s mantlepiece. I admire the illuminating rays, the detail of the armor, the funny but somehow sincere historical elevation of it all. It reminded me of how I heard someone describe the premise of the whole show as “not an art exhibition happening in the real world, but the art exhibition that the characters in a cartoon attend.”

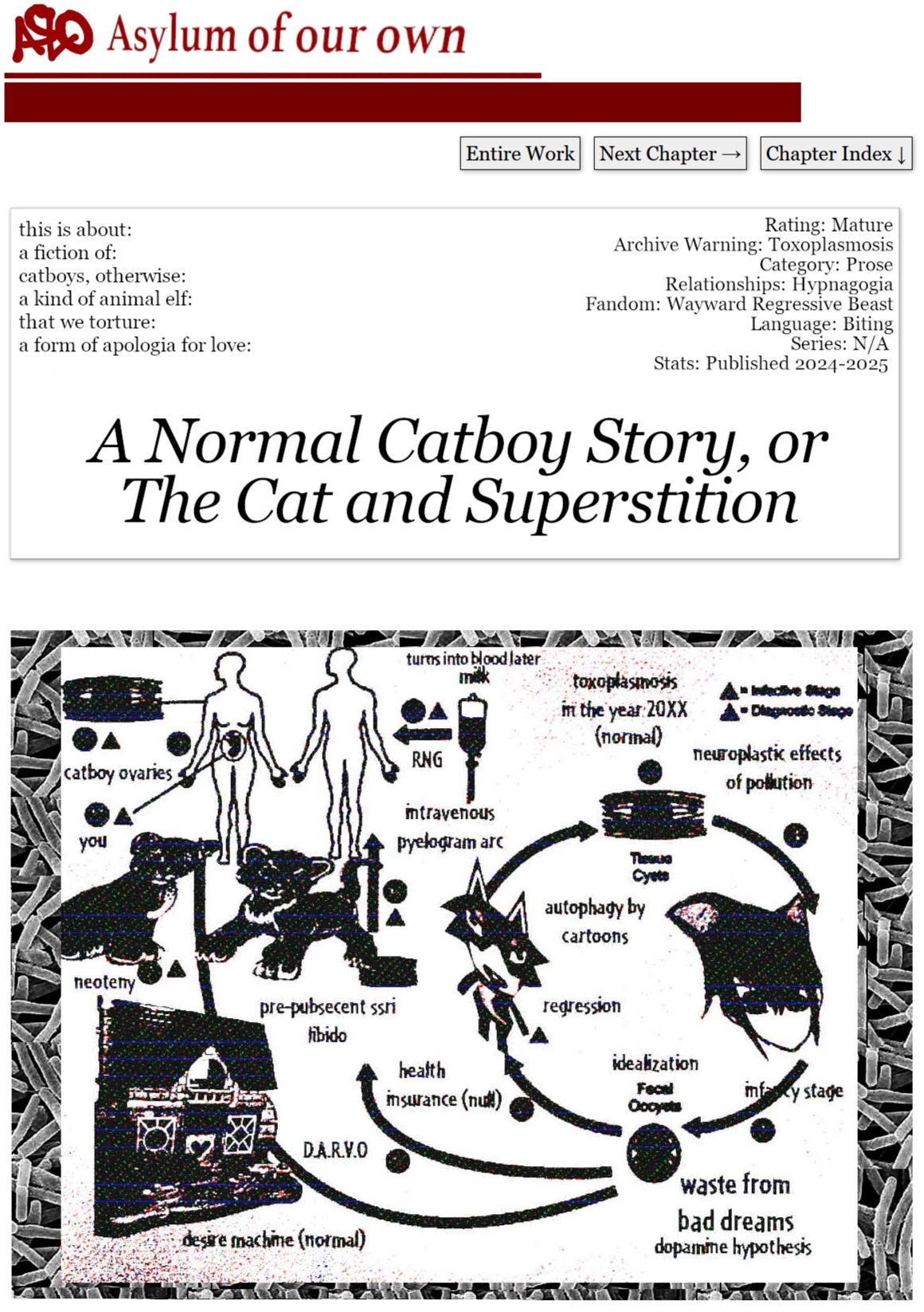

A Normal Catboy Story Or The Cat and Superstition by blake planty.

A Normal Catboy Story or The Cat and Superstition by blake planty

As previously noted, Furry began in the 1980s, on paper rather than in JPEGS. It seems natural, then, that there would be a lot of good furry zine art. “Room Party” displayed shelves of the stuff, way more than I’d be able to cover here. One of my favorite zines that combines drawing and writing is the deeply elaborate Catboy Story, a glitched-out series of flowcharts and stories that feel pulled from a half-paranoid lucid nightmare of becoming-animal. Kafka could never. I’ll just say that it’s very desire machine (normal) and recommend downloading it from planty’s website.

Brett Hanover (with Eve Hoyt), Digger, Listener, Runner, 2025. Photo: Tommy Bruce.

Digger, Listener, Runner (2025) by Brett Hanover (with Eve Hoyt)

Furry is about sex and desire, but at its core, it’s really about friendship—about the rare occasion of becoming actually

visible to another person. Making art is a fight to be seen, to determine the image of ourselves rather than exist constrained by the distorted images that dominate media; images that have nothing to do with what it actually feels like to be human. To live without that is death-in-life. What do we wish for our friends, who we love and who make our life worth living? That they stay alive in every sense. So, that is all to say that I really liked this work of neon text art that co-curator Hanover made for the windows of “Room Party,” drawn from this quote from Richard Adams’ novel Watership Down: All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you, digger, listener, runner, prince with the swift warning. Be cunning and full of tricks and your people shall never be destroyed.

May we be wise enough to embrace art as cunning, strange, and necessary as that in “Room Party.”