The night I saw Kaoru Ueda’s self-titled show at Nonaka-Hill, I found myself later at a friend’s house watching YouTube videos of marine life. The viewing experience of the vibrating patterned creatures felt nearly identical to Ueda’s obsessively precise paintings of food and other objects floating on off-white or gray backgrounds. Ueda enlarges his subject matter to sometimes overwhelming proportions, with no glint of light too inconsequential to be left unexamined. To zoom in is to go to the bottom of the sea.

Based on photographic negatives and initially appearing photorealistic, the twenty-one paintings on view dissolve into infinitely associative spiky, abstract forms. In Raw Egg J (2018), the ooze of a cracked egg becomes both floral and veiny. Elegantly delicate, but also unnervingly resembling the body, the paint mimics the materiality of a raw egg. Light reflects off the clear albumen, creating variegated ropey, entangled tubes in sunset shades. Ueda is preoccupied with eggs, along with any gelatinous or membranous material. And while deceivingly buoyant and plump, Ueda’s objects become hardened and still with extensive looking. A bidirectional material change occurs between liquid and solid and every in-between state. Bubbles are heavy, and glass (in Broken Bottle E [1983]) turns into a bubbling substance. Each confection has its own distinct terrain, whether mountainous, cavernous, or oceanic.

Aside from Ueda’s ability to render the familiar as strange, there are more obvious surreal elements in this body of work. A knife and fork cut a sponge in one painting, and, in another, a photo (unintelligibly and disturbingly of Ueda’s family) is set ablaze as it is being cut in half. The sponge is a buttery orb—a sea sponge, in fact—plucked from its habitat and eaten for breakfast. The strange elements in these paintings offer a satisfying break from Ueda’s repetitive jam, jelly, and marmalade on spoons, but the key to what he’s doing lies in his bubbles.

Kaoru Ueda, Raw Egg J (detail), 2018. Courtesy of Nonaka-Hill.

