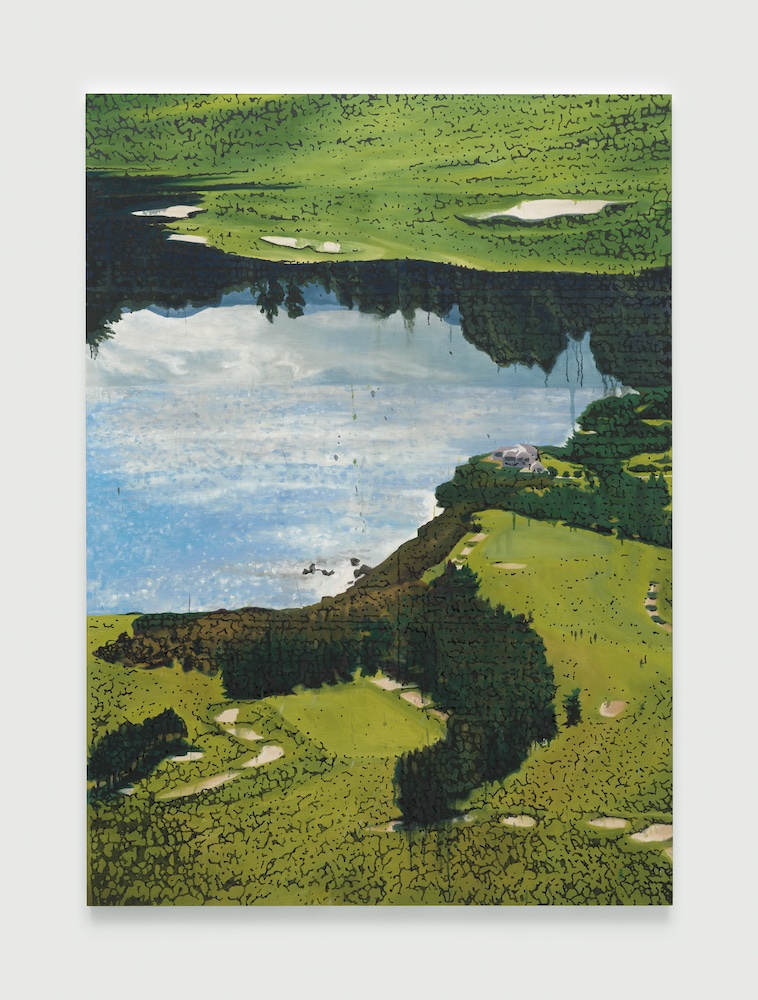

I’ll admit that before attending a press walkthrough for Nate Lowman’s “Parking” at David Zwirner a few weeks ago, I wasn’t familiar with Lowman’s oeuvre. The paintings first appeared to me thumbnail-size, attached to my iPhone invitation. I noted glowing, riparian swaths of grass-green oil paint seeking equilibrium with terraformed earth tones—visually rich abstractions with a bit of attitude. It took until I was in the space with Lowman himself (…he materialized from whatever unknowable tunnels connect the gallery’s enormous ultra-white cube campus, dressed in one black Air Force One and one white Air Force One sneaker with relaxed-fit pants and a quaff of silver hair, to speak deferentially to the corps-de-presse for half an hour, just enough to leave the impression of a mid-career aging bad boy on the raw edge of his zaddy era, before dematerializing back into the white walls…) that I even realized I was looking at abstractions of aerial views of golf courses. Lowman explained that the paintings were not landscapes but rather pictures of landscaping, and that they weren’t intended as critiques or tributes to the sport but as neutral meditations on the rising cultural supremacy of the gentleman’s game in the age of Mar-a-Lago.

I liked these paintings a lot, so I’ll get my objections out of the way before I explain what is good about them. My first objection: a rather bland bronze sculpture modeled to resemble a hollowed out snowman that is neither good nor bad nor seemingly related to the rest of the show. Also, the inclusion of a salon-style wall of other tangentially related smaller works (including a green version of his trademark oversized air-freshener tree-shaped cut-outs) that, while individually compelling, take a bit of the coldness out of the show’s curation. That salon wall feels like an acoustic guitar interlude in a show that is otherwise pretty techno, and coldness suits these paintings better. My third objection is not to the show itself but to an experience that kept happening to me after the show, where I’d mention to various art world denizens that I really liked this Nate Lowman show and I got the impression that I’d violated some kind of art world decorum. Um, everyone seemed to be saying, don’t you know that we don’t like that sort of thing right now? I pried deeper and learned that that sort of thing meant the ghosts of 2005 Lower East Side Manhattan, where an artist might do cocaine with Dash Snow and Ryan McGinley and one of the Olsen twins, back when irony was king and lads were cool and the art market was booming. I have nothing to say about this except that I believe we should release artists from the shackles of whatever they were doing in their twenties.

Despite Lowman’s insistence that his paintings aren’t landscapes, they play into a history of landscape painting and the form’s intrinsic questions of perspective. Aerial images are melded, flipped, painted sideways, enough to destroy the one-to-one feeling of the images as data. Lowman renders sandpits as floating craters defined by shadows that visually push them at once forward and backward, optical trickery that destroys any allegiance to foreground, middle ground, and background. We are left with weird physics, an inside-out golf course that looks like what the world feels like—at the beginning of an impossible future and end of an unspeakable past. As for the subject of golf: I had my doubts. Are giant paintings of golf courses merely the easiest paintings in the world to sell, since it seems inevitable that a large percentage of blue-chip art collectors might also be the type to tee off? But while I write this, the front page image of The New York Times is an aerial image of the golf course, a visual explainer for a recent act of failed political violence. I see a green river and a black pond, a blankness of sand. I see it from the POV of Nate Lowman, thank god.