Shulamit Nazarian is pleased to announce the opening of An Egg in Your Shoe, the gallery’s first solo exhibition by UK-based painter Dickon Drury. The artist’s thematically rich, meticulously detailed paintings mine diverse corners of art history and the genre of still-life painting to delve into themes of self-sufficiency, preservation, and regeneration with tenderness and humor.

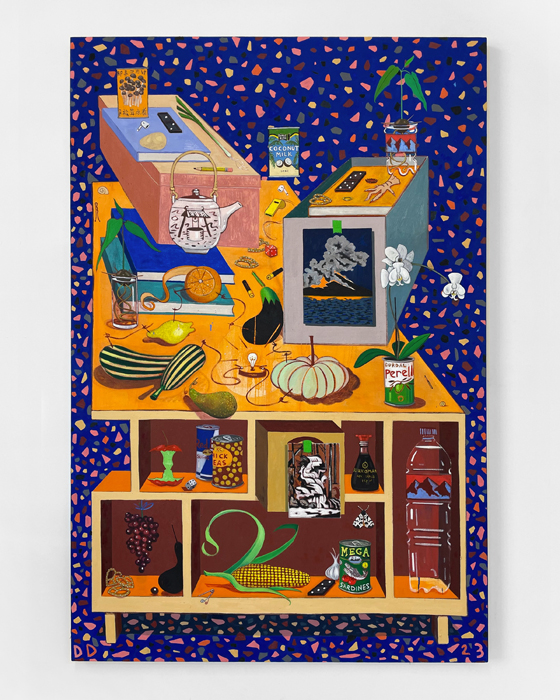

Drury’s latest series of oil paintings on linen invites viewers to contemplate the complex relationship between material possessions and a sense of home amid an uncertain future. The still lives present collections of objects that work like visual puzzles, prodding the viewer to piece together clues about the mysterious inhabitants of these scenes. Drury’s practice seeks the humor and idiosyncrasy embodied in our selection of material possessions, and his research has often looked to the supplies collected by apocalypse preppers. Boxes in the process of being packed or unpacked evoke a sense of urgency and an impending move, while rolls of bubble wrap allude to themes of protection and value for one’s beloved objects. The compositions present their diverse groupings of objects democratically, without a hierarchical division between a whistle, a lighter, or a high-end ceramic vase. Without a human figure in sight, Drury’s paintings offer an imaginative narrative played out in the background by the invisible, implicit inhabitants of his eccentric world.

The title of the exhibition references the whimsical threat, “Put an egg in your shoe and beat it.” This absurdist declaration also poses the question, how might it actually feel to walk with an egg in your shoe? An off-kilter sense of space and a diffuse feeling of disorientation pervade the tablescapes and bookshelves of Drury’s works, which he depicts as if viewed from many angles at once. The punning title also alludes to the objects and shapes that suggest multiple meanings in Drury’s compositions. In another sense, we might think of the many “easter eggs” that appear to discerning viewers of these paintings, such as cleverly rendered art historical references, hidden optical illusions, and tongue-in-cheek visual jokes.

This exhibition marks the artist’s first body of work created in his new studio in Cornwall, a coastal, Southwestern county in England, where a tidal creek flows just beyond his windows. The gentle, reflected light has softened the artist’s saturated color palette somewhat and infused many of the works with rich blues. Drury’s watery surroundings, as well as his interest in analogous forms and referential images, are emblematized in the painting A River Ain’t Too Much to Love. Here, the roaring water depicted in a perfect miniature reproduction of early twentieth-century artist Marsden Hartley’s Smelt Brook Falls echoes across an array of plastic water bottles, tinned fish, and ocean scenes on product packaging. The upper portion of the painting depicts a ceramic teapot inspired by the classic British potter Bernard Leach adorned with the image of a well. For Drury, the well motif is symbolic of the processes of introspection and gathering inspiration, but also signifies hopes for self-sufficiency as our climate crisis causes freshwater levels to drop across the globe.

Throughout Drury’s recent paintings, the eclectic throng of objects—from packaged foods and condiments, to solitary earbuds, seashells, and snails, to first aid supplies and batteries made from fruit—is suggestive of our sense of precarity in a world colored by global pandemics, political instability, and environmental catastrophe. Snails became a prominent motif in Drury’s work during lockdown as a signifier of our collective retreat into the safety of our shells. Another pervasive image throughout the works is a slender apple core, which, on closer inspection, reveals two faces shaped by the fruit’s negative space. The apple core is inspired by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin’s classic optical illusion, known as the “Rubin Vase,” in which an image of a vase that produces two faces confuses our perception of figure-ground relations. The ambiguous relationship between figure and ground embedded in the apple speaks to the larger sense of personality evoked by these scenes of strangely evocative objects. In a world in which we are confined to our domestic spaces more and more, perhaps our sense of self begins to blur with the contents of our homes, and still lives become portraits.