Duelling Reviews

DUELLING REVIEWS: MARY CORSE at Pace Gallery

A central figure in Southern California Light & Space art, Mary Corse is not a conventional example of the practice, but she is an orthodox one. That is, since her student days, Corse has applied materials and techniques readily associated with “perceptualist” abstraction to ends that exemplify, and indeed have helped to define, its precepts. Corse has realized works and series in standard and experimental formats. That said, she considers herself first and foremost a painter (albeit with no need to rationalize her quasi-architectural installations as “painterly”). The condition of painting demands its own orthodoxy, and from this gospel of the picture plane radiate all the visible (and a lot of the not-so-visible) Western orthodoxies about 2-dimensional art of a certain substance and breadth.

To denote Corse and her art as “orthodox” is in fact to praise it; to acknowledge the contribution it has made to the tendency and the consistency she has maintained over the duration of her career—the Corse course, steady as she goes. The secret ingredient in her work all along has been glass microspheres, embedded in different patterns, layers, depths, skeins, and admixtures in order to embed light in her surfaces and thereby control the ways light ultimately reflects off those surfaces. Corse has established herself as maestra of the microspheres, activating and misleading the eye in myriad subtle ways, seeking to deflect the certainties of a sunny day or brightly lit interior or pair of contact lenses so that light itself becomes a hall—or ball—of mirrors.

Mary Corse, Untitled (Electric Light), 2021. © Mary Corse, Pace Gallery.

