While many of the contemporary art world’s basic assumptions have been challenged in recent years, one that has remained remarkably constant since at least the 1960s is the collective verdict on appropriation: It’s fine! Andy did it, so it must be—and too many foundationally (and financially) important artists—from Roy Lichtenstein to Barbara Kruger and Sherrie Levine—built their entire careers on pieces whose visual impact derives largely from the power of images made by other artists.

It’s safe to say that the current art world could barely exist if it hadn’t been decided long ago that changing the context of someone else’s image determines an important part of whatever it is that the fine-art viewer is supposed to care about. As the recent verdicts against Richard Prince show, the legal situation hasn’t changed in decades either—the right of an artist to avoid being appropriated by another artist still entirely depends on whether the appropriated can afford to sue the appropriator, and if a judge decides that the second work is “sufficiently transformative.” Fighting back succeeded in the case of photographers Donald Graham and Eric McNatt (appropriated by Prince), although it took almost ten years and untold legal fees. Many other photographers appropriated by Prince haven’t yet decided to gamble the thousands of dollars and years out of their lives necessary to find out if they’ll have the same luck.

However, the tables may be turning. Not only is the art world increasingly willing to recognize the consanguinity of art made by fine and commercial artists (KAWS and his Hypebeastable kin being perhaps Exhibit A) but artists operating outside the gallery system have proved to be increasingly capable of developing devoted and sincere followings despite having sources of income outside the sale of unique objects in white rooms—followings they are willing to leverage to avoid being treated as one more daisy for pop art flâneurs to pick out of the cultural landscape.

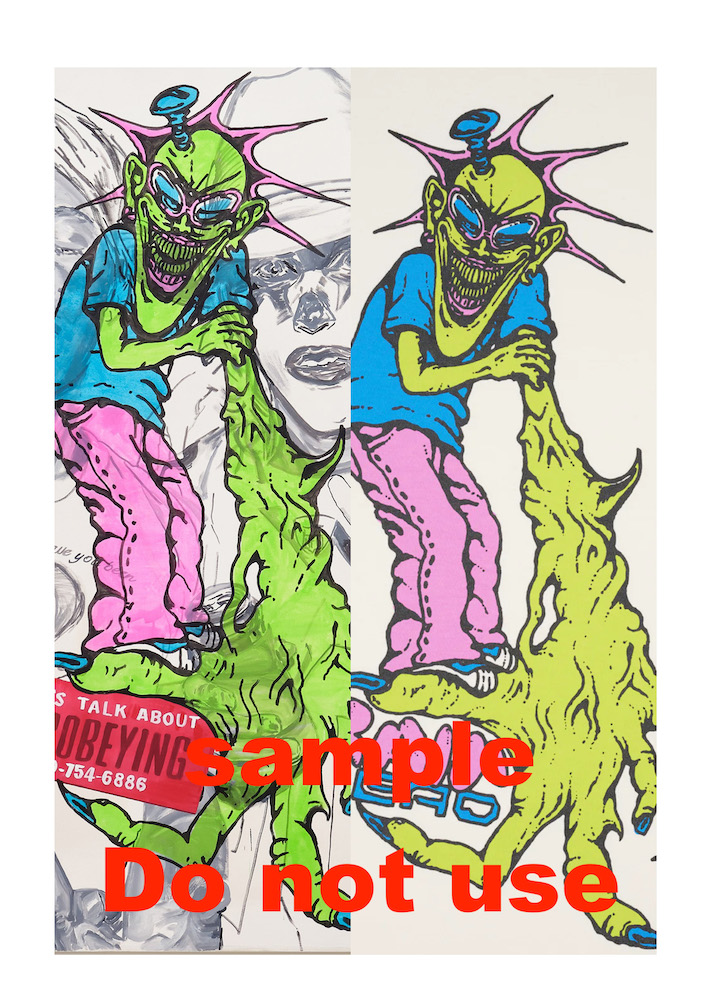

Recently, a work by neo-pop painter Gabriel Madan prominently featuring Gage Lindsten’s “Screwhead” design was shown at Gattopardo in Glendale. Although the painting consists of multiple layered images, it would be difficult to ignore that most of what the viewer sees was originally designed by another artist. It would also be difficult to ignore that Lindsten—who works in a style that updates classic fantasy, comic, psychedelic and skate art imagery with a dreamy, Day-Glo sheen—has about 30 times as many Instagram followers as Madan. According to documents acquired by Artillery, once Lindsten called Madan out on social media, he quickly agreed to pay Lindsten half his profits from any sale of the painting.

Do agreements like this suggest that—in an age where AI is an increasing threat to the livelihoods of the illustrators that fine artists so often shared dorm rooms with at art school—the idea of what and who is appropriatable is changing? Or perhaps this is just an example of the oldest art world laws at work — the one who controls an image is the one with the power to enforce that control?