Navigating the tension between impulsive expression and mastery of one’s craft is a fundamental aspect of the artist’s journey. A similar tension underscores the construction of personal identity that defines adolescence, and hence, the Orange County Museum of Art’s 2025 California Biennial was wise to set its sights on the Golden State’s rich youth culture. The group exhibition, subtitled “Desperate, Scared, but Social,” advocates for a new kind of nostalgia—one that honors the beauty of the past while embracing roughness and raw honesty.

I’ll admit that, upon learning of the show’s youth-centric gaze, I initially feared that it might play into the institutional mythologization of Gen Z and Gen Alpha, commonly fetishized for their coveted “digital native” status. (No hard feelings—I myself was born in ’99.) Refreshingly, “Desperate, Scared, but Social,” which highlights 12 contemporary artists plus themed collections of older works, celebrates teenagehood from an intergenerational perspective. In addition to platforming talented young artists the Linda Lindas, whose riot grrrl stylings are rooted in the traditions of decades past, the OCMA pays homage to the juvenilia of various local icons, from OC punk band Emily’s Sassy Lime (whose debut album lends the exhibition its name) to multihyphenate storyteller Miranda July to award-winning author Brontez Purnell. Adult artists who center youth and young adulthood in their current work are also featured. In a particularly innovative variation on the theme, OCMA even granted select students the opportunity to curate their own galleries-within-a-gallery, upholding criticism as its own art form.

Miranda July, Early Performances (still), 1997. Courtesy of the artist.

Every art museum serves as an implicit statement on the importance of the archive, writ large. But the California Biennial recognizes personal ephemera, the type that all too often ends up gathering dust in desk drawers, as worthy of elevation. The documentation of daily life through journaling has been bound up with the concept of adolescence since it emerged in the early 20th century; of course, artists never stop obsessively recording their inner lives, eventually transmuting their thoughts into art for public consumption. “Desperate, Scared, but Social” poignantly tracks this evolution via a showcase of Deanna Templeton’s work, pairing the photographer’s years-old diary entries with her portraits of modern teenagers. Reports of typical interactions with crushes (if making out with members of the Damned can be considered “typical”) are interrupted by stark records of meals (“2 chicken wings, ½ artichoke, 2 pieces of toast,”)—reminders that adolescence is characterized not only by bursts of passion, but also by bouts of exacting cruelty. Captured in black and white, many of Templeton’s subjects, street-scouted along the Huntington Beach Boardwalk, look jaded rather than ethereal: Frizzy hair, acne, and uncertain expressions reveal the weight of their emotions, saving them from slipping into Manic Pixie Dream Girl Territory. Messages Sharpied onto their skin—“Single,” “Feed Me,”—reveal both their agency and their vulnerability.