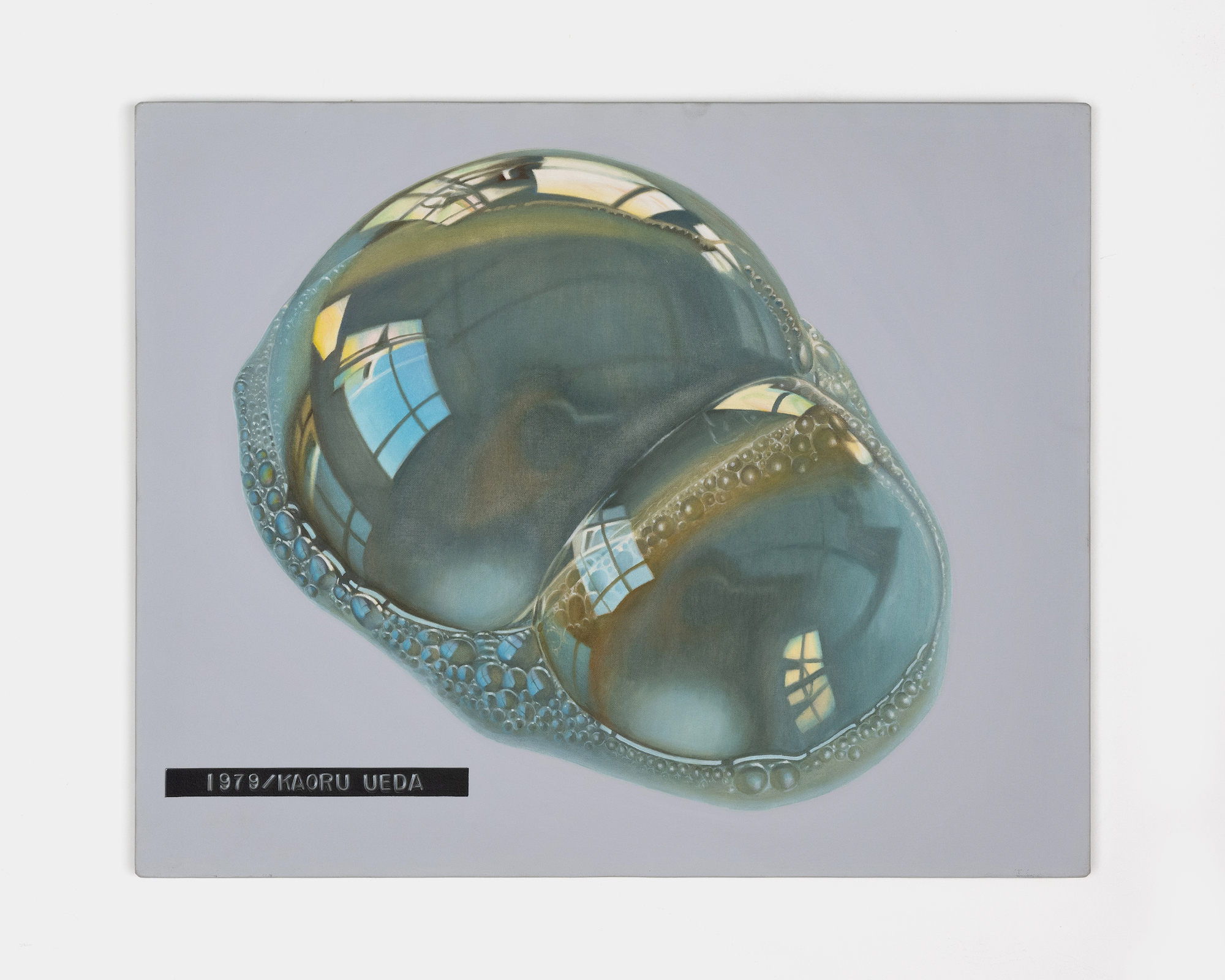

In Soapsuds A (1979), we see two voluminous bubbles beginning to split off from each other. The two main mounds are surrounded by their multiplying miniatures, like fish eggs around their mother. The bubble’s reflections create its convex form, and in them, we are able to gaze upon a distorted midday room. Windows are represented by blues and yellows stretched across the bubble’s surface and repeatedly appearing as rectangles in the surrounding foam. Though the image is visually murky, in the reflection we can make out a spectral hand resting on a camera lens. The artist himself has appeared.

The immensely popular YouTube channel showing sped-up footage of coral reefs is called “Bubble Vision.” This also happens to be the name of Hito Steyerl’s seminal lecture on bubbles’ place in art history, virtual reality, and surveillance technologies. Bubbles as a symbol are elastic. They bend toward the inflated, the youthful, and the tragically fragile. Evidently art historical, Ueda’s paintings fit into the lineage of the bubble in Dutch vanitas paintings. Homo bulla, or “man is a bubble,” underscores the fleeting nature of human life as allegorically represented by the bubble. Often accompanied by children in paintings, the bubble possesses playful associations that contrast with the imminent and threatening guarantee of being popped.

Ueda follows a more optimistic vision of the bubble and one that is closely tied to color. In Walter Benjamin’s “A Child’s View of Color,” he considers the child’s affinity for the rainbowed color variations of a bubble. Children’s relationship to color, he argues, is distinct and independent from the object that contains the color. He writes, “But children also elevate it to the spiritual level because they perceive objects according to their color content and hence do not isolate them, instead using them as a basis from which to create the interrelated totality of the world of the imagination.” This is precisely what Ueda is doing. The bubble, through the careful consideration of its colors, becomes a symbol of cyclical interdependence beyond a singular world. Instead of being fragile, the bubble is unbreakable.

Kaoru Ueda, Soapsuds A, 1979. Courtesy of Nonaka-Hill.

In the contemporary painting landscape, from Papademetropou-los to Koons, bubbles abound, yet don’t always possess anything beyond a symbolic pointing at the fantastical or acting as a fraudulent crystal ball. At risk of overstating what Ueda’s paintings are doing, they create an oceanic feeling, a spiritual oneness.

Ueda’s work resembles American pop art with its predilection for consumer products and bright colors. The earliest work in the show, from 1972, and the most visually distinct (and least interesting) depicts women’s tan pumps stamped “Bilbao” on the interior sole. The more compelling pop art element is a trompe l’oeil embossed label with the date and Ueda’s name placed on the bottom of many of the paintings—a lighthearted intervention to the painting’s surface. A visual branding joke, it is also a questioning of perception. Aren’t all of Ueda’s paintings trompe l’oeil? For Ueda, illusion and reality commingle and coagulate.

Nonaka-Hill has put out another gem. The gallery’s “best cleaners” sign in lieu of branded signage is a cheeky misdirect. Or perhaps it is an honest descriptor, and Nonaka-Hill are the best cleaners in town. In the case of Ueda’s soap bubbles, they certainly are.