Melancholy rendered in pools of soft, golden sunlight. Love and loss braided into fields of wildflowers. In the press release for “Passage,” Coco Young’s first solo show at Night Gallery, curator Martha Kirszenbaum compares the exhibition to Agnès Varda’s lush New Wave film Le Bonheur (Happiness) (1965). Numerous scenes in the doomed filmic love-ballad feature flowers shown in bloom or cut down and presented as bouquets, reminding the audience that they are present both in times of love and death.

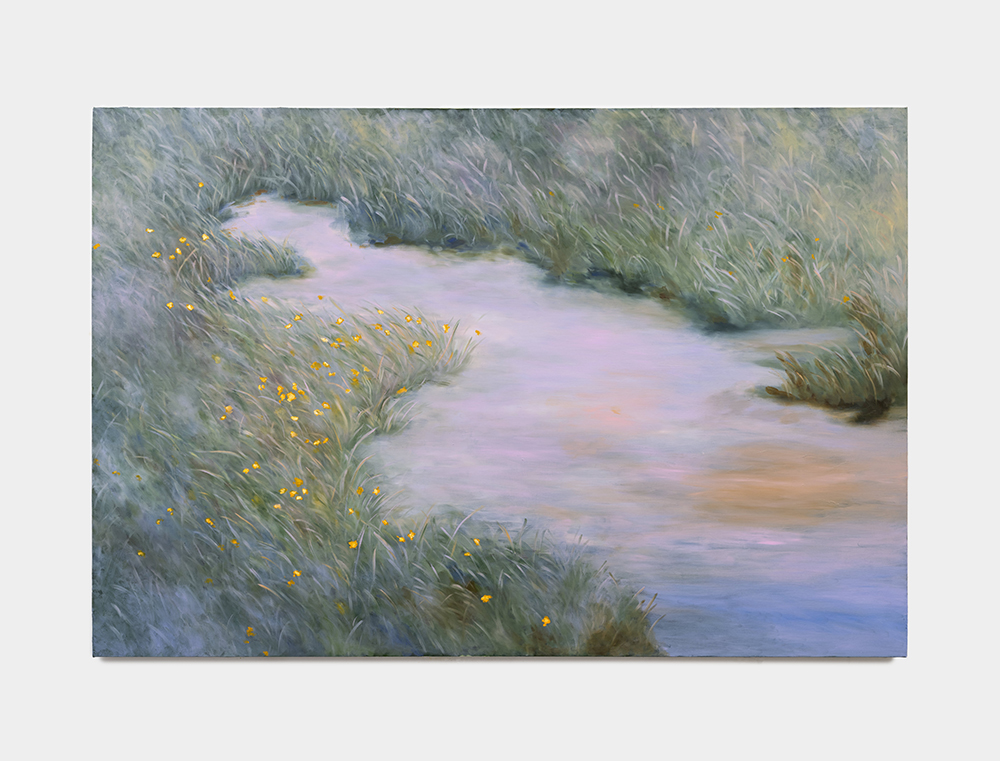

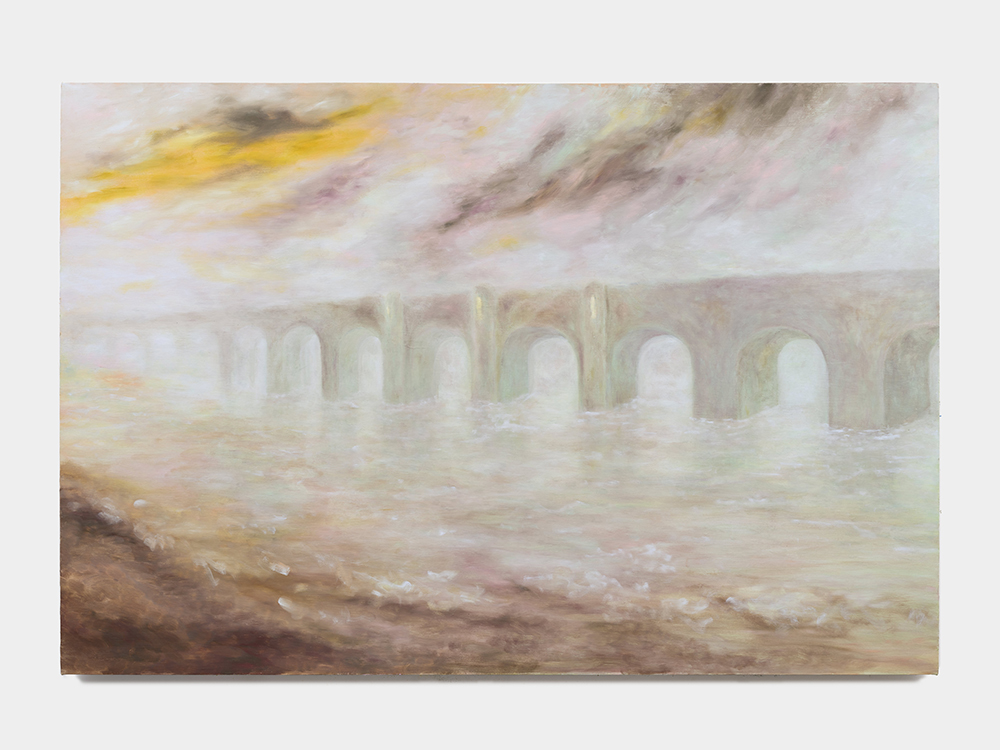

Young’s ethereal oil paintings—misty fields of yellow, blush and ivory—are similarly romantic, nostalgically steeped in reminiscences of her childhood in the sun-drenched south of France, in which she immerses her viewer. Looking at her painting Bog at Dawn (all works 2024), I feel simultaneously tucked into the soft, tangled fallow captured in the early morning’s glinting sunlight, as well as fully awake with the restlessness of youth. In Le grand ruisseau, lost in an emerald meadow freckled with delicate scarlet bossoms, the artist leads me along the banks of a meandering river, the stillness of the afternoon shown in its reflection. In The Pond, which depicts a herd of red-tinted swans, possibly stained by blood or reflecting the warm light of daybreak, I am reminded of the Greek myth Leda and the Swan, in which Zeus transforms himself into a swan to seduce a naïve Leda in a perverse act of deception. Meanwhile, the sole human figure in the exhibition appeared in Yasmin, whose subject reclines idle and patient in another idyllic pasture. Flecks of gold and peach suggest that it is spring, but the girl’s expression is difficult to read. In many of Young’s paintings I find this duality and am seduced.

Coco Young, Passage, 2024. Credit: Zashan Ahmed. Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles.

Kirszenbaum writes that the show’s title refers “to a possible transition from one world to another: childhood to adolescence, life to death.” Yet it feels insufficient to compartmentalize the existential fleetingness that Young portrays in this work. She reminds us that the wrenching, awkward transience of youth is not at odds with one’s life but rather crucial to its development; that we remain in a state of constant transition.

What Young delineates is the impact of what her childhood might have been like. Her impenetrable nostalgia, the core of our shared sensation, the spark in our internal quiet dramas we so dearly miss. With her urgent yet gentle hand, Young captures the sense that our interior selves are as turbulent as the storm clouds over the show’s titular river. The exhibition creates a haze of an eternal spring and honeysuckles, reminding us that nothing will ever be this sweet again.