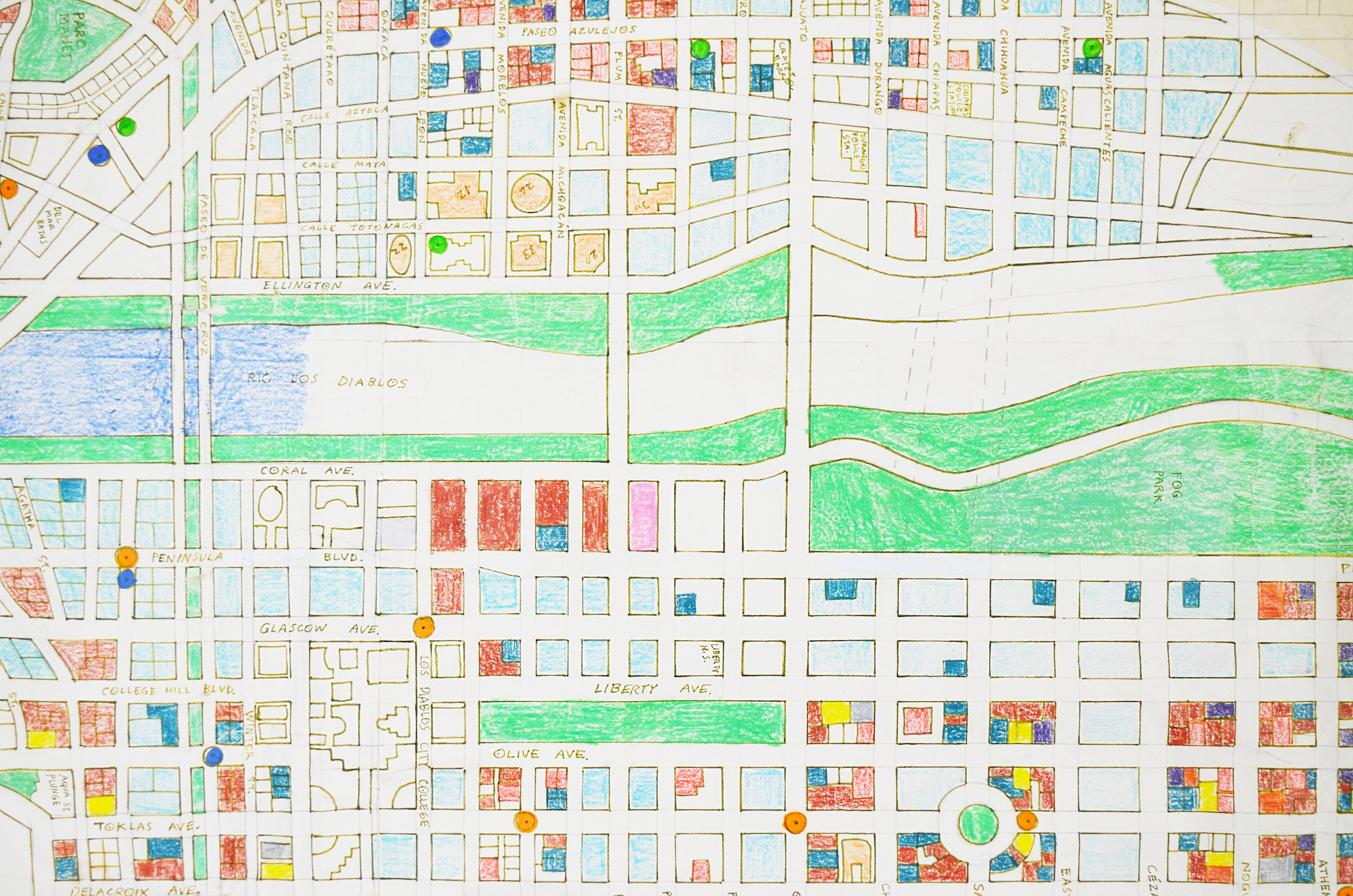

Joey Terrill’s Los Diablos, ongoing since 1969 (when the artist was only 14), depicts a more hopeful way of taking inventory. A meticulous archive of Los Angeles locations consisting of hand-drawn color maps and loose-leaf directories, Terrill’s project is so detailed as to induce a meditative state. Information that might read as dry if printed neatly in a directory takes on a new meaning here, mutated by Terrill’s labor of love. It’s said that naming is a form of ownership—following that train of thought, cataloguing can transcend mere functionality to become a creative act, calling a deeply personal alternate universe into being.

Other segments of the exhibition emphasize the archive as treasure trove—think locker doors studded with magnets and shoeboxes of ticket stubs tucked beneath mattresses, VHS tapes lost and found. The wing dedicated to Emily’s Sassy Lime successfully transforms the dreaded “white box” into an artsy high schooler’s private hideaway; a canopy bed strewn with artifacts ranging from guitars to snack tins serves as a spiritual anchor (or altar?). A labyrinth of bookcases lets patrons browse memorabilia from band members Emily Ryan, Amy Yao, and Wendy Yao. One special case is dedicated to Ooga Booga, a nonprofit initiative that provides topical reading materials for museum and gallery visitors, organized by Wendy herself. The bounty of books (including recent releases from indie presses such as Semiotext(e), a stapled collection of Ryan’s short stories, and a still-relevant “Feminists Against Bush” zine) makes it clear that the welcoming decor isn’t just for show—hanging out is indeed encouraged. An adjacent room is dedicated to buzzy rock band the Linda Lindas (ages 14–20), who might be called Emily’s Sassy Lime’s successors. Music video props, poster art, and even custom suits designed by the girls drive home the craft required to bring their DIY ethos to life. The transition between these two immersive spaces is as seamless as the flow of time itself.

Joey Terrill, City Map 2 (detail), 1969–ongoing. Courtesy of the artist, Ortuzar Projects, New York, and Marc Selwyn Fine Arts, Beverly Hills.

A musical icon of an entirely different ilk looks on from another corner of the gallery—Britney Spears, who once declared herself “not a girl, not yet a woman.” Beneath the brush of painter Alison Van Pelt, she slips between clarity and abstraction. This marks the beginning of “Piece of Me,” a mini-exhibition assembled from the OCMA’s collection by the inaugural cohort of Orange County Young Curators. The cohort’s selections, paired with exhibition text that draws astute parallels between chosen works and the teenage experience, are illuminating. Yet, what’s most exciting about this aspect of the Biennial is the mere fact that it exists.

All too often, artistically inclined youths are pushed to produce work without any formal directive to devote themselves to appreciation. Spears’ Piece of Me eventually leads into a presentation of impressionist paintings from the Gardena High School Art Collection (a remarkable archive curated by the student body since 1919). Idyllic landscapes such as Elmer Wachtel’s The Santa Barbara Coast seem like a world away from the gritty realism of the other works—and yet the same trees have stood tall throughout all of the artists’ darkest days. Don’t worry, kids, they seem to say, even as the tides ebb and flow, California’s shores will continue to gleam.