Imagine, for a moment, that Izumi Kato’s figurative subjects have a life of their own. From the artist’s studio in Tokyo, his subjects have traversed the ocean, crossing the Pacific to emerge in Los Angeles. Making their way to Pico Boulevard, they appear utterly at home in Southern California—a place where one can encounter the extremes of both prehistoric geology and urban modernity, where tar pits coexist with gleaming new buildings, where eternal ocean cliffs abut concrete highway. These binaries of ancient and modern, geological and man-made, are dualities that also coexist in Kato’s work, making his exhibition a fitting choice for Perrotin’s inaugural exhibition in Los Angeles.

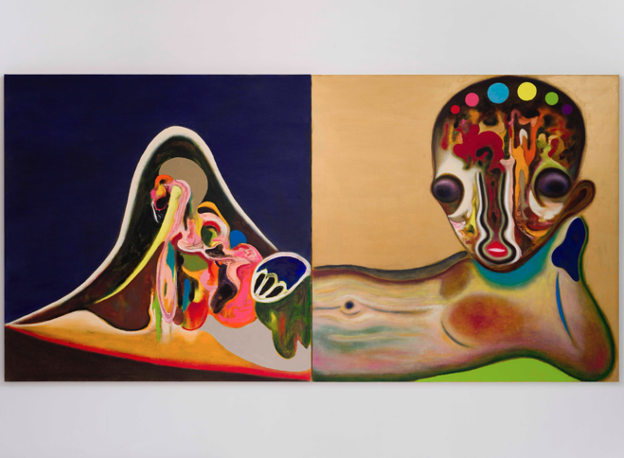

Both primitive and pop, the simple geometries and biomorphic shapes Kato uses to compose his distinctive figures seem to nod at the elemental forms found in petroglyphs and cave paintings, while also channeling the character-driven aesthetic of contemporary culture. He uses timeless natural materials such as wood and stone alongside manufactured creations such as plastic and vinyl. And Kato employs the most primal of tools—his own hands—to paint his canvases, while simultaneously experimenting with forms of production that only modern technology can enable. His not-quite-human figures could just as easily be apparitions from the future as conjured spirits from the past.

In Los Angeles, visitors to Perrotin are met by the artist’s recent figurative creations. On first encounter, their protruding round eyes and unsmiling mouths might appear to be menacing, but the more time one spends with Kato’s figures, the more one can perceive that he imbues his subjects with a stoic tenderness. Like the main character in Guillermo del Toro’s Shape of Water, Kato’s subjects, in their almost-human form, compel us to identify with them despite their strangeness.

Although trained as a painter, Kato works across media, and his exhibition in Los Angeles features both paintings and sculptures, the latter constructed from materials including stone, cast aluminum, and fabric. A monumental fabric figure, measuring over 14 feet (4.3 meters) tall, hovers above the exhibition, hanging from the soaring bow truss of Perrotin’s spacious gallery. At the opposite end of the size spectrum is a plastic model kit, an edition inspired by the artist’s own memories of toy models. On view and also available for sale, these model kits provide owners with the materials to create their own plastic miniature versions of Kato’s stone sculptures.

Born in 1969, Kato grew up in the Shimane Prefecture, an area of Japan where the Shinto god Ōkuninushi was believed to have lived. As other art critics have noted, the experience of growing up with the surrounding context of Shinto shrines and the natural landscape of mountains and sea may have implicitly informed the role of mythology and nature in Kato’s work. Though he pursued formal art education at Musashino Art University in Tokyo, Kato’s specific techniques and artistic vocabulary cannot be traced back to academic art training, but are rather the products of the artist’s self-taught and unique approach to technique and materials. Kato’s intuitive practice is especially notable for his skill as a colorist and the compelling palettes he develops for each painting.

Los Angeles is regularly cited as having the largest population of Japanese nationals outside of Japan, as well as being home to the second-largest number of Japanese-Americans living in a major metropolitan area in the United States (surpassed only by Honolulu, Hawaii). Perrotin’s presentation of Kato to inaugurate its Los Angeles space represents the first of many future ocean crossings to celebrate artistic dialogues across the Pacific.