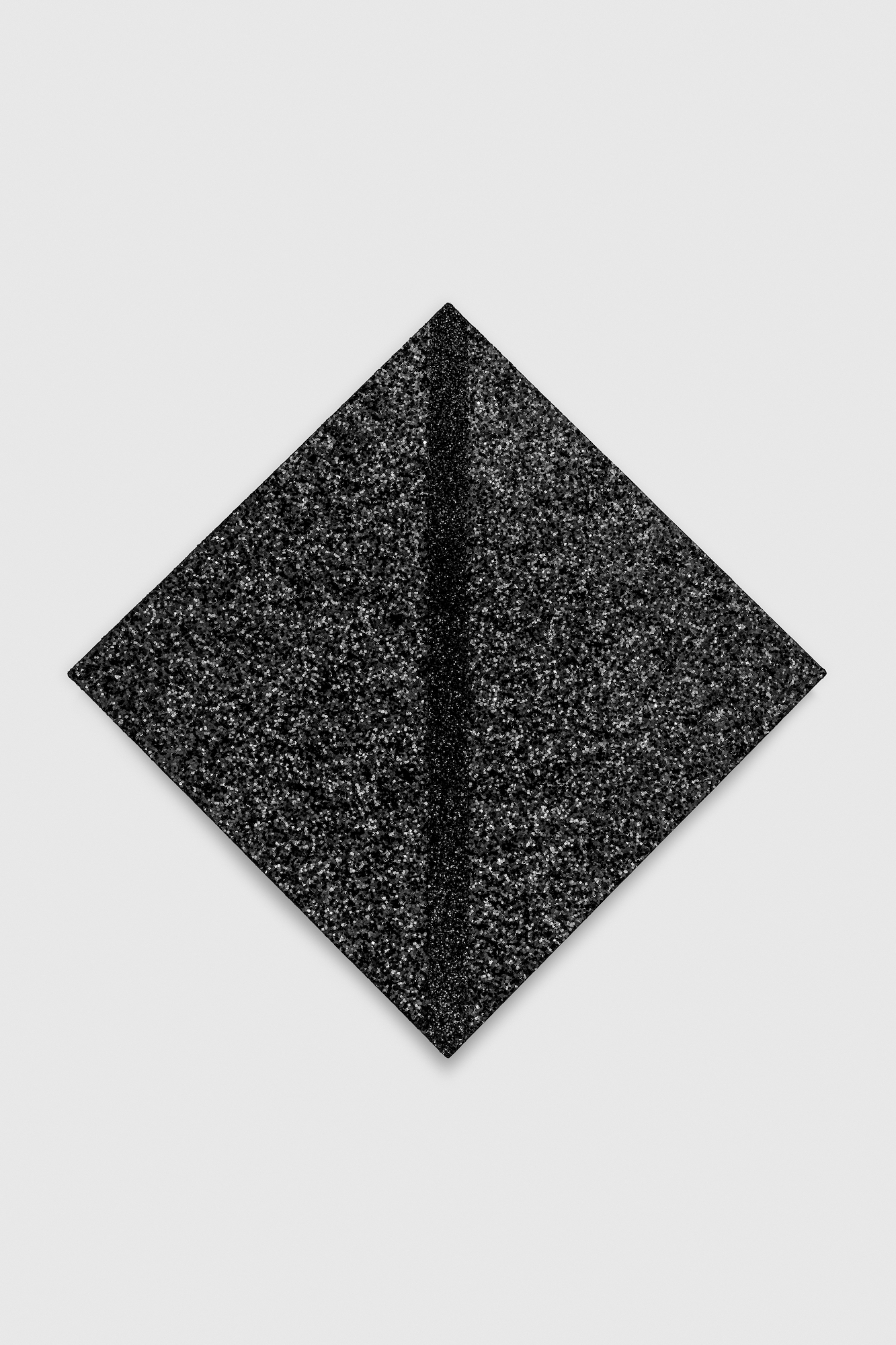

Corse’s continued identification with painting, however, marks her work with the heritage of two orthodoxies, the one several centuries old out of Flanders and Venice, another several decades old out of Santa Monica, and the other out of Venice. It is this twinned artistic DNA that she evidences in the body of work largely comprising this show. The forthright motif—an almost heraldic one of a diamond shape vertically bisected by a contrasting stripe—originated in Corse’s Chouinard days and has recurred occasionally since, but never to this extent. All these paintings—and yes, they are nothing if not paintings—were fashioned this year and last. Their display is augmented by two light rooms, one that murmurs exquisitely with a smoky radiation and the other a playroom-like box that at once amplifies and engulfs a silvery reflection of the viewer (or two) on the far wall.

A couple of the paintings themselves play now-you-see-it, their silvery microsphere surfaces all but erasing the vertical element. Otherwise, the lozenges are painted in solid bright colors contrasting with the similarly bold stripes, some of which are flecked with microspheres that twinkle individually. Light & Space immateriality plays second fiddle in these bold panels to an elegant minimalism and vivacious palette, which conjure geometric stylizations prevalent in New York and especially Europe in the 1960s. As mentioned, this aesthetic, and specifically this compositional template, emerged during Corse’s mid-60s studies. Even if she took no influence from Max Bill or Chuck Hinman, Corse picked up on the Zeitgeist and ran with it. She turned such geometric art into Light & Space the way her peers did: by staring into visual expanses and casting the eye into the void. It’s not only historically fitting that Corse’s stark bifurcated diamonds should bask in the vibrating natural light of James Turrell’s gallery interior, but also optically astounding.

Minimalism is like somebody else’s drugs. Somebody rich. They’ll say their drugs are worth more than their weight in gold, catalyzing a powerful realignment of perception, enabling communicating with the primal essence of being, and a powerful symbol of all the ways they themselves are different from all you squares: To the rest of us, they’re just one of the more tedious ways to broadcast status. What can we do but congratulate them on scoring enough free time to jabber for hours about things they won’t remember to guests that aren’t listening or enough free space to devote an entire room to a pricey rectangle? Like the great Buddha Siddhartha Gautama beneath the Bodhi tree, the Minimalist has transcended the entertaining vulgarities of this world and now sits divinely diversion-free before the omnipresent gift of nothing. Have you ever really looked at nothing? Well, here’s a visual aid.

These mannered variations on emptiness are accompanied by a sixty-year-old body of literature whose volume and collective prestige dare you to declare them irrelevant. What unphilosophical rube would be rube enough to claim they see nothing in a painting where there’s nothing to see?

“Maybe, but don’t you find all that silhouetted shrubbery detracts from the pure contemplation of light and of space and makes you intensely anxious?” they might say.

“Not really,” you might say, “It’s a weekend and I’ve got nothing better to do but be in an art gallery. I find, given that, thinking about light and space is pretty easy.”

“Well, I don’t,” they’d say, “I hear there’s an uncut box of it around here somewhere.”

Mary Corse, The Halo Room, 2023–2024. © Mary Corse, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Corse went to great efforts to hide or eliminate cords from her lightbox pieces—because it is somehow less about perception, physics, and subjectivity if you can see the cord.

I do not believe Corse or her fans are charlatans—they’ve both had decades to get interested in something else if they really wanted to be. They are sensitive souls who simply cannot filter life enough to see light or space or grids or planes when they appear out on the street.

Art historian and curator Kim Conaty notes that in Corse’s world, “The same work can appear dramatically different under varying light conditions and from alternate angles, a point that underscores Corse’s intention to create both an active and subjective viewing experience.” Conaty fails to note that this same effect—simple geometric shapes and brush marks revealing themselves as you shift your position relative to the image and the light source—is achieved by every freshly-painted house you’ve ever seen. Likewise, not noted is that the glitteringly textured, light-bending “glass microspheres in acrylic”—the signature industrial material that distinguishes a Corse painting from the work of anyone else who saw early Frank Stella and never got over it—is almost visually indistinguishable from sandpaper or skaters’ grip tape.

Mary Corse, Untitled (Black Reflective Diamond with Inner Band), 2025. © Mary Corse, courtesy Pace Gallery.

Corse opines in a 2021 interview that her work is about truth, beauty, and spirituality. If so, that cannot possibly be because of what is in them, simply because what is in them is all over any given walk across any modestly well-maintained parking lot: basic geometry, textures lit from revealing angles, stripes. Corse’s angelic ambitions seem to be more tied to what is excised from the work: reality, association, invention, the possibility of dirt. When Corse says, “Someone at the other end sees something different than you. You become conscious of perception making the painting,” she doesn’t imagine an audience that could be aware of that without her fastidious acts of de-invention. Even if we accept Corse’s goals as interesting, they were achieved long ago (though the oldest work in this show is from 2021). There’s nothing here that couldn’t have been made at any point since Corse’s career began in the mid-’60s, aside from the architectural installation Halo Room (2023–2024), which could’ve been made at any time since the mid-’70s.

Any pleasure here is akin to whatever conservative thrill is to be derived from a freshly cut square of lawn or well-made bed. Wealth has been expended to hew order and blank-slate conditions from the confusion and chaos of an icky real world where the act of abstracting one of an object’s properties from the many others organically present would, without the Minimalist’s good work, require thought or imagination. Here is red and nothing but, here is white and a black stripe, here is a rotated square. Here is a visual metaphor for money’s ability to buy peace of mind. Abstraction, here, is not a liberation from the constraints of mimesis, but an act of rarification, a visual expression of the work’s value as status symbol: This is outside and above the world, and so long as you are in a white room with it, so are you. Here, the barely adorned canvas can achieve its most honest function: A blank screen upon which the viewer can project their pretensions to enlightenment.

Again, like someone else’s drugs, great claims are made not just about efficacy but necessity:

“Do you ever feel that it’s all too much?” they say.

“Sure,” you say.

“Yeah, man! So distracting! The traffic and the war and the chaos and the racecars and the chocolate and don’t you just wish it would all disappear?”

“Actually, I kind of like chocolate,” you think. But you keep that to yourself because they seem to need an audience.

“Well, I’ve found a way out! A way to clear away the junk and focus on what’s important!”

And you ask what that is, and they say Adderall. Or Xanax. Or cocaine. Or Mary Corse at Pace Gallery. And they probably do need it, because they seem like they’re wound way too tight and definitely need something. The Minimalist is, unlike most people, not bothered that there are bad things instead of good ones, but rather bothered that there are things at all.

Alright, that’s an exaggeration. Corse was associated with the Light and Space Movement. Light and space are both things, and this brand of Minimalist approved of both. Though one might assume devotees of this movement would find more than enough of their favorite things amid the sun-bleached lots of Southern California, the disciples of Light and Space remained obscurely unsatisfied and were moved then to create brand new objects showcasing the fact that there is light and there is space. Do art-historical claims about the centrality of their exploration need to be taken any more seriously than someone who takes a lot of mushrooms and calls themself a “psychonaut”? Signally, both postures emphasize the method of exploration rather than any hope of something being found.

The ideal audience for MCorse’s show at Pace Gallery would be someone hypnotized to the point of stupefaction by Untitled (Electric Light) (2021)—a hanging lightbox much like something you might order to decorate your high-end sneaker store just before stenciling the word “Nike” across it—yet completely unmoved by what they’d see if they just spun 180 degrees: no piece of art at all, just the frosted-to-gray silhouette of vine and tree framing softened oblongs of flat white daylight imparting a glow to the tastefully-blurred window that looks into this part of Pace Gallery every day of the year.

“Isn’t that all light and spacey?” you might say, pointing to this